By Tim Dumas

Contributing Editor

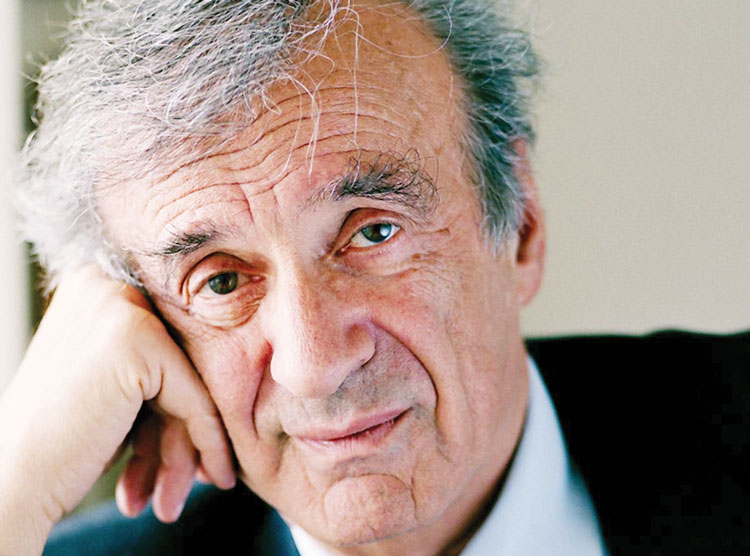

When we lived in Greenwich I would shop at the old Banksville IGA. One day, getting out of my car, I noticed an elderly couple walking across the parking lot.

They were dressed in white and had burnished white hair; they looked like spirits. I stared at the man, at his handsomely cragged face, and thought, “Can’t be.”

I followed them in. They were standing inside the entrance, gracefully dithering: Elie Wiesel, the Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate, and his wife, Marion, herself a Holocaust survivor. They turned to greet me warmly, as if they knew me. It all seemed so incongruous that I felt I should try to wake up.

The Wiesels had bought a house in Greenwich in 2004. But I didn’t know this, and so seeing them in Banksville struck me as fantastically absurd; it would have been no less strange to bump into Nelson Mandela there.

Some months later I went to a party in the neighborhood. Again the Wiesels appeared dressed in white, this time out of the dark. They told me they lived in the house next door. We chatted a little. Soon after, a signed copy of “Night” appeared in my mailbox.

I hadn’t read it before. I’d read a lot of literature about the Holocaust, from Primo Levi’s “Survival in Auschwitz” to Art Spiegelman’s “Maus,” but “Night” had eluded me, despite or perhaps because of its ubiquity.

Wiesel, who died in New York on July 2, wrote “Night” in 1955, a decade after his liberation from Buchenwald. In those first ten postwar years very little had been written about the Holocaust, as if literature had been struck dumb before a tragedy of such magnitude.

“Night” itself was too grim for most publishers to entertain. Though championed by French man of letters François Mauriac—who urged Wiesel to write it in the first place—three years passed before a small French publisher dared to bring it out, and two more before an English translation appeared here. (It was first published in Yiddish, in Buenos Aires, under the title “…And the World Was Silent.”) The book was not an overnight sensation in America or anywhere else; here, it took three years to sell out the modest first printing of 3,000 copies.

In spare prose, “Night” tells of the Nazis’ arrival in the peaceful Transylvania town of Wiesel’s birth; of his deportation by cattle car to Auschwitz and then to Buchenwald; and of trying to keep himself and his father alive through beatings, starvation, and horrors of unthinkable scale. (His father died at Buchenwald, after a beating to which 16-year-old Elie listened silently from his bunk; his mother and young sister also died in the camps. Two other sisters survived.)

I must have been about the 20 millionth reader to be bowled over by “Night.” It enters one’s consciousness less as a work of literature than as a searing document, a testament to the depravity of which humans are capable. In it there are scenes and ideas so powerful that you almost want to avert your eyes.

While we are familiar with the dehumanized Nazi oppressors, it somehow comes as a shock to “see” the dehumanization of the oppressed, reduced as they are to mere instinct; it’s as if we see the murder of their very souls. As a boy is about to be hanged, a man standing next to Wiesel says, “This ceremony, will it be over soon? I’m hungry…”

Another hanging soon follows. This time, the boy on the gallows is too light for his fallen weight to have snapped his neck, so he dangles from the rope, suffocating. “Behind me, I heard [a] man asking: ‘For God’s sake, where is God?’ And from within me I heard a voice answer: ‘Where is He? This is where—hanging here from this gallows…”

The question of God’s presence in a world where the systematic extermination of a people is possible haunts many of the 56 books—novels, memoirs, essays—that followed “Night.” There are no easy answers—but Wiesel did remain a believer.

As Wiesel’s fame grew, so did his reputation as a singular moral authority. It would have been impossible for a man burdened with that status to remain free of controversy.

He supported the Iraq War, seeing the goal of dislodging Saddam Hussein as paramount. And he frustrated those in the Israeli peace movement with his disinclination to address Palestinian suffering more forcefully. (He did speak of the Palestinians’ plight with sympathy, but assailed the leadership’s bursts of violence.)

Wiesel was not really a public presence in Greenwich.

But anyone who wandered into his orbit, even casually, could not have helped sensing the weight of history hanging about him like an aura. Having witnessed the world’s greatest inhumanity, he became among the most humane of men.