By Anne W. Semmes

People with especial passions and professions often travel great distances to pursue those passions. My wildlife photography daughter, Melissa Groo travels from continent to continent in her work and is presently in Patagonia, Chile teaching others how to photograph wild pumas at close range. But last week courtesy of the Bruce Museum, I was transported into deep space by five astrophotographers in its webinar, “The Art of Place in Space.”

In order to capture with their camera their stunning images, these astrophotographers must seek dark nights, that can take them from continent to continent. Just how the five panelists with their “wildly different backgrounds” gravitated to astrophotography was facilitated by Leonard Jacobs, the co-producer of Bruce Presents.

“I am Wally Krause, and I am based out of Chicago,” the first panelist began, “So, we’re going to talk tonight about looking at the great wonders of the deep sky of which we have none in Chicago. So, you’re lucky if you can see the moon and maybe Jupiter or Saturn – everything is obliterated here.” So, to find darker skies Krause, who calls himself a “backyard astronomer” and his fellow enthusiasts must drive “many miles away and in some cases halfway across the United States.” But Krause lucked out with his first astrophotography experience. “I was camping in Wisconsin under darker skies,” he told, “and I took my camera and laid it on its back on a camping chair… and pointed the lens straight up. And I set the timer for 30 seconds and I’ll see what happens.” And there he shares his photo of “the Milky Way straight up from Wisconsin.”

Krause has now spent half a century learning how to use cameras and build his own telescopes and is adept at educating others. Another image he shared of daughter Laura’s taken in California’s Pinnacles Park shows how she had “stitched together” her photos of the Milly Way in one lovely rainbow image.

Next up was the striking looking Monika Deviat, based in Alberta, Canada, who is a prize-winning photographer of distinctive nightscapes. She’s lucky to have “a lot of dark sky areas” but she walks the extra mile to “shoot the night sky from a summit.” Hence her images are especially striking. A “self-taught photographer” who studied physics at university, she shared her enterprising story of having learned of someone in her area taking photos of the Milky Way, contacting him and off they went on “a logging road in the middle of nowhere,” she tells, with her debut there of photographing the Milky Way. Her video with music showed her colorful and evocative nightscapes captured on her often-solo adventures in the Canadian Rockies.

Swiss-based, half English, half Lebanese Ben Barca’s extraordinary story started only four and a half years ago. “I had no experience with photography, and also none of the night sky,” he told. Stepping outside with his wife on “rather dark evenings” the two began stargazing. “We started to notice the meteor showers.

And I said to my wife, I’d like to take pictures of the stars.” A crazy idea she thought. But his research would bring into view just over two years ago the famous Comet Neowise. “I went out a four-minute walk and took a picture of my wife standing on a hill pointing towards the Comet.” His career then took off leading workshops and photography tours “all over the Middle East,” and winning various awards, including Milky Way Photographer of the Year two years in a row, and on the shortlist for Photographer of the Year by the Royal Observatory, Greenwich in London. He found his purpose in life. “There’s nothing more I love to do than going out and shooting the night sky.”

Architect László Francsics is based not far from Switzerland, in Budapest, Hungary. “It’s very highly polluted area,” he told. “It’s not good for us.” But he is now an internationally renowned astrophotographer and chairs the Hungarian Astrophotographers Association. He enjoys organizing photography exhibitions and choosing the best photos for them. He listed the why’s that astrophotography “is one of the best hobbies in the world. You can experience the space and time dimensions of the cosmos. The cosmos is huge, and it is changing very slowly… We can experience these huge galactic scales through astrophotography. There are much bigger telescopes and much sharper views, but with this small 8-inch small camera – a Canon 350, it can give you this beautiful view of the Andromeda Galaxy. You can capture millions of stars in the Milky Way.”

Last up was Adam Block, who developed the public observing programs at Kitt Peak National Observatory and founded the Mount Lemmon SkyCenter at the University of Arizona.

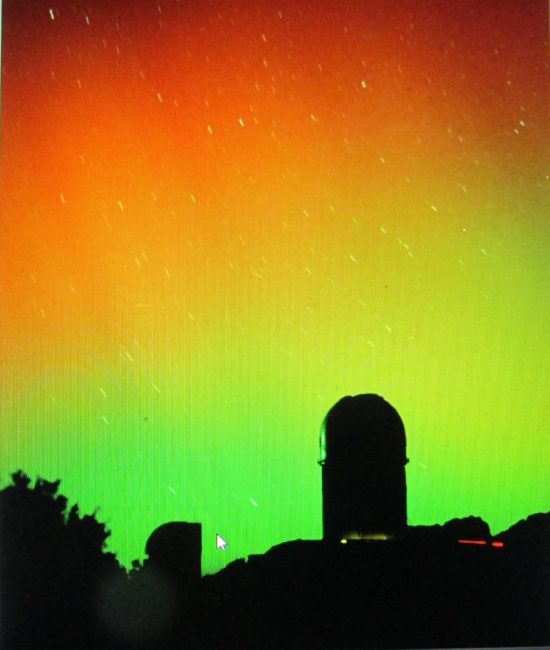

He has discovered asteroids, a supernova, and a galactic star stream. He wanted to show what he called “one of the rarest pictures of an aurora that you can see,” taken in Arizona back in 2001.

“The sun was just so active that you had this tremendous aurora, and I don’t think it’s ever happened since. There was a 20-minute display, and I didn’t have digital cameras at the time, and so I had my film camera and a tripod. I was able to capture an aurora at the Kitt Peak National Observatory.” What’s at the heart of astrophotography he shared “is in the sense that sometimes serendipity and ultimately wanting to just pay attention to the sky can be rewarding. That’s part of it for me.”

To conclude, the cameras need to be refocused on the gifted personnel at the Bruce Museum who are making news with their discoveries that did not entail long distance travel, nor needing dark skies, but merely great skill in the science of paleontology. Curator of Science Dr. Daniel Ksepka and Curatorial Kate Dzikiewicz have identified a new species of extinct bird, with its new name, Centuriavis lioae.

“It is one of the most gorgeous fossils I’ve ever seen,” told Ksepka. “So perfectly preserved. They are often crushed. But this is the entire front half of the bird, its wing bones, skull, vertebrae, shoulder bones. It lived 11 million years ago in Nebraska.”

Ksepka and Dzikiewicz, who addressed this discovery a few weeks ago on another Bruce Museum webinar on Paleontology, admitted having sat with that bird fossil for years without figuring out that it was a relative of a turkey and a grouse. “The fossil was discovered in 1933,” told Ksepka, “then sat in a museum collection for over half a century.” He came across it in 2009 in the American Museum of Natural History, took it out on loan for 10 years, then loaned it to his colleague Kate who studied it a couple of years before he retrieved it. “It took a really long time to figure out the skeletal features,” he said, adding, “It’s a study we are both very proud of.”

Another Bruce Museum colleague COO Suzanne Lio is also especially proud, for the bird has been named after her. “It’s so nice,” said Ksepka, “to name a fossil for someone in recognition of what they’ve done for you, for the Museum, and for science itself.”