Every now and then, someone leaves this world whose decency feels almost old-fashioned, as if borrowed from an earlier, kinder America.

Betsi Shays was one of those people.

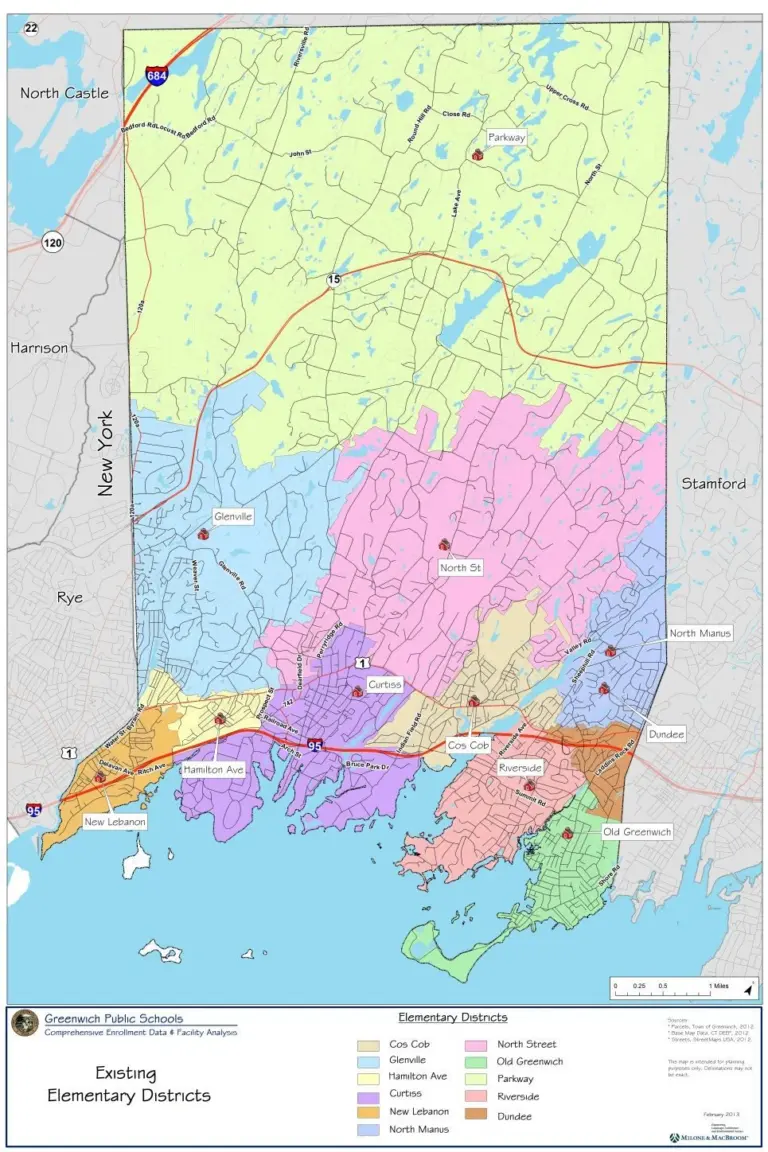

For decades in Greenwich, in New Canaan, and through the winding towns of Connecticut’s Fourth Congressional District, she stood—not in the spotlight, but just beyond it—holding things together. She had no appetite for self-display. Her gift was steadiness, gratitude, and a particular kind of kindness that asked nothing in return.

Those who worked in or around the Shays offices know the ritual well: a letter in the mail, raspberry ink, signed “betsi,” lowercase b. “Thank you for cheering us on,” it often said. Not a slogan, not a line tested by consultants, but an expression of the way she lived—believing that service was a shared act, not a solo performance.

She wrote those letters herself.

Her optimism was relentless. Maddening, sometimes. If the room was gloomy, she opened a window. If the numbers were bad, she found something good in the trying. You couldn’t be a cynic around Betsi; she made it impossible to stay that way. She believed in the good, and if she couldn’t quite see it, she looked harder. She never used another’s failure as conversation, never joined in complaint. That refusal to wound was its own quiet strength.

Betsi and Chris Shays were high-school sweethearts, Peace Corps volunteers in Fiji, partners in life and vocation. When Chris served in Congress, she became, by choice and by instinct, the connective tissue—calling, writing, listening. Her way of being said you can’t just hold an office, you have to hold people. In campaign offices and classrooms alike, that was her way.

Before politics, there was teaching—in New Canaan, where she loved her students and they loved her back. She brought the same habits there that she brought everywhere: seeing potential where others saw limits, speaking encouragement where others spoke correction. Teaching and politics aren’t so different at their best; both require faith in the human creature. Betsi had that faith in abundance.

Later, when the campaigns quieted, she continued to serve, directing educational initiatives for the Peace Corps—helping teachers connect their classrooms with the larger world. Even in that role, her ethos stayed the same: lead gently, listen first, thank often. Her life never drifted far from the basic lesson—that every person wants to be seen, and deserves to be.

What I remember: she favored Jessica McClintock perfume—soft, floral, unmistakable—and a raspberry-colored pen that left a little flourish at the end of every note. When Chris was weary, she’d smile and tell us not to worry, “He just needs a run and some Aaron Copland,” whose music could lift a spirit from discouragement to resolve. When my daughter was born we received ten children’s books and a suggestion to read them until pages were worn. That advice, well received and executed, likely helped produce the Sentinel’s own Emma Barhydt: book reviewer, writer, editor, and teacher.

After Chris left office, Betsi and Chris eventually moved to Maryland, but Betsi’s impact in Connecticut remains. The friends, the volunteers, the students, the neighbors: will remember the small gestures that came to define her. A call. A note. A prayer. A presence.

What she gave us, really, was an argument—not political, but moral. That kindness is not weakness. That optimism is not evasion. That gratitude is a force multiplier in human affairs. She lived that truth every day, and it changed the texture of the communities she touched.

The best people leave behind a tone, a way of being that quietly alters everyone who knew them. Betsi’s tone was one of grace.

And the way we honor that now is simple: pick up the pen, write the note, look for the good. Cheer someone on.

Because that’s what she did.

And she was right.