By: Anne W. Semmes

These days the ability to walk outside, inhale fresh sea air, and view spectacular waterfront scenery is treasured more than ever. A special gem in Greenwich which enables us to enjoy these experiences is the Cos Cob Park. In this blog, adapted from a 1989 Oral History Project interview of Gertrude O’Donnell Riska, we explore the history of this site, originally the Cos Cob Power Plant, and the contributions of Riska’s father, Lewis Grant O’Donnell, who played an instrumental role in that history.

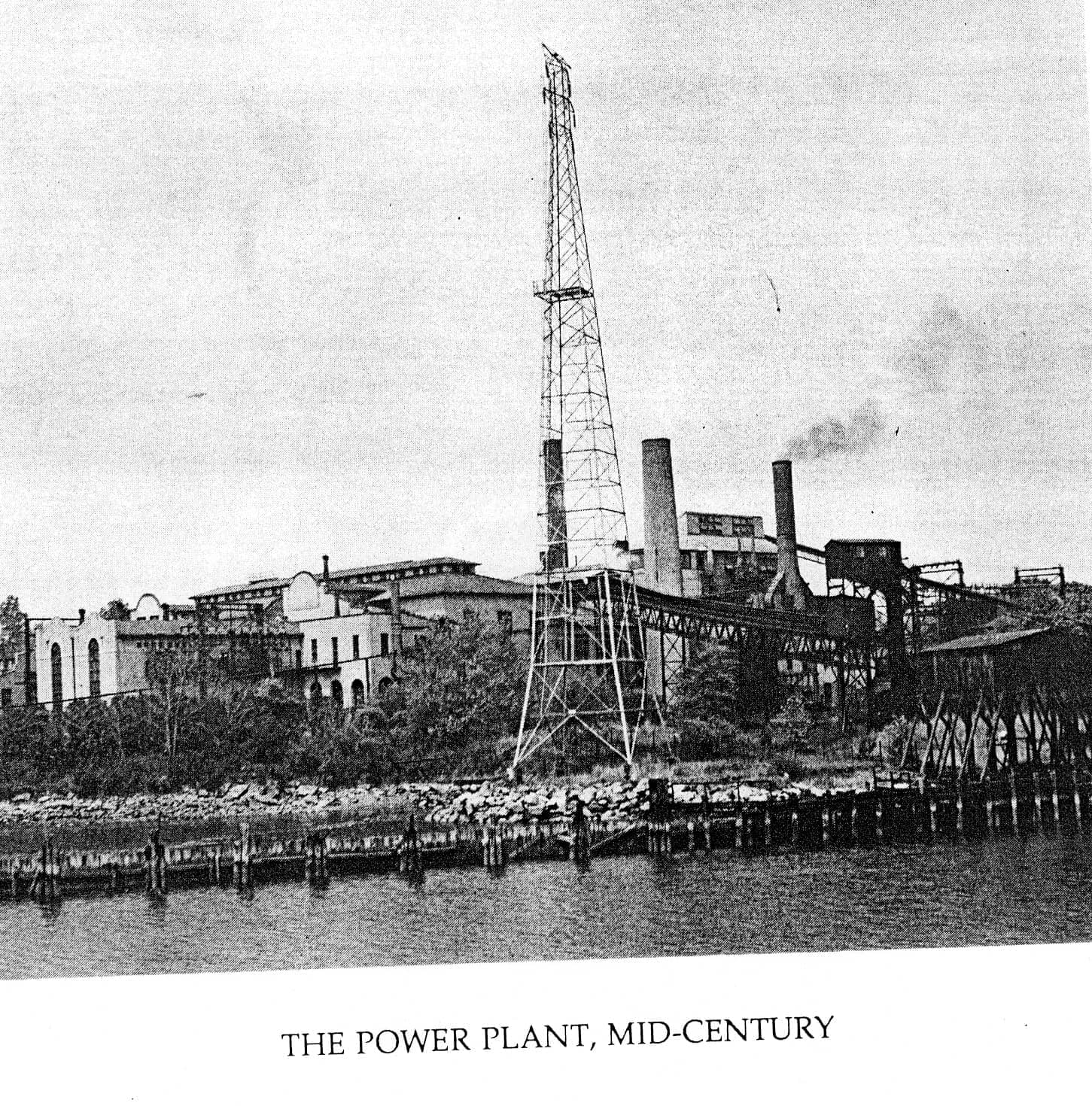

It is hard to believe that the scenic Cos Cob Park of today was once the site of the Cos Cob Power Plant, which opened in 1906 The plant was considered an engineering achievement in its day for its use of high-voltage alternating current for railroad electrification, powering trains from Long Island to New Haven. One hundred and fifty men, working round-the-clock, staffed it.

