Column – On my Watch

By Anne W. Semmes

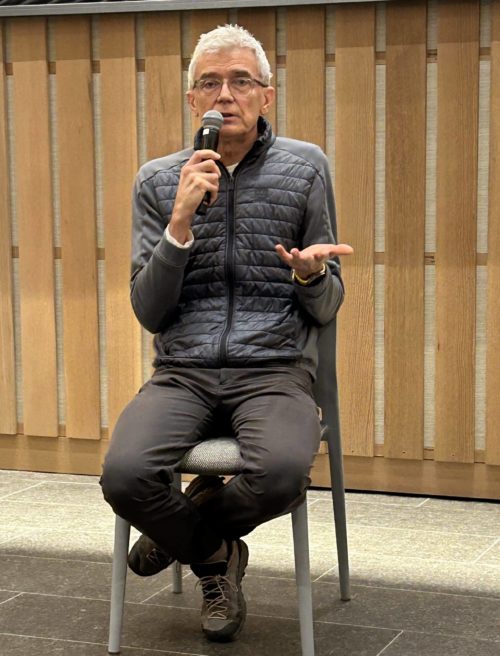

We have our resident explorer, environmentalist, investor, author, and film maker Luc Hardy to thank for enlightening some 65 of us on what is going on in the world with cloning! We were privy last Sunday afternoon to a screening of Luc’s new documentary film, “Alter Ego: Cloning, the age of Reason,” in the new Bruce Museum Auditorium. We now know there are cloned horses, camels, cows, sheep, goats, deer, dogs, cats, a rhesus monkey, and a black-footed ferret, the first U.S. endangered species to be cloned.

We can also thank Luc’s 40-year love affair with polo which has taken him often to Argentina to witness the championships for it is there he discovered some of those winning horses were clones! Fascinated, he would travel the world, to seven countries across five continents, in search of the latest science and cloning efforts.

Travel comes easy to Luc as with his Antarctic adventure, following in the footsteps of Ernest Shackleton seen in his film “The Pursuit of Endurance” he’s shared with Greenwich audiences. His investment/consulting business, Sagax Development Corp, is based in Cos Cob. But five years ago, he ventured down the cloning path halted for two years by the pandemic.

It was during a trip to the Russian Altai, where Luc begins his film where he met up with a specialist in ancient DNA, Professor Ludovic Orlando who was gathering evidence to support his theory on the domestication of the horse whilst excavating royal tombs. “The link between horse and DNA resonates with me,” Luc narrates.

It was at a World Cup polo final in Buenos Aires in 2013 that Luc learned of several victories being won by cloned horses. Luc’s only awareness of cloning was of a sheep called Dolly being the first mammal cloned in 1996, so surely, “science must have made progress in the last 25 years.” Would Professor Orlando care to join him in learning about that progress? Yes, such research might help his own research. That research would reveal for both of them “a lot of preconceived ideas, rightly or wrongly.”

In the film the two begin their research in in Pilar, near Buenos Aires, Argentina, “the birthplace of modern polo,” and “one of the world’s leading centers for cloning polo horses.” The professor “manipulates ancient DNA” in his laboratory there, along with DNA from a two-to-three-year-old horse DNA. Luc tells of the Professor’s horse cloning process in his lab. “To obtain a horse clone you need a donor mare with an unfertilized ovum…and “somatic cells taken from the neck of the original horse to be cloned…So the DNA is from one of these cells…Those cells are transferred to a surrogate mare who will give birth to a clone…containing only the DNA of the original horse.”

“The first cloned horse,” he narrates “was sold at auction for $800,000. It was born in 2010 in a laboratory near Milan, Italy…almost the only one in Europe…This was the beginning of the cloned horse craze.” He adds as an aside “Although cloning techniques have only recently been applied in the animal kingdom, they have existed for centuries in the plant world.”

