By Anne W. Semmes

The extraordinary art and of 98 years-long life of “American Modernist Georgia O’Keeffe – From Lush Flowers to the New Mexico Desert,” was spelled out in word and image last Wednesday week at the Riverside Yacht Club at the celebratory 40th anniversary of the Greenwich Decorative Arts Society, with some 110 members and guests attending. Featured speaker was Greenwich-based Janetta Rebold Benton, Distinguished Professor of Art History at Pace University.

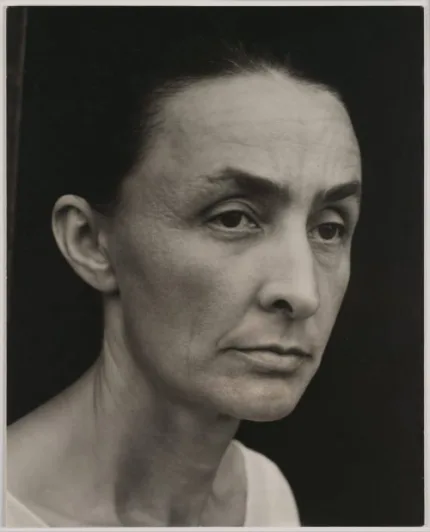

“She is a two-time Fulbright scholar,” introduced Decorative Arts President Ellen Brennan Galvin of Dr. Benton who began her share of O’Keeffe as born in 1887 in a farmhouse of seven children in Wisconsin with her parents as dairy farmers. O’Keefe was “often described as an individualist, independent, self-confident, a determined and strong-willed personality, deciding to become an artist by the time she was 10 years old.”

O’Keeffe had turned to art she wrote, “for words and I are not good friends.” “Rather than the written world,” shared Benton, “Her medium was visual. She said only abstract art permitted her to express herself.”

O’Keeffe studied art at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Art Students League in New York, the University of Virginia, and Columbia University’s Teacher College.

“Her first abstract drawings were made in 1915. Forms are modeled… to appear three dimensional and rounded. This curving shape will reoccur in her other works of art.” Those charcoal drawings would be introduced to famous photographer and New York gallery owner Alfred Steiglitz who would exhibit them in 1916, with O’Keeffe not knowing nor having met Steiglitz.

“Stieglitz was infatuated first with Georgia O’Keeffe’s art and then with Georgia O’Keeffe,” told Benton. “He invited her to move to New York. She accepted in 1918 and soon moved in with him. Stieglitz was charismatic, dynamic, energetic, and a hardworking perfectionist. She was 31, he was 54, never mind that he was 23 years her senior and married.”

But in 1916 O’Keeffe was heading up the art department of the West Texas State Normal College and had first traveled to New Mexico she would fall in love with. Stieglitz was well-educated and an “encourager of modern art by exhibiting early 20th century American and European artists.”

Stieglitz promotes O’Keeffe

Beginning in 1917, “Stieglitz is ultimately making over 350 photographs of her… Her hands were particular interest to Stieglitz, and his photos give great attention to them…Stieglitz photographed her with her paintings, without her paintings, and, without her clothes.” Benton then showed her audience that astonishing photograph of O’Keeffe fully in the nude.

“She was 31,” and with Steiglitz’s wife “returning home during one of these photography sessions, effectively ending the marriage.” But six years “passed before the divorce was final.”

Benton described some of those nude photographs as “artistic. Others, to put it delicately to this group, are more of a straightforward erotic organization.”

Those exhibits happening into 1921 Benton said, brought Stieglitz “fame or notoriety, but for O’Keeffe, this is to a great extent what the public first saw of her, not her paintings.” And “it’s worth noting that she posed for the photographs. She even helped to develop the photographs… It has been said that there is no such thing as bad publicity.”

In New York City O’Keefe would be introduced to her artist contemporaries: Arthur Dove, John Marin, Charles Demuth, and Marsden Hartley. Dove’s work brought O’Keeffe’s words, “The way you see the nature depends on whatever has influenced your way of seeing…It is Arthur Dove who affected my start, who helped me find something of my own.”

