By Emma W. Barhydt

When Sheryl Berk talks about Big Man, she begins with place and family. Her father-in-law, Alan, “raised his family in Greenwich. They lived there forever… and he was the vice president and the treasurer at the Bruce Museum, and very involved in Greenwich.” Years later, after moves to Rye Brook and Stamford, the family moved him “into Edgehill’s Memory Care. So it’s been a journey. It’s been quite a journey.”

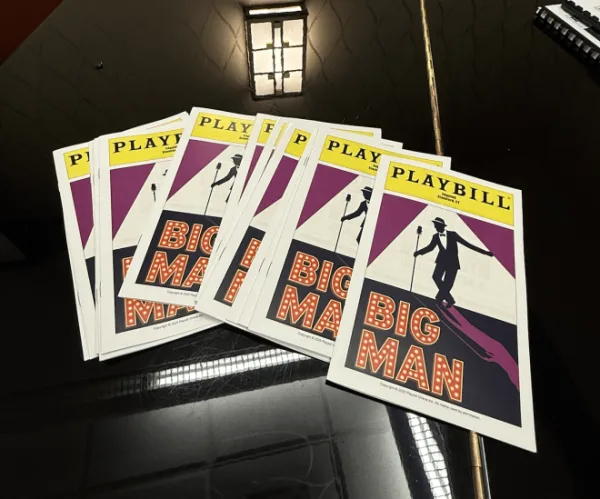

Though Berk spent years writing about theater, she had never imagined she would write a musical herself. “I’ve always loved theater. I’ve always been a theater journalist,” but one afternoon at the Edgehill Grill changed everything.

Her father-in-law, “was a little out of sorts that day… confused… sad and tired,” she recalled. Hoping to lift his spirits, she showed him photos from a Sinatra exhibit. “I said, have you ever seen him in concert?” What happened stunned her. “His face lit up like the Vegas strip… He just started telling me these stories… ‘I saw Frankie in concert. I shook his hand, and then I had a drink with him.’” When she asked what Sinatra drank, he replied instantly, “Jack Daniels double on the rocks.”

Across the table, her mother-in-law quietly indicated the stories weren’t real. But something unmistakable had been awakened. “As if we had planted a seed,” Berk said. Before dementia, Alan had never shown particular interest in the Rat Pack, “In the 25 years I’d known him… I never heard him mention the Rat Pack once.” Now, “this era of life and of music symbolized something to him that was an escape from the life he was living.”

The family followed him into that world. “We learned to lean into it,” she said. Soon he was saying, “The man is coming for me today,” arriving “in a private jet,” or announcing he was headed to “Vegas… maybe Paris this week.” Once, “he put on a jacket over his pajamas… held his old briefcase,” and waited in the driveway for the imagined helicopter.

Because these stories lifted him, the family embraced them. “For the first time, it wasn’t trying to ground him into reality… If this makes him happy, then let’s go with it.” Her husband hung a Rat Pack canvas in his room; her brother-in-law made a playlist. Edgehill’s staff joined in. “Everyone started using Sinatra’s music to motivate him,” she said. With a song like High Hopes or My Way, “he’d start to sing.” The effect was unmistakable, “It became such a bridge for us.”

At the same time, Berk was watching her mother-in-law carry the daily strain. “It was such a weight, but she handled it with grace and grit,” she said. “He never forgot who she was. And he asked for her every single day.” She became aware of how rarely caregivers are acknowledged. “We’re always asking, how’s the patient… but we never really ask the caregiver, how are you doing?”

When Berk played her a song from an early draft, her mother-in-law told her, “You truly get it.” Berk held onto that. “I want every caregiver who sees this to just go, wow, I feel seen. I feel heard.”

This conviction shaped the musical. “People say, what’s it about? And I always say it’s about memory, it’s about imagination, but it’s also really about the people who care for us when we can no longer care for ourselves.”

She created two adult children based on “very common caregiving types.” The son is “very hands-on, overwhelmed, part of the sandwich generation caring for both his father and his children.” The daughter, “keeps her distance, overwhelmed by fear and guilt,” and holds onto, “a narrative she’s built around who her father is, which isn’t necessarily the correct narrative.” Together they reflect, “the complete spectrum of caregiving reactions from really deep involvement to avoidance.”

Meanwhile, their father’s interior world is vibrant. “His fantasy world of Vegas is like Vegas on steroids,” Berk said. “He doesn’t just see neon, he sees technicolor neon. He sees acrobatics.” His late wife appears young and alive, and, “He’s earned that right to be in it.”

The title character—the “big man”—comes from the energy that transformed Alan at the lunch table. “If you took Sammy Davis and Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra… that’s the big man,” she said. The music is entirely original, “Let’s take rat pack music and put it in a blender… What would 2026 Vegas sound like?”

For Berk, the story resonates far beyond her family. “Millions of families around the world really are living with caregiving,” she said. “You’re trying to navigate a loved one’s dementia while managing your own world, and your grief.” The statistics she cites are unignorable, “Over 60 million Americans are family caregivers. It’s basically unpaid labor, and one in four caregivers reports that they feel invisible.”

She believes theater can shift that reality. “Theater has the power to empower,” Berk said, “with theater, you’re sitting inside another person. You are watching this story unfold, but you’re part of it at the same time, and that is the power of theater beyond any other kind of storytelling.”

Berk traces the musical’s origin back to one table at Edgehill. “This was born at Edge Hill,” she said. “I literally was sitting here having lunch, and I thought, I’ve got to write this.” Team Edgehill—a group of residents—raised over $100,000 for the Alzheimer’s campaign on the night the songs were performed. Afterward, Berk went table to table. “People would tell me stories about my father-in-law,” she said. “It was really amazing.”

Fittingly, the musical’s first test came at Edgehill, where Berk presented six or seven songs. “They sold out the tickets, they actually had a room for overflow,” she said. When the cast performed “Wander,” the room changed. “We looked around, everyone was crying,” she said. Afterward, one man told her, “My wife passed away in May of Alzheimer’s, I feel like you gave her a voice.”

That kind of response has grounded her. “I stumbled through being a caregiver,” Berk said. “We stumbled through every day, so that’s what I’m kind of doing with this. I’m stumbling forward.” Families often ask her how to do it. “There is no easy answer,” she said. “You do it as a family and you do it with love. There’s no magic formula, it’s just leading with love.”

What she wants most now is to extend that feeling. “If I can translate that kind of feeling of community into an audience and do it for each show,” she said, “I will be the happiest person ever.” As for what’s next, Berk noted “a 29 hour equity reading,” a 2026 benefit concert, and, “a concept album with Broadway talent,” with proceeds directed toward Alzheimer’s-related causes.

Through it all, she returns to Alan—whose stories, real or imagined, sparked everything. “People say, where’d you come up with this story idea?” Berk said. “And I’m say, I didn’t come up with it. My father-in-law lived it.”