By Georgette Harrison, LPC

A few weeks ago, I read an article written by Dr. Peter Gray that still clangs around in my head, even weeks later. He was reviewing Bruno Bettelheim’s book “A Good Enough Parent.” As a believer in good enough parenting, I was intrigued to read Dr. Gray’s opinion of the book. He pointed out a quote from the book that resonated deeply with me: “There are few loves which are entirely free of ambivalence… Not only is our love for our children sometimes tinged with annoyance, discouragement, and disappointment, the same is true for the love our children feel for us.”

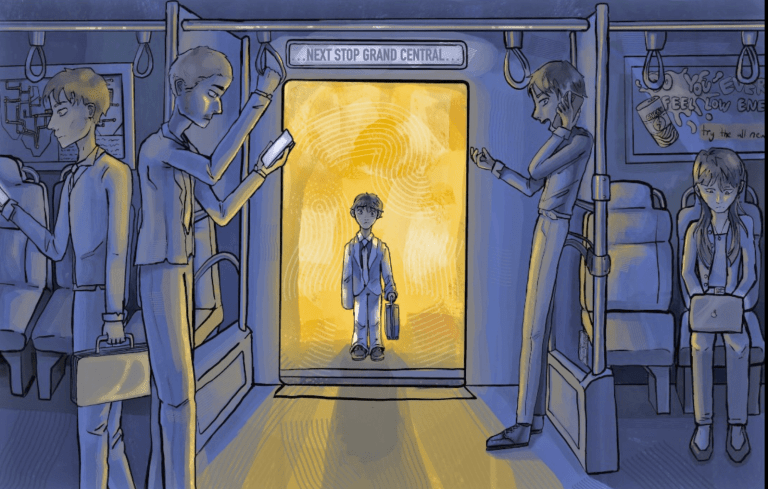

As parents, we often talk about the depth of feelings our children evoke in us. A good moment with our child can make us feel a heightened sense of happiness, love and contentment, in a way that few other relationships make us feel. An argument, particularly a very bad one, can make us feel angry, confused, rejected, and it can keep us up at night, mulling over every word said. There are few other loves that stretch our hearts to their limit and beyond. However, the quote also reminds us that “the same is true for the love our children feel for us.” I believe part of the reason the article stayed with me for as long as it has is because it highlights the way in which we may sometimes disappoint our children, and that the love our children have for us also stretches their little hearts to their limit and beyond.

As a good enough parent, we know that perfection isn’t only unattainable, it’s actually detrimental to the parent-child relationship. Not only should we not expect perfection from our child, we shouldn’t expect it from ourselves. Every relationship is marked by those moments of disappointment, missed opportunities to connect, times when our own points seem so important to make that we drown out the voice of the person in front of us (or vice versa). In the attachment literature, those moments are called ruptures.

Ruptures aren’t bad. Healthy relationships aren’t characterized by the absence of ruptures. To borrow from Benjamin Franklin, “in this world, nothing is said to be certain, except death and taxes”… I would add “and ruptures.” It is the repair that occurs after a rupture that helps to build a stronger bond between people. The act of repairing, of coming back to the table with love, curiosity and humility is what teaches our children that relationships are strong enough to weather any storm.

However, I often hear parents say that they feel justified in their actions: “If I don’t scream at him, he’ll just think I’m letting him get away with it,” “If only she listened to me the first 100 times that I asked her to put on her shoes, I wouldn’t have to get angry.” As a parent, I also often feel justified in my actions, so you are not alone. However, if we dig deeper, there’s an underlying fear that to come back to our child and say “I’m sorry that I screamed/lost my temper” will remove parental authority in the eyes of the child. If we dig even deeper, we might realize that we have seldomly experienced this degree of repair with our own loved ones and so we’re unsure of how to go about the business of repairing.

This is not to say that the occasional raising of your voice or losing your patience is harmful to your child: it’s not. It’s important for children to see their parents as people who also lose their patience and that their behavior has an impact on their parents. What looms large in a child’s memory, and creates a template for future relationships and teaches them how to mend ruptures (or not), is the aftermath. If your child can experience those inevitable ruptures and consistent repairs with you, they will learn that what you value most is not gaining the upper hand, or “being right.” What is most important to you is your bond with your child. Just as important, they begin to learn that they are important (and loveable) enough for others to want to repair with them, and will come to see repairs as the hallmark of a healthy relationship. In other words, they come to view themselves as worthy of repairs, and will be more likely to recognize unhealthy relationships in the future.

The moment of repair is also important. We can’t just say we’re sorry, but not actually feel regret for the impact our actions have had. Approach your child when you’re calmer and ready to listen. We have all had the experience of someone who says to us “I’m sorry I did that but…” Imagine that every time you say “but,” you’re essentially deleting everything you said before. It doesn’t mean that you don’t talk about how and why things escalated, but that comes after the repair: “I’m sorry I screamed. I lost my temper and I’m sorry that I hurt your feelings. You are very important to me.” Full stop. No explanations or justifications, just listening. Don’t expect your child to readily say sorry themselves or to even say that you’re forgiven. It may take time, but they’re learning from you that saying sorry and being vulnerable is ok and safe in the context of your relationship. However, be confident in the knowledge that you are planting the seed that will lead to healthier, stronger relationships with you and with others. Your child might even surprise you in the future by coming to you and saying “I’m sorry I did that. I shouldn’t have and I’m sorry I hurt your feelings. You’re important to me.” I promise you, it happens.

If you are stuck in a constant loop of arguments or need support in becoming closer to your child, we are here for you. Don’t hesitate to call the Child Guidance Center of Southern CT at 203-324-6127 for assistance. More information is available on our website: https://childguidancect.org/