O’Keefe would paint Lake George in her New York years in 1922. And specific large scale buildings New York City caught her attention, like the “Radiator Building – Night,” in 1927, and in later years the Brooklyn Bridge.

“Each year, starting in 1923, Stieglitz gave her a solo exhibition. Her fame grew and the prices of her piece soared as she established a style of beautiful color harmonies and smooth undulating shapes that she would maintain for decades.”

“In 1924, she began the famous large paintings of large flowers,” told Benton. With these her popularity as an artist increased. She said, ‘When you take a flower in your hand and really look at it, it’s your world. For a moment, I want to give that world to someone else.” And, in 1924 Stieglitz was divorced. “O’Keeffe and Stieglitz promptly married, with John Marin as best man at the wedding.”

As to those large flower paintings, Benton described, “Usually a flower is seen close up and enlarged to the extent that approaches an abstract pattern… The colors are rich, saturated, splendid, and varied. O’Keeffe depicted flowers of many types, lovingly, accurately, although not always scientifically…. She tried to convey her experience with the flower and explained that she began very realistically, but that as she repeatedly painted the same subject, the organic imagery gradually evolved under her brush.” O’Keeffe said also she painted flowers as “they’re cheaper than models and they don’t move.”

The draw of New Mexico

O’Keeffe’s love affair with the Southwest began in 1929 on a trip to Taos, New Mexico, where she painted the Church of Saint Francis of Assisi. “She depicted this church repeatedly…

The appeal of this building comes largely from the material used…sun dried brick” with “the building’s edges soft and rounded by the repeated resurfacing and passing of time adding to its sculptural handcrafted appeal.”

Spending part of every year in New Mexico, “She hiked, she painted the scenery, including the flowers and the bones and rocks. She found nature provided her preferred subject matter. Nature’s creatures distilled their essential essence examined and then depicted in harmonious colors.” Color, said O’Keeffe, “is one of the great things in the world that makes life worth living to me.”

But in 1932 O’Keeffe would suffer a nervous breakdown, being hospitalized in New York City, recuperating in Bermuda, before returning to New Mexico. Her marriage “had become difficult and they often lived apart.” Stieglitz had “never visited her… but she wrote to him frequently.” Come 1946 Stieglitz would die of a cerebral blood clot. And “O’Keeffe would move permanently to New Mexico, from 1949 until her death in 1986.”

Living in her “Ghost House” with its 12 acres… “Electricity came from a generator. There was no telephone. Daily life was structured. Get up early, walk the dogs [two chows], eat breakfast, go out and paint all day, walk, eat, dinner, sleep, repeat. She drank chamomile tea. She listened to classical music. Her preferred form of transportation was her Model A Ford. Although she received various guests at the ranch, she is often described as a loner. She lived an isolated life there, which to her equated with freedom, preclusive by nature.” In O’Keeffe’s words – “I find people very difficult.”

But O’Keeffe would finally acquire her long wanted and abandoned hacienda in Abiquiú, which she renovated into a home and studio, and would divide her time between the two houses.

Her declining years

Then in 1974, suffering loss of vision due to macular degeneration, she found assistance from a “young, handsome, helpful potter,” Juan Hamilton. “He helped her learn to work in clay, making pottery. She returned to working in watercolor in 1976. She wrote a book about her art. In 1984, her declining health prompted her to move to Santa Fe. She was 97.”

Through those many years O’Keeffe “was able to enjoy her fame. Major exhibitions of her work were already held in the U.S. and every several years there was a major exhibition in a major museum in a major city…. She worked until she died, which was March 6, 1986… Much of her estate went to the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation and then to the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe.”

Benton ended her informative talk with, “If you share the aesthetic preferences of Georgia O’Keeffe, you might choose to go to St. Francis of Assisi in New Mexico… She depicted her two homes repeatedly. The paintings verge on abstraction in their simplicity. For Georgia O’Keeffe, a rugged, colorful, simple, natural environment was a fundamental mental health requirement.” And for Benton, she confided, “I would love to be there walking with Georgia O’Keeffe as my guide.”