By Marek Zabriskie

In the spring of my senior year in college at Emory University, I sensed that God was calling me to become a priest. While I was raised as an Episcopalian, there was no Episcopal church within walking distance of my campus. So, for two years, I attended the Roman Catholic Church on campus.

I felt both drawn and repelled by the idea of potentially becoming a Roman Catholic priest. I felt ill-equipped, and unworthy, and I couldn’t speak in public. I wasn’t a leader, wasn’t raised in the Catholic Church, and I didn’t feel called to be celibate.

I graduated and spent nine months living in Paris and London, and eventually returned to the United States, where I worked as a journalist in Atlanta and later in Nashville. I felt called to be active as a Christian.

I attended Episcopal church each Sunday and got involved in all sorts of ministries, working with teenagers, juvenile delinquents, homeless people, prison inmates, and I served as a big brother to man recently released from prison.

Perhaps the most satisfying experience was serving in a homeless shelter, where church volunteers prepared, served, and ate meals with the homeless. As we sat shared platefuls of meatloaf, cornbread, mashed potatoes, and green beans, all of our pretentions melted away.

No one boasted of anything or tried to outdo one another. There were no fancy cars, no status clothes or accoutrements – just blue jeans, flannel shirts, boots or sneakers, smiles and words of gratitude. I felt completely accepted, welcomed, and appreciated by our guests and was grateful for our conversations.

After supper, everyone tucked in. As one of the volunteers who stayed the night, I slept in a little room with a bare lightbulb that always stayed on. It was hard to sleep, and from time to time someone got up to use the bathroom or asked for a glass of water. In the morning after everyone had departed, I headed to the newspaper feeling half dead, but fully alive inside.

I had sacrificed something to serve people in need who were struggling in life. And I never felt closer to God than in those mornings after I had stayed up much of the night to ensure that people who were down and out had a good meal and a safe, secure place to spend the night.

There is a Lutheran church in Copenhagen, where vandals broke in and caused a lot of damage. They broke off the hands of a statue of Jesus with his arms outstretched to welcome and bless.

Church members rallied to repair their church, but their leaders decided not to fix the disfigured statue of Jesus. Instead, they left it as it was and placed a sign underneath with the words of Saint Teresa of Avila:

Christ has no body but yours,

no hands, but yours,

no feet, but yours.

Yours are the eyes through which Christ’s compassion must look out on this world.

Yours are the feet with which

He is to go about doing good,

Yours are the hands with which

He is to bless us now.

That story had a profound impact upon me. It’s so graphic and so true. We are the Body of Christ – Jesus’ hands and feet. His mission was clear, and so is ours.

When Jesus entered the synagogue in Nazareth and was invited to preach, he asked them to unroll the scroll of the book Isaiah to where it read, “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” (Luke 4:17-19)

This was Jesus’ mission statement. The Bible calls us over and over again to care for those in need. We Christians haven’t always got this right. Because we are rooted in a tradition that goes back two thousand years, we can become glued to the way things have always been and use the Bible to support tradition, even if it’s at the expense of oppressing people.

For years, the Episcopal Church argued over human sexuality for which the Bible offers few statements and which Jesus never once addressed, while ignoring the Bible’s great focus on caring for the poor.

At the 2006 National Prayer Breakfast in Washington, D.C., Bono, a generous philanthropist and committed Christian who is the lead singer of the rock group U2, noted, “It’s no coincidence that in the scriptures, poverty is mentioned 2,100 times. It’s not an accident. That’s a lot of airtime – 2,100 mentions. You know, the only time Christ is judgmental is on the subject of the poor. ‘As you have done it unto the least of these my brethren, you have done it unto me.’” (Matt. 25:40)

What have you done for the least of mine? As long as there are strangers, people who are hungry, naked, and sick, prisoners, refugees, victims of human trafficking, people who are handicapped physically, mentally, or emotionally, people out of work, or without a home, or a piece of land, there will be a haunting question from God, “What have you done for the least of mine?”

Throughout the Bible there’s an enormous focus on caring for immigrants, strangers, aliens, foreigners, children, widows, orphans, the elderly, and the poor. When the Church gets this right, people respect it.

When we model this as a family, our children see it and take note. They learn that we are meant to live a sacrificial life, sharing some of our time, money, and energy to care for others. The Christian faith becomes more real to them.

There’s an old bumper sticker that read, “If you were accused of being a Christian, would there be enough evidence to convict you?” That’s one way of looking at it. Are you leading a life that is any different from that of a person who is not a believer or follower of Jesus?

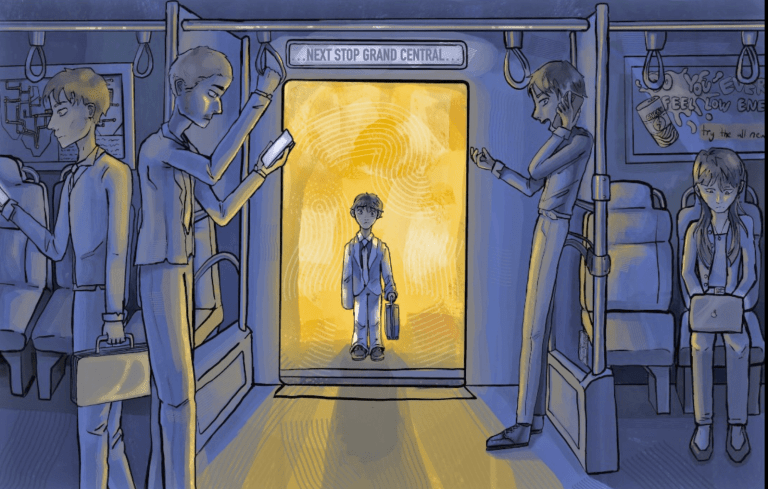

The other way to look at it is to ask, “Am I missing something vital because I have cut myself off from those who are poor and needy and in a different place in life.” We Christians believe that we meet Christ in the face of the poor, the needy, and those who struggle. We also believe that we come most spiritually alive when we connect with them. Food for thought.

The Rev. Marek P. Zabriskie is Rector of Christ Church Greenwich.