By Jim Knox

With the possible exception of the Atlantic Cod, there is no other animal more closely tied to our colonial past than the wild turkey. While “fowl” was certainly served in 1621 at the three-day autumn feast that marked a successful harvest for the Plymouth Colony, those “fowl” could have been any number of bird species including ducks, geese, swans, or even the now-extinct passenger pigeon. This feast — the predecessor of modern Thanksgiving — also likely included: clams, mussels, eels, venison, corn, and even lobster. Yet, within that calendar year, Governor William Bradford’s journals speak of the great abundance, table value, and palatability of the wild turkey. In fact, the turkey became so popular with the colonists that the colony’s leaders recognized the need for conservation measures for the bird within five years of the colony’s founding.

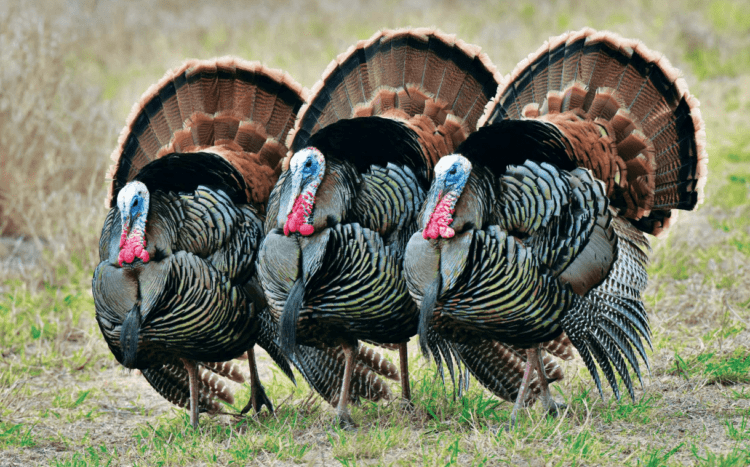

The wild turkey (meleagris gallopavo) is some bird! With a four-foot length, wingspan up to five feet, and weight of up to 24 pounds, it impresses. Boasting a powder blue head, scarlet wattle, a long, silky feather “beard,” iridescent feathers of copper, green, and mahogany, and an eye-catching tail fan, the males, or toms, are boldly marked. The females, or hens, are only slightly less colorful and smaller, adaptations to avoid detection while incubating their nests. These ground-dwelling birds are amazingly adaptable creatures represented by five subspecies throughout the United States, southern Canada, and Mexico. A native of forests, scrubland, grasslands, and swamps, the wild turkey thrives in a variety of habitats and climates. A true omnivore, the swift and sharp-eyed wild turkey subsists extremely well on what the land affords. Nearly any small living thing that grows or crawls frequently ends up on the menu. Preferred food items include grasses, seeds, bulbs, buds, stems, nuts, fruit, tubers, cacti, insects, worms, amphibians, lizards, fish, and even snakes.

A gregarious bird, the wild turkey’s success hinges upon that of its social structure, the flock. Fanning out and stalking the forest floor like a pack of velociraptors, the flock forages for plant matter and hunts for any small creature they can gobble down (you didn’t think I was going to pass on that one). This highly effective foraging behavior ensures that the collective keen eyes of the flock, mounted on the sides of the bird’s head for an astounding 270-degree field of vision, miss few opportunities for prey. This also amounts to a great defense. Many eyes can detect the slightest movement of a crouching bobcat or a leaping coyote, while acute hearing — which can detect the sound of a hunter drawing a bow — serves the flock well. When danger is detected, the birds issue a putt, or alarm call, and run at 25 miles per hour, take flight to the safety of the nearest tree, or fly cross country at 50 miles per hour.

The chicks hatch with black-spotted buff, tan, and cream plumage — highly effective camouflage for their life along the forest floor — while the ever-vigilant adult members of the f lock scan their environs for predators.

Should the mast (nut) production of the forest dip in a given year, these remarkably adaptable creatures simply shift gears to focus on other food items. As predators, these birds provide a restorative equilibrium to the landscape. (Juvenile turkeys, or poults, eat up to 76% of their diet in insect protein). Their seed dispersal properties are equally essential. Wild turkeys are known to disperse — and fertilize — more than 100 native species of grasses, fruit and nut trees!

They are indeed creatures worthy of environmental praise, yet they also impressed our founding fathers. It is true that Benjamin Franklin praised the wild turkey for its qualities, worthy of consideration as our national symbol. He asserted that the wild turkey would, “… not hesitate to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his farm yard with a red coat on.”

In 1784, Mr. Franklin went on to describe the bird in a letter to his daughter, Sarah: “In truth, the turkey is in comparison [to the eagle] a much more respectable bird, and withal a true original native of America. Eagles have been found in all countries, but the turkey was peculiar to ours.”

Additionally praised by laypeople for its good hunting and good eating qualities, the bird’s demand exceeded its population. As nonmigratory, flock-roosting birds, turkeys became big targets with an everhungry and eager market. Unfortunately, the bird’s popularity among hunters and other citizens led to its decline throughout North America. From a population estimated at 1.3 million birds, Eastern wild turkey numbers dropped precipitously to a low of just thirty thousand birds by the late 1930’s — a number smaller than current populations of endangered Polar bears, Orangutans and Asian elephants. In fact, the birds were hardest hit at the epicenter of colonial America’s expansion, with them being hunted to extinction in Connecticut in 1813 and Massachusetts by 1851.

While many admire the turkey for its pluck, I admire it for its resilience. It is a poster species for robust recovery through conservation. Due in large part to the PittmanRobertson Act of 1937, which put a tax on sporting arms and ammunition that funded wildlife conservation efforts, the birds began to slowly yet inexorably rebound.

Learning from the successes of our New England neighbors in Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire, Connecticut released 356 birds at 18 sites statewide between 1975 and 1992. Today, every one of Connecticut’s 169 towns and cities has a flock of wild turkeys. I have observed them in parks in Hartford, neighborhoods in Bridgeport, and along the I-95 corridor in New Haven.

Nationwide, we have seen the turkey’s numbers swell. In fact, it is one of the very few species which has, with rigorous protection, surpassed its pre-Colonial population numbers. Today, an estimated seven million birds inhabit 715 million of 720 million acres of suitable habitat throughout North America.

To me, the Wild turkey provides living proof that conservation can, and does, work. When we protect a species, we protect far more than a single creature or its population. We are protecting the land, its waters, and the wishes and rights of all citizens to enjoy the natural world.

Jim Knox serves as the Curator of Education for Connecticut’s Beardsley Zoo where he directs education and conservation efforts. A Member of The Explorers Club, Jim enjoys sharing his passion for wildlife with audiences in Connecticut and beyond.