If you want to live to 100, you could move to Okinawa, Japan, where they eat purple sweet potatoes and belong to life-long social circles called moai. Or you could join the hillside shepherds of Ikaria, Greece, who nap daily and cook with wild herbs. Or you could stay put here in Greenwich—and learn what these places know.

In the early 2000s, journalist Dan Buettner identified five “Blue Zones” across the globe where people live significantly longer, healthier, and happier lives. The secret, he found, was not kale or crunches. It was the gentle, persistent architecture of their lives: plant-based meals, natural movement, daily purpose, tight-knit social circles, and environments designed for connection rather than convenience.

“The key,” Buettner has said, “is not discipline—it’s design.”

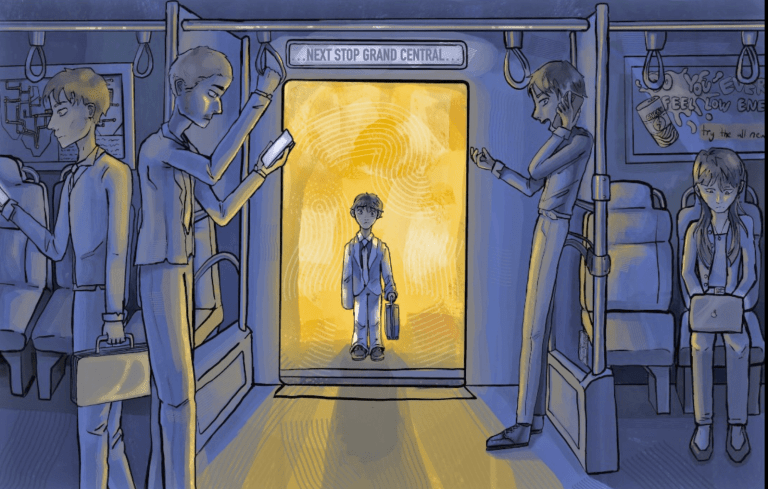

Which brings us to Greenwich. We have good schools, clean parks, medical excellence, walking trails, and a Whole Foods which delivers. But we also have something else that the Blue Zones avoid: chronic stress, rising loneliness, and a rising tolerance for meanness in public and private discourse. That’s not just unpleasant. It’s dangerous.

Medical studies now confirm what grandmothers and philosophers have always known: unkindness is a health risk. Sustained emotional stress—from social friction, bullying, or public shaming—elevates cortisol, impairs immune function, and shortens telomeres (the body’s cellular clocks). Inflammation rises. Memory fades. Brain scans show accelerated aging in those surrounded by negativity. “If you want to ruin your own memory later in life,” writes Buettner, “spend a decade being angry.”

So let us be clear: people who act with cruelty, online or in person, are not just being “real.” They are subtracting years from the lives of their readers—and hurting their mental acuity. A sharp tongue can take a real toll on the nervous system. Constant derision corrodes trust. A culture of contempt is a threat to public health.

Which is why, in this moment, we must do something rare: ask each other to stop. Calmly. Kindly. But firmly.

We can say: That’s not how we speak to one another in Greenwich. We can say it in our town halls and our PTA meetings. We can say it when someone mocks a neighbor on Facebook. We can say it in our homes and in our hearts. Because this is not just about being nice. It is about being well.

You don’t have to move to Sardinia to reap the benefits of a Blue Zone. You can create one right where you are—by rethinking your pantry, your schedule, your circle of friends, and by what you choose to read. Buettner recommends simple starts: cook plant-based meals a few times a week. Go for a walk after dinner with someone you care about. Keep healthy food in view. Meditate for 10 minutes. Take a nap. Invite a friend over for tea. Eat slowly.

But perhaps the most powerful act of all? Choose kindness. Let it shape your tone, your conversations, your assumptions. Let it be the air your family breathes, the spirit of your community. We cannot out-medicate loneliness.

We cannot out-exercise bitterness. But we can, with small daily acts, make Greenwich a place where people flourish—not just longer, but better.

In The Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle wrote that “the whole is greater when its parts are in harmony.” We can make this town not only one of the safest in America, but one of the strongest in spirit and clarity of mind. Chronic hostility—lived in, witnessed, or absorbed—does not simply wound feelings; it degrades the brain itself, eroding memory, dulling thought, and hastening decline. Choosing civility, then, is not merely about being nice. It is about preserving the very faculties that let us love, reason, and belong. To reject meanness is to protect each other’s futures. To live kindly is, quite literally, to keep each other whole.