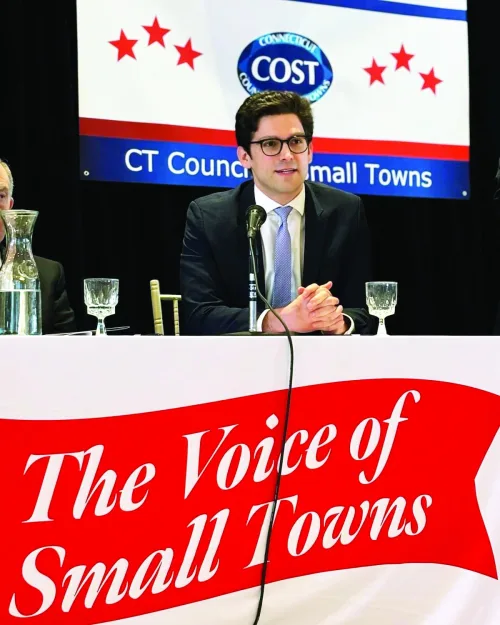

Ryan Fazio is running for governor, and he is doing it the way he has done everything else in his political career: with the unglamorous insistence that the public has a right to know.

In Connecticut— where so much happens behind closed doors — pension fund investments, billion-dollar healthcare deals, and, most recently, the anti-local legislation known as 5002 — Fazio has made transparency his guiding principle.

“Al l of us as electricity consumers have been paying hundreds of millions of dollars a year in public benefits charges,” he said in a recent interview, referring to the quietly levied fees tucked into electric bills. “Until last year, nobody knew about this until I passed a new law that requires those charges to be itemized on every person’s utility bill. People were already upset that their electric bills are the third highest in the country — now they can see that about 20% of those bills are funding non-essential programs that have nothing to do with the electricity used in their homes and businesses.”

He sees this as the heart of the matter: sunlight, then reform.

His campaign reflects the same energy. Fazio started on August 13, when most of the state was at the beach. Forty-four days later, his campaign has raised around $100,000 from small donors — almost a third of the way to qualifying — outpacing other candidates on a per-day basis. “If we’re above $100,000 by filing day, we’ll be ahead of where the others were per day at the start of their fundraising,” he said. It is not the cash alone that is notable, but the campaign’s momentum from endorsements: from both the State Senate and State House Republican leaders and the most endorsements of any candidate from Eastern Connecticut—which has both the most Republican officials and is the farthest part of the state from Fazio’s senate district.

The candidate from Greenwich, sometimes criticized for being “too Fairfield County,” is drawing some of his strongest support from the other side of the state.

The timing of his message could hardly be sharper. The governor’s veto of House Bill 5002 — the most significant housing bill of his tenure — came after days of private consultations and a string of revealing text messages, now public through FOI requests. The messages showed legislators voting “no” for political reasons while privately urging the governor to sign the bill. “It totally exposes for everyone to see the whole ‘vote no but hope it passes’ strategy,” Fazio said. “You can’t make it up.”

For Fazio, this is the point. “People ask questions about how state government is operating,” he said. “They deserve answers.” In his telling, the public’s trust is not just eroded by bad decisions, but by the secrecy that precedes them.

He hears the same thing in every corner of the state — Southington, Old Lyme, Glastonbury — people who bring up 5002 and the question of local control without prompting. “Local control is important to people all across the state, more so than you would think,” he said. “The issues we emphasized in our Senate campaigns are the issues most important to people statewide.”

Governor Lamont’s office has promised a special session to revisit the bill. Fazio remains skeptical. “Nobody knows what’s going to happen — it’s very much between the administration and the majority leaders,” he said. “Everything keeps being done behind closed doors.”

This is where he draws his contrast. With such a vast majority, legislators vote NO understanding the bill will pass anyway. Then they quietly text the governor from the f loor urging him to sign the bill they just voted against so that their constituents won’t know.

Fazio says one of the jobs of a governor is to “open the windows.” He sees the public benefits charge as a case study.

“Transparency was vital to providing the public with an understanding of what was going on and why their electric bills are so high,” he said. “It’s also vital to actually passing legislation to cut those charges and make electricity more affordable — which is a top priority of mine.”

His critics call it inside baseball, the talk of policy wonks. But Fazio insists it is connecting. “I wasn’t sure one way or the other,” he admitted. “But it turns out people across Connecticut really care about these issues — and local control is a priority for them.”

What Fazio is learning is that the fight over 5002 is more than a fight over parking minimums or density unit counts. It is a referendum on how Connecticut governs itself — who listens, who explains, who decides.

Lamont’s veto, whatever its prudence, left members of his own party saying it will be hard to trust him in the next negotiation. Voters are watching — and Fazio is speaking to them in a language that sounds like the opposite of a backroom.

The official filing is not for another four days. But if his campaign continues at its current pace, and if the theme of sunlight continues to animate his travels — from Greenwich to Windham, from Ridgefield to Norwich — Fazio may find that his call for transparency and local decision making— transforms his fast start into a long haul.