By Anne W. Semmes

Sentinel Features & Travel

The Ambassador Looks Back on the U.N., the ‘Talking Hat,’ and the Yellow Scarf

Where do you start an interview with Ambassador Joseph Verner Reed, Jr., who has served under four U.S. presidents and four secretaries-general of the United Nations, often with high-profile responsibilities? In the air, on a “huge Brazilian jet” in a party with David Rockefeller that has just brought Reed back to Greenwich from a “fabulous” 12-day trip to Morocco.

Reed, newly widowed with the loss of his wife, Mimi, of 56 years, was returning not for the first time to his former post as Ambassador to Morocco. “We traveled to Fez, with David leading the way (age 100) over the Atlas Mountains, to the city of Ouarzazate on the edge of the Sahara Desert, ending up in so beautiful Marrakech!”

And yes, said the ambassador, Morocco is a safe place to visit. “It’s a very peaceful country, well organized and well run.”

Leader Rockefeller then whisked Reed and party to Paris, where Reed’s daughter, Electra Reed, and son Vladimir joined them, courtesy of that Brazilian jet. A trip to Versailles showed the great reach of the Rockefeller generosity. “We saw there a fabulous and huge plaque dedicated to John D. Rockefeller, Jr., David’s father, in appreciation of his help in restoring and rehabilitating Versailles, the Chateaux Fontainebleau, and both Reims and Chartres Cathedrals after WWI. It was staggering.” (Both father and son David Rockefeller received France’s highest decoration in tribute, the Grand-Croix de la Legion d’honneur.

Reed’s friendship with David Rockefeller goes way back to two years after Reed’s graduation from Yale, when he was hired as vice president and assistant to the chairman of Chase Manhattan Bank (now Chase), David Rockefeller. Reed was put on the banking track at graduation time by his mentor, Yale University President Whitney Griswold, who directed him to make haste to the Washington offices of Eugene Black at the World Bank.

Griswold no doubt recognized Reed’s gracious and accommodating nature, and discreet way of dealing with people that would later be described as “Reed Diplomacy.”

So how does Reed define that “Reed Diplomacy?”

“It’s respecting others,” he said, “and paving the way gracefully toward mutual goals.”

Reed had the example of his father, Joseph Verner Reed, Sr., he said. “My father was a wonderful diplomat. He served in the American Embassy in Paris under Ambassador Amory Houghton. He had a wonderful way with people. He was a diplomat’s diplomat.”

President Reagan would recognize those Reed diplomatic skills when he posted Reed to Morocco in 1981; President George H.W. Bush did likewise in 1989, making him his chief of protocol. In that service, Reed was awarded a Legion of Honor medal from France for his tireless skill of organizing meetings between President Mitterand and President Bush—indeed, Mr. Mitterand had more meetings with Mr. Bush than with any other leader.

“Mr. Mitterrand was very appreciative,” said Reed. “It was a great honor.”

A Famous Howler

But here we pause for a little reality check—and a confession: “I was and am responsible for the worst protocol gaffe in the history of the United States,” Reed declared.

He told the Tale of the “Talking Hat” that in the spring of 1990 went round the world on the wings of the media. As President Bush’s protocol chief, he said, “I was responsible for the many parts of the visit of Queen Elizabeth to America. I accompanied her to Washington, D.C., to Texas, and to Florida. When she arrived in Washington, the president asked me to redo the arrival ceremony at the White House that had been the same since President Franklin D. Roosevelt.”

Reed was to redirect the ceremony to face the White House rather than the South Lawn and Washington Monument. “President Bush made his warm welcome to the Queen,” he said. The Queen stepped up on the platform—but something vital was missing, the kick-step for the petite Queen. “All you could see was her hat bobbing up and down behind the microphones,” said Reed, “Ever since, it’s become known as ‘the Talking Hat.’ It was a nightmare!”

Facing Armageddon afterwards with the swarm of newspaper reporters on the steps of Blair House, the calming Reed exclaimed, “I thought Her Majesty’s hat was so elegant—I wanted all of Washington and the world to see it.”

The Queen had her chance for a touché the next day when she took her historic place before a joint session of Congress—properly elevated. Holding her audience in great suspense in a pause before her address, she looked to the right then left and then to left across the assembled heads and said, “I hope all of you can see me this time.” All assembled rose to their feet in applause.

