By Anne W. Semmes

There’s a new exotic attraction in town, visiting at the Greenwich Botanical Center, meant to be wintering in Mexico. All five inches of her, by her species name of Rufous Hummingbird. And it was our Tree Warden Greg Kramer who first spotted her in mid-November near the Center’s greenhouses. “She is a tough little bird,” confirms an admiring Kramer. And thanks to her luck where she landed and the support that’s surrounding her, she may continue surviving until she decides to make her journey home come springtime.

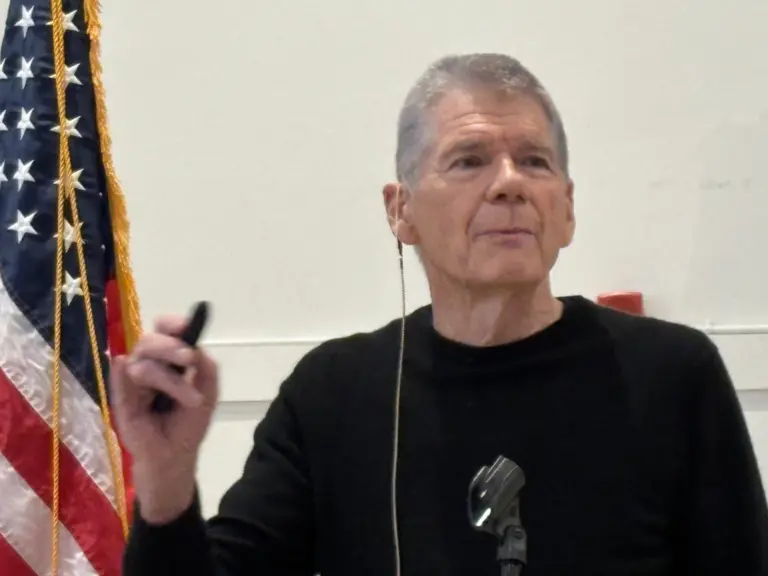

So, Kramer shared the news with birder Cynthia Ehlinger, who alerted Ryan MacLean, Senior Education Coordinator at Greenwich Audubon and Stefan Martin with Connecticut Audubon, and birder Christopher Wisker who started photographing her every day.

“It’s certainly a rare occurrence for the Northeast,” says MacLean. “The Rufous Hummingbird is a species that breeds all the way up through the Pacific Northwest and into Alaska. They can tolerate temperatures of up to negative four degrees Fahrenheit. Their actual migratory route is to go from the Pacific Northwest climates down through the southwestern United States into Mexico for the winter where it is of course warmer and there’s more food for them. But because they are a species that is from the Western United States, especially young birds (and this Rufous is determined to be a juvenile female in its first year of migration) can wind up in a weather system that pushes them out this way.” And with climate change, adds MacLean, “this is something happening more and more regularly.”

But the salvia flowers at the Pinetum feeding the Rufous were drying out so no flowers no nectar! “She would need a source of energy, a source of nutrition,” says MacLean. Messages went out – who has a hummingbird feeder? Audubon hawk watcher, Harry Wales had one in his car, and that necessary bag of sugar and MacLean knew the hummingbird mixture. “One part sugar, three parts water.” (And do avoid the over-the-counter hummingbird foods with red dyes considered dangerous to hummingbirds.).

And there the feeder hung just outside the Center’s greenhouse, and the young juvenile began to feast. Flying back and forth and hiding in the woods overnight. But a new worry arose with the oncoming freezing temperatures. MacLean would arrive to see her “just sitting there waiting for the feeder to unfreeze.” MacLean would endeavor “to try to thaw the feeder out or replace the sugar water in the feeder if it was frozen.” Then came the solution, thanks to kind individuals stepping up, “The feeder that is up now is a heated hummingbird feeder that stays thawed in extremely frigid temperatures.”

“It heats from underneath,” says MacLean, “thanks to the Botanical Center, the horticulture center allowing it to be plugged in to stay on. She has now been able to persist through this extremely deep freeze in the snow that we’ve had, which really indicates to us that she is very, very tough and that she is certainly determined to get through this despite how adverse the weather conditions have been.”

True it is she is missing those insects to give her needed protein, “But in the case of a wild bird like this,” says MacLean, “even though the feeder in itself is something that is artificial and not part of their natural diet, other artificial supplements could wind up being more dangerous to these birds than they could be helpful.” With another period of rain and a thaw expected, “She could very well be able to find insects during these periods of time.”

“We still haven’t named her,” says Phoebe Lindsay, executive director of the Botanical Center. She says the “unexpected resident” Rufous has brought a “steady flow of enthusiastic birds and photographers. “We call them the paparazzi.” Her staff and members “are flattered she chose our funny corner… We hope to make her comfortable through the winter.” And maybe they should add a questionnaire to the Center’s website for people’s suggestions for a name for their “unexpected resident.”