Luc travels to Texas recommended as “the world reference in cloning, located in the middle of the breeding plains of Texas, one of the cradles of the equestrian world in the U.S.” At the Timber Creek Veterinary Hospital, Luc is greeted by its owner and veterinarian Dr. Gregg Veneklasen, with 20 years’ experience in cloning. “We have got lots of clones,” he tells, and his “order book is always full.” Perhaps one of his many embryos “will give birth to a future champion of rodeo or other equestrian disciplines so highly prized in the United States.”

Other rider cloning enthusiasts include those in dressage. Add that horse lover who lost her mare. The Dr. relates, “She’s calling me that her mare had died that night and says, ‘I want to clone the mare.’ So, I said, ‘Run over, get a chunk of the DNA.’ And then I put her in contact with the laboratory and they succeeded in getting the DNA for the clone and now she’s going to get her mare back,” with “every behavioral trait identical.”

Also at Timber Creek is deer cloning. “These two whitetail does are clones,” Luc is shown. He learns, “The deer business is a billion-dollar business…It’s hunting once again – they want the biggest, the fastest.” And also in Texas is a laboratory called ViaGen cloning dogs, “some with very special functions.” But Luc is learning, “Private uses of cloning are often the privilege of wealthy individuals.”

Then we’re taken to the Middle East where Luc learns, “Camel racing attracts large numbers of spectators, and the associated winnings are substantial. Also very popular are camel beauty contests. To win, it’s tempting to want to clone a beautiful specimen…Some of these beauty camels can go for two or three million U.S. dollars.” And as the camel is “a very slow reproducing animal” cloning is now being used to multiply the offspring with embryos placed in a number of surrogate camels.

Luc’s truly informative tour of the world of cloning continued, with its uses seen both advantageous and questionable. But what was also relevant were those questions in the extensive Q&A that followed the film, especially the one on human cloning. “So, you definitively agreed with the United Nations decision in 2005 to ban human cloning,” the questioner began, “But as we know with many international bans, whether it’s nuclear proliferation or whatever, there are going to be some countries that ignore bans. So it seems to me it’s inevitable it’s going to happen. And do you have an opinion of where it’ll happen and what the early purposes will be, and what the rest of the world should do in response?”

“So assuming,” said Luc, “it was possible for humans today, which we think is not quite ready, even though you can do it with primates like monkeys, it means it’s going to happen. The UN position can change. The only countries capable today of cloning mammals that we know of is Argentina, the U.S, Italy, the Emirates, and China. Now why would you clone a human? I’m not sure yet. I’ve been very open since I started this research about the subject of cloning and never try to say we should not do this.”

Renee Ketcham, president of the Alliance Française of Greenwich asked, “I think your film really talks to the viability of cloning, but it’s also very clear that the success of this cloning is extremely expensive. From the $870,000 price on the polo pony to the $5 million price tag on the camel that wins the beauty contest or is the fastest, would you say there’s a huge dichotomy between the value and the actual cost of doing this?”

“When we started the film five years ago,” said Luc, “cloning a horse in Argentina or in Texas would cost you a hundred thousand dollars. Today it’s $50,000. In five years it’s going to be $20,000…Even if it’s expensive, it’s less expensive than breeding horses and seeing which one is going to be better than the other and would make you win games.”

“Is it a fair competition?” asked another attendee of the cloned winning against the uncloned. “Yes,” said Luc. “People think so. The Argentine Polo Association says it’s okay. The players are okay with it. There are no complaints. Anybody can do it…it’s fair as far as [cloned] camels racing in the Emirates and in Dubai.”

“Maybe,” a female attendee conjectured, “We can consider cloning man to draw out the humanity of man toward loving and compassion and betterment?” “Interestingly enough,” Luc replied, “With the genomics and genetics…what’s going is just amazing today with certain animals…you’ll be able to clone a great stallion and make that stallion a mare… Because in polo, I don’t know the human world, mares are more docile and better at play than the stallions or geldings.”