By John Engel

For two years, the U.S. housing market has been defined by one stubborn fact: Nobody wants to give up a 3% mortgage.

For two years, the U.S. housing market has been defined by one stubborn fact: Nobody wants to give up a 3% mortgage.

Even as interest rates climbed above 7% this fall, the “lock-in effect” kept listings low and inventory throttled. Now that rates have drifted back toward 6% — with credible forecasts suggesting 5% mortgages sometime in 2026 — you might think sellers would finally loosen their grip.

They haven’t.

Across Fairfield County, would-be sellers are still doing the math: If I move, my monthly payment doubles. So, they stay put. Downsizing delayed. Job relocations postponed. That “move-up” plan put off indefinitely.

And while sellers are frozen by rates, policymakers are scrambling. New York City Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani just ran — and won — on an affordable housing platform. In Connecticut, HB8002 dropped Friday, another attempt to tackle affordability. And on the national stage, Donald Trump floated 50-year mortgages, a tool Japan uses to lower monthly payments. The idea is not new, but the political timing is telling.

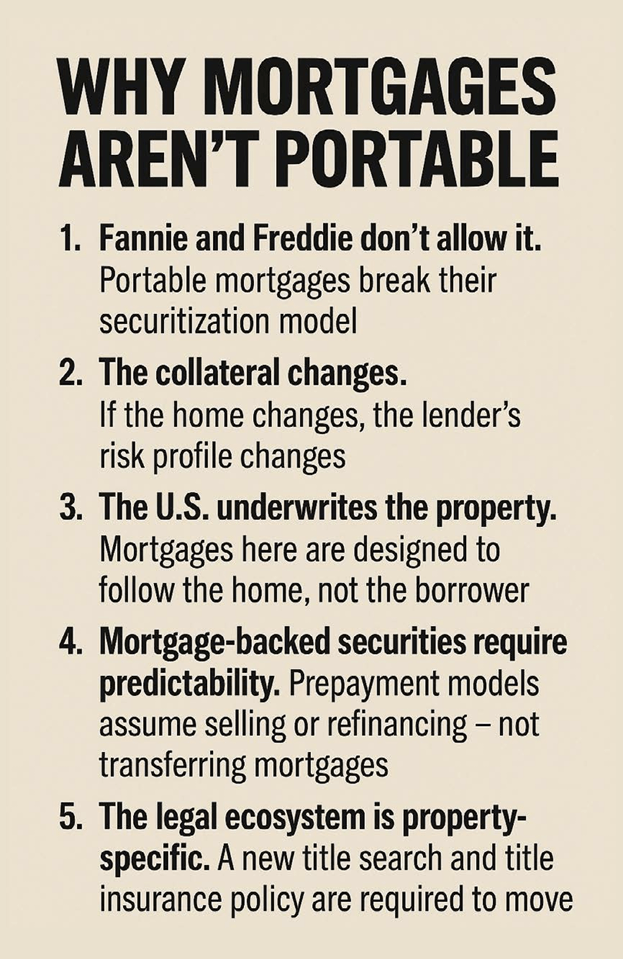

My favorite solution: there is early talk of portable mortgages, loans you carry with you from house to house, preserving your original interest rate. That one innovation alone would end the lock-in effect overnight.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world plays a completely different mortgage game. Japan stretches repayment periods to 50 years and, during the bubble years, even toyed with 100year, multi-generation loans. But that’s the outlier. In Europe, Canada, and Australia, a “fixed rate” usually means five years, not thirty. Most countries don’t offer 30-year fixed mortgages at all. Those short terms force people to refinance, move, and stay flexible. Our long-term fixed loans do the opposite: they create stability — and now, stasis.

The U.S. is the only major country where the 30-year fixed is mainstream, government-backed, widely available, and consumer-friendly. Why? Because other countries don’t have Fannie and Freddie, their banks won’t take decades of rate risk, and their central banks discourage ultralong fixed terms.

This week on Boroughs & Burbs (Episode 209, “Creative Titles”), we heard a story out of Colorado that illustrates how all this pressure shows up at the household level. A homeowner accepted an offer, used it to purchase their next home, and went under contract. Then their buyer walked. Suddenly they owned two houses, two mortgages, and had no path forward.

Rather than default, they brought in a “partner” — a private individual who took title and made the payments until the home could be sold or rented. Perfectly legal. Clearly a violation of the mortgage. But faster and cheaper than foreclosure, and far less damaging to a credit score.

This is the gray zone a growing number of owners find themselves in: caught between a failed sale and a foreclosure, with no bridge product — financial or legal — that moves fast enough. It’s why “creative title” companies are thriving in states where the system itself is more flexible.

And the same pressures that push homeowners into gray-area fixes also invite something darker. Fairfield County has seen a rise in impersonation attempts, including the well-known Fairfield case where a scammer sold a doctor’s land for $350,000 and a $1.45 million home was built before anyone realized what had happened. The developer had both an attorney and a title policy — but the policy covered only the land. It was a reminder that even conservative systems have blind spots.

These scams aren’t isolated incidents. I’ve personally witnessed four impersonation attempts, including one here in New Canaan just last month. None of them closed, but the frequency tells us something important: Fraud is becoming more sophisticated, even in cautious, attorney-driven states like Connecticut.

All of this raises a bigger question: Why don’t we see more “creative” financing in Connecticut?

The answer is simple.

Connecticut (and New York) are attorney states. Every transaction funnels through two lawyers whose job is to prevent anything that looks like risk, ambiguity, or rule-bending. Colorado, Florida, Texas, and much of the country are title company states. Their system is built for speed, not conservatism. If someone wants to add a silent partner, subordinate a lien, or engineer an unconventional workaround, the title system is more accommodating.

But the underlying pressures are the same everywhere:

1. Rates are still too high for mobility.

Even with current rates at 6%, a homeowner with a 3% loan is economically trapped. Until mortgage portability or creative products emerge, the lock-in effect will persist.

2. Failed sales require a true bridge solution.

When a buyer walks, the seller may still be on the hook for the next house. Bridge loans and HELOCs don’t always solve it. “Partners” and gray-market workarounds exist because the market is demanding them.

3. Affordability is now a political issue.

From Mamdani in New York to HB8002 in Hartford to the sudden appearance of 50-year mortgages in the national conversation, the pressure to create new tools is building.

4. Fraud is rising because the incentives are rising.

A frozen market is fertile ground for impersonation scams. Criminals understand the value of land in this region — and the friction that slows the system is also what creates openings.

5. The system itself needs modernization.

Attorney closings provide due diligence and protection, but they also add cost, time, and rigidity. In a tighter, more volatile market, consumers need flexibility as well as protection.

Notes from the Monday Meeting:

We reduced the price on our Darien listing last week (one of only 20 houses for sale townwide) and saw 20 groups through the open house. Was it the price reduction? Or the Mamdani effect — people suddenly feeling that affordability is back on the table? Only one couple blamed Mamdani for the move. Momentum matters.

John Engel is a broker with the Engel Team at Douglas Elliman. This week, he is stacking logs and building fires. When he lived on a fifth of an acre, he bought his wood from Carlo, an 80-year-old from Redding who makes his own wine. Now, John lives on four acres. Trees fall all the time, about two cords each winter. John’s house, built c.1800, would have consumed somewhere between 20 to 40 cords a year in Colonial times, which meant maintaining a wood lot of 15 to 20 acres just for heating and cooking. Think about cutting 20 acres by hand with an axe! Today, we complain about high utility bills, when all we need is a sharper axe.