The incident would create a curious bond between the protocol chief and the British monarch. When Reed was assigned by the secretary-general of the U.N. to attend a meeting in Cyprus, he found Her Majesty also there, and was summoned to dinner. “I arrived on time on deck of the ‘Britannia,’ he said. Finding her amidst her court she suddenly pointed to Reed and said to him, ‘You should have the Talking Hat on your tombstone.’”

Reed keeps the communication going. “I just wrote to her congratulating her as the longest reigning queen and sent along a photograph of her Talking Hat.”

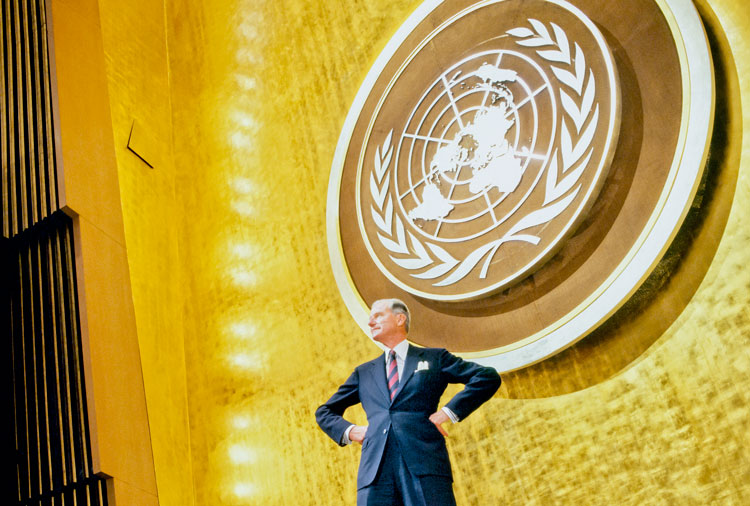

Reed is also in close touch with all four secretaries-general of the United Nations, whom he calls his personal friends—friendships formed during his 32 years serving as an under-secretary general with various titles.

“I have the most beautiful office in the building, on the 20th floor,” said Reed. “It faces west across the skyscrapers of New York.” Four years ago, he was called back to head up the U.N.’s Staff-Management Coordination Committee to deal with staff issues. “The work is very complex, negotiating over compensations between management and staff in the thousands,” he said. Now, slowing down a bit, and dealing with Parkinson’s, and turning 78 in December, he is on call three days a week.

He is unabashed over his devotion and commitment to the work of the U.N. (His license plate reads fittingly USA-UN). He has written out a testament to that effect, and he passed to this reporter. “The U.N. remains rightly an ambitious organization; as the agreement of the sustainable development goals shows. Today, the U.N. provides food to 90 million people in 80 countries, vaccinates 58 percent of the world’s children—saving three million lives a year. It assists 39 million refugees. Its peacekeeping operation alone is spectacular, with over 125,000 peacekeepers serving in 16 operations on four continents.

“But in looking back,” he ended, “We cannot lose sight of the challenges ahead; climate change, violent extremism, and other issues.”

He is astonished with the growth of the U.N. during his tenure. “There are now 193 member states,” he said. “When I started there were 140 countries. There’s been an explosion. When you think the original charter was signed in 1945 with 51 countries.”

He was proud and heartened on October 24, United Nations Day—the day the Charter is honored—when he presided as he does every year at Julian Curtiss School for its Parade of Nations. “They had 60 countries represented in their national costumes, and 40 languages,” he said. “It was spectacular.”

Reed’s Art Legacy

Within the U.N. building, he has established a most visual legacy with its renowned art collection. He began by negotiating for a portrait of Nelson Mandela that now hangs on the second floor outside the Security Council. Reed had had two memorable meetings with Mandela in the White House.

He negotiated with Nelson Rockefeller’s widow, Happy Rockefeller, for the loan of Picasso’s famous “Guernica,” which has hung outside the Security Council for the last ten years or more. With Mrs. Rockefeller’s death this year, he noted, “Happy’s estate now owns it.” Reed has secured an agreement with Nelson, Jr., to have it stay another three years. “It’s the number one piece of art in the U.N.,” he said, “which has some 200 art pieces in the collection valued over 400 million dollars.” (And yes, tours are given of the art collection.)

