The Oral History Project – Celebrating America 250: Edward Vick – Proud American

By Mary A. Jacobson

Edward Vick’s family has proudly served in the United States military for generations. In his 2024 Oral History Project interview with Mary Magnusson in 2024, he reviewed both his and his family’s military history.

Vick’s great-great-grandfather, Joshua Vick, led a company of the 7th North Carolina Regiment in Gettysburg. Wounded, captured, and later released, “he was one of the lead elements of Pickett’s Charge.” His grandfather participated in the First World War. “He went to France as a motorcycle dispatch rider.” Vick’s Uncle George, “who I was very close to… ran away from home when he was sixteen and went up to Canada and joined the Royal Canadian Air Force and flew Mosquito bombers in Europe” during World War II.

Vick’s dad had the greatest influence on him. A medical doctor, he was made a junior officer in the Navy and a medical officer. “He was in the Battle of Okinawa on a ship, and he was treating the wounded on an open deck while the kamikazes were crashing all around him… He received the Bronze Star for that.”

With that legacy of military service in his family, it is no wonder that Vick also wanted to serve his country by joining the military. A graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, “I joined the Navy because my dad had been in the Navy.” Vick was twenty-two in 1966 and the Vietnam War was raging. Vick was initially assigned to a ship in Boston Harbor. “I didn’t want to do that. I felt like I really wanted to be in Vietnam. I suppose my feelings changed later on, but I really believed in the war at the time.” After a year, he asked his commanding officer if he knew “anybody in the River Patrol Force of the swift boats or anything like that?… So next thing I knew, the orders got changed and I was off to San Francisco to train for riverine warfare.”

Vick’s four-month training program involved small boat tactics, “daytime and nighttime, up in Vallejo, California, in the northern side of San Francisco Bay,” survival school, and Vietnamese language school. “And then I was sent to Vietnam right before Christmas in 1968” at age 24. Upon arrival, Vick learned that he would replace another junior officer who had been killed. “I was told that I was going to be assigned to River Division 534, which was up on an operation called GIANT SLINGSHOT, northwest of Saigon and it was a really difficult operation.”

Vick found this first foray upriver to be “quite an eye-opening experience. Nothing was like what they taught you.” These were not the big rivers upon which he had been trained. “They wanted to get more up into where the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese really hung out. So, we had to go into more narrow rivers which were much more dangerous… the Viet Cong would line up along the riverbanks. They’d build bunkers… and they’d wait for you to come by and they’d open fire… My very first gun fight, my boat was hit by a rocket below the water line, and we sank.” Fortunately for Vick, “All patrols moved in pairs because they were so vulnerable. They’re just plastic with no armor… So, my cover boat behind me saw that we’d been hit and were going down.” Fortunately, they all survived.

Other times, with a starlight scope – like a night vision goggle, Vick’s platoon would wait in silence to ambush an expected Viet Cong crossing of the river. “We’d tie our boat up to the bank and we’d turn all the radios and everything off. We wouldn’t talk. We’d just lie there and wait all night long. No smoking. No nothing… And then you could see them crossing. And they wouldn’t see you. So, we would catch them sometimes crossing late at night… And that’s what you were trained to do.”

All in all, Vick commanded about a hundred patrols in the area of the Mekong Delta and was awarded two Bronze Star medals. “One of the things I’m most proud of is we were awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for our actions in GIANT SLINGSHOT, the highest award that a combat unit can receive for its actions in combat.”

When Vick returned from his tour in Vietnam, he enrolled at Northwestern for a master’s degree in journalism, a small program of about thirty students. “I hadn’t been home for three years basically. And when I came back, the attitude towards the war had completely changed and vets were completely ostracized.” One university experience at that time was seared in his memory. On the first day of class, the professor asked everyone in the program to tell something about themselves. “So, everybody goes around and it comes to my turn. So, I said, ‘Well, I’m from Philadelphia and blah, blah, blah. And I went to the University of North Carolina.’ And that’s all I said. And the dean said, ‘Wait a minute. Wait a minute. You forgot the most important part.’ The dean was a reserve naval officer. So, he was proud of the fact that I was a naval officer in Vietnam. And for the next two months, nobody spoke to me. Didn’t say anything to me. No, didn’t say a word.”

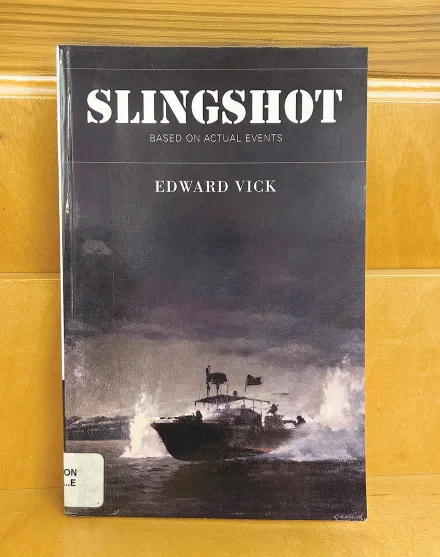

During that time, Vick started to write his book entitled “Slingshot.” He was “beginning to turn against the war… It’s basically good guys caught up in the web of the system and the bureaucracy. And it doesn’t come out well… The American population blamed the war on the warriors, not on the politicians.”

Vick’s professional life in the years that followed saw him rise to be CEO of the firm Young and Rubicam. His personal philanthropy centered on causes that benefitted veterans. While Mayor of New York, Ed Koch appointed him to the board of the New York Vietnam Veterans Memorial Commission. “That was quite an honor.” A jobs program for veterans was initiated. In addition, a book entitled “Dear America: Letters Home from Vietnam” was published and later turned into an Academy Award-nominated film. “It was a book of nothing but letters home from Vietnam. No editorial comment or anything like that. Just letters.”

Vick was also on the board of an organization called “Give an Hour” which pairs those in need of psychological help with a psychiatrist or psychologist for an hour a week free. “And we have seven thousand psychiatrists. So, it’s really quite a good program.” He is also often seen on the parade route of the Greenwich Veterans Day parade or as a speaker at the annual Memorial Day ceremony at Indian Harbor Yacht Club.

Looking back at his accomplishments, Vick surmised, “I learned hard work in the Navy, and I learned responsibility. I learned leadership. I just learned a lot of things in the Navy. It stood me in good stead.”

The Oral History Project is proud to present blogs derived from its collection of recorded interviews as part of the Project’s celebration of America 250 Greenwich – Greenwich History is American History. The OHP is sponsored by Friends of Greenwich Library. Visit the website at glohistory.org. Interviews may also be read in their entirety or checked out at the main library. They are also available for purchase by contacting the OHP office. Our narrator’s recollections are personal and have not been subjected to factual scrutiny. Mary Jacobson serves as blog editor.