Lewis Grant O’Donnell was employed at the Cos Cob Power Plant from its inception in 1906 and was promoted to Chief Electrical Engineer in 1923, a position he held until his retirement in 1940. His daughter, Gertrude O’Donnell Riska, provided many interesting details of that 34-year period in her father’s life. For him, “It was a twenty-four-hour job, whether he was there or at home.”

Riska’s descriptions of the power plant paint a vivid picture. It was built four stories down into bedrock, with six-foot thick support pillars and walls of two-foot thick reinforced concrete. The floor was four feet in depth. The turbine room was five to six stories high, with six to eight turbines, each the size of a house sitting in a row. The plant used coal-fired steam turbines. “The minute you stepped inside the plant,” Riska said, “you were engulfed in heat and noise.”

The plant was not a stranger to accidents, and after several, O’Donnell decided on a unique way to motivate his workers to be more careful. He painted a mural of a racetrack, six feet long and three feet high, and hung it above the workers’ timeclock. Each of the racehorses on the mural was moveable from the start line to the finish. According to Riska, “Each department was represented by a different racehorse, and they advanced or retreated according to their careless accidents for the month,,.The winning department got awards.” A poem above the mural read:

“Our racehorse Safety who is fast on his feet

Can beat old Carelessness whenever they meet

So give him your support—obey all the rules

By taking no chances when working with tools.”

Competition among all the departments was so intense, according to Riska, that no more accidents occurred at the plant for the duration of her dad’s tenure there.

In addition to administering to his workers’ safety, O’Donnell was concerned about their job security. During the Great Depression, he was informed that twenty of his workers needed to be laid off. O’Donnell asked his men if they were willing to take a pay cut so none would lose their jobs. Those with seniority felt that the last ones hired should be the ones fired. As Riska tells it, her father had a different strategy in mind. The next day he announced, “I have a hat in my hand which contains slips of paper with each man’s name on it. The first twenty names pulled out are the men that will be laid off.” As none of the workers wanted to chance that outcome, they all agreed to the pay cut. O’Donnell viewed his workers as family and cared deeply about the welfare of each of them.

Other events which confronted O’Donnell included the fierce Hurricane of 1938. During that storm, the tide rose so quickly and forcefully that it short-circuited the plant and flooded the lower floors. O’Donnell did not leave the plant for a week until the trains were running again. During World War II, the power station was guarded by FBI agents as there was concern that, if it were bombed, there would be no train movement in or out of New England.

O’Donnell retired as chief electrical engineer in 1940. The power station was decommissioned in 1987 and demolished in 2001. Eventually, in 2015, a nine-acre park on Cos Cob Harbor, in the making for decades, was ready to be open to the public with its walking trails, playgrounds, turf field, and picnic area. Over 150 shade and ornamental trees, 192 evergreens, and 3,400 shrubs and perennials were planted to beautify it. In September 2016, a remembrance ceremony was held at the new 9/11 memorial placed in the park.

When you visit Cos Cob Park, remember that what is now a beautiful site was once the place where trains were powered across New England. Also, think of Lewis Grant O’Donnell, a man dedicated to his job and community and to the wellbeing and safety of all those around him.

The interview of Gertrude O’Donnell Riska, “Chief of the Power Plant,” was conducted in 1989 by Sallie Walter Williams. Its transcript may be read at Greenwich Library and is available for purchase at the Oral History Project office. Mary Jacobson serves as OHP blog editor. The Oral History Project is sponsored by the Friends of the Greenwich Library. Visit the OHP website at glohistory.org