It was on another trip with David Rockefeller, to Oman, that perhaps the seeds were sown that would bring an entire room from that country to the U.N. They were visiting with friend, the Sultan of Oman, when the news came that Nelson Rockefeller had died. “I want to offer you my plane,” the Sultan said. “We have our own,” came the reply.

“There is also a wonderful tapestry from Belgium,” said Reed. “If you took a thread out of the tapestry it would stretch to the exact circumference of the globe.”

Reed has likely circled the globe numerous times in his diplomatic travels. Another trip with David Rockefeller made some history. “We were the first Americans traveling to China after President Nixon’s visit in 1973,” said Reed. “We didn’t find a single vehicle. Everyone was on foot or on a bicycle.”

Their mission was to reestablish the relationship with Chase Manhattan Bank and the Bank of China. “We were staying in the Grand Hotel and there were no mattresses—only ropes for bedding,” said Reed. “Suddenly, in the middle of the night, we were awoken to visit Deng Xiaoping, the premier and senior member of the government of the People’s Republic of China. Under full moonlight we passed through Tiananmen Square—no one was there. We went up to the Great Hall and there was Deng Xiaoping, standing under a spotlight.”

Reed found other reasons to travel multiple times to China. “I worked on a huge publishing project, ‘Culture and Civilization of China,’ 18 volumes, with Yale University Press, the largest university press in America. We reached across the world for our experts—for 447 consultants. There’s a book on architecture, ceramics, and philosophy. The last book was on porcelain. We finished up eight years ago. The Chinese government was so generous. They gave me their highest publishing industry award.”

But the place that stays at the top of Reed’s travel list is Peru’s Machu Picchu. “I was on a tour in 1985 for David Rockefeller to visit Chase Manhattan Bank facilities and this was an opportunity to go to Peru—and to Machu Picchu. Three of us spent the night there, Mimi and I and a bank associate, under the stars.”

“In all my travels to 140 countries,” he said, “this was the most magical, mysterious, wonderful place. How they constructed it, with such precise construction of stones, is a mystery.”

Reed would later be called on to negotiate the return to Peru of the treasures collected there by Hiram Bingham III, and long exhibited at Yale University’s Peabody Museum. “It was very difficult, but we negotiated their return, where they are now in a museum in Cuzco,” said Reed. He added, “The Yale authorities have been very generous toward my efforts whenever the subject comes up.”

Those less fortunate than Reed in their travels would include the Shah of Iran. Reed was tapped for what became “the worst job” of his life, he said, when he was asked by David Rockefeller in the fall of 1979 to arrange Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s—the Shah of Iran’s—entry into the U.S. after his fall from power. “He first went to Egypt,” said Reed, “then Morocco, then the Bahamas, and then to New York for medical treatment at New York Hospital.” Reed helped relocate the Shah to Mexico, “but the Mexicans overcharged anything and everything, so we got him to Texas, then Panama, and he finally returned to Egypt, where he died.”

Reed then stepped up for the Shah’s widow, Farah Diba, helping facilitate her move to Greenwich. “She later moved to Paris,” said Reed.

Reed the world traveler stays rooted in Greenwich. He looks back fondly on the 20 years he lived in what was his father’s Riversville Road home, Denbigh Farm, now sold to others. “It had 184 acres of land with an unbroken view, from Mount Kisco to Port Chester—with 20,000 square feet of house,” he said, shaking his head.

This reporter recalled being in his sunroom there on an interview years ago, when he was opening drawers showing beautiful botanical prints dating from the 18th and 19th centuries. That triggered his memory of when his father donated rare original folios of Audubon Prints to Deerfield Academy, the prep school that all four Reed brothers attended. “There were 435 Audubon plates,” he said, “Deerfield sold them to a bandit in Australia for $7.5 million, who recently sold them for $23 million.”

Back then, Reed had shared his trick of wearing a yellow scarf wrapped around his neck when he traveled so that when he got off the plane, his wife could immediately spot him. “Do you still wear the yellow scarf?” he was asked. “I always wore the yellow scarf so people at Chase bank could locate me, and I still do.”

Reed then pointed to a box sitting nearby. “Would you bring it to me?” he asked. “It’s from Paris, from Charvet—that famous haberdashery on the Place Vendome.”

Opening it, out came a beautiful new yellow cashmere scarf that he proceeded to wrap around his neck with a smile.