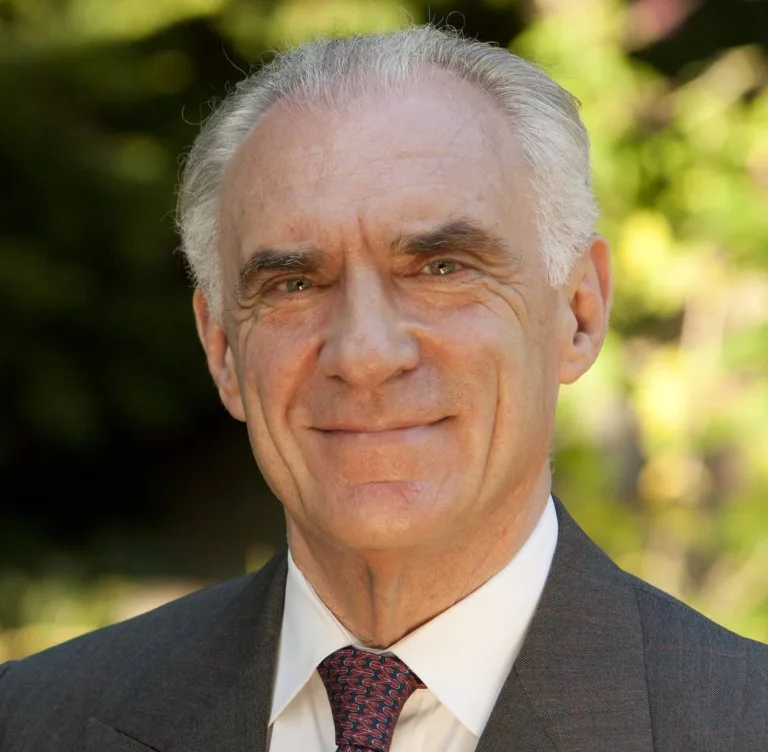

By Jim Himes

In these polarized times, it’s time to take a hard look at civility. We need to forget the idea that civility is only about manners. If manners are all that matter, we’re actually in pretty good shape. Much political lunacy is clothed in politesse and parliamentary grace. And while our President behaves in ways that many of us consider uncivil, it’s also possible to do a lot of damage with soothing tones and refined manners.

But we’re not in good shape: our politics are tribal, our beliefs have become dogma, and compromise has become a dirty word. So, it’s time to demand more of civility.

The word civil comes from the Latin civilitas—pertaining to good and orderly citizenship. If it is to be meaningful, civility must be understood as the process of thinking, debate, and compromise embraced by citizens worthy of democracy.

The challenge is that people have vastly different views on all sorts of things. I’m regularly amazed by how differently my colleagues from Seattle, rural Alabama, and suburban Phoenix view the world. Heck, people in Shelton think differently than people in Westport. We come from different places with different cultures and different values. That’s a challenge, but also a real competitive strength.

As I tell students who visit the Congress, rollicking argument produces the best ideas. You don’t want to live in a country where there is no argument: North Korea, Iran, China. So, the challenge is to make debate constructive rather than destructive; elevating rather than demeaning. That’s where civility, properly understood, is essential.

The key to real civility is understanding that no party or person possesses the absolute truth on political questions. Science may tell us precisely when the sun will rise or how much energy is in a gallon of gas, but it will never settle the big political questions that are steeped in values, ideals, and faith. How big should government be? What should it do? Who should pay for it?

Out of this one big issue comes the practical ones. How much should we regulate firearms? Who should pay how much for our highways? How much healthcare, education, and retirement security should be guaranteed?

People all over the country have their answers to those questions, but no one has the absolutely correct answers. That’s one reason why the First Amendment to our Constitution prohibits the government from controlling what you think, say, or publish.

Civility, then, must be based on the notion that how we think is sacred, not what we think. And how we think must be rooted in the humility of knowing that truth is elusive. If that is our starting point, civility then demands that we embrace dialog and debate as the process by which we arrive at shared truth, or at least, compromise. It also demands that we be willing to listen to and consider alternative ideas and, sometimes, to change ours.

This is where it gets hard. Most people think that argument is an invitation to incivility. Instead of embracing the fight, people shy from it—mustn’t discuss religion or politics in polite company. And almost everyone, for reasons that go back to our hunting and gathering days, craves certainty and is suspicious of change.

Fortunately, there are guidelines that can make this easier, which can make us truly civil, and which will improve our democracy.

First, it is the idea that matters, not the person. Nothing quells debate faster than attacking the character, motive, or experience of the person making a point. Such attacks are not only uncivil, they poison the process of seeking truth and compromise. Shouting down speakers or challenging someone’s honesty and sincerity are signs of intellectual weakness, not strength.

Second, active, critical listening is essential. I’ve noticed that in most conversations, people don’t actively listen. Instead, they are busy formulating their own response. That’s not listening. It’s not really thinking. And it stops the essential act of really considering whether there is merit in what you are hearing.

Finally, as impossible as it sounds, civility demands something counterintuitive: that we celebrate being wrong; the kind of wrong that is born of learning and a willingness to change. We must adjust our ideas in the face of better ones. It’s enormously hard to change your mind, especially for politicians, who are often accused of flip-flopping. But growth, learning, and self-improvement can only happen when our old ideas yield to new and better ideas.

This is not impossible. The scientific method and our court system rely on these principles with success. Why not our politics? We seem to use battle metaphors to describe our politics—keeping the high ground, sticking to your guns. That’s fine. But let’s make our politics a battle not to the death, but for the truth.

Jim Himes is a Greenwich resident who serves in the United States Congress in the House of Representatives for Connecticut’s fourth Congressional District.