By Anne W. Semmers

Daniel Ksepka, in his 11 years as Curator of Science for the Bruce Museum has acquired fame with his bird fossil discoveries. He’s named the world’s largest flying bird and discovered the world’s largest penguin (a flightless seabird). But today he’s partnered in a new discovery of bird fossils found in Alaska, north of the Arctic Circle, dating back 72 million years, the age of the dinosaurs, identified as migratory birds breeding in that freezing part of the world.

Ksepka spells out the significance of this finding. “Prior to our discovery, the oldest record of birds breeding in the Arctic or Antarctic came from fossil penguin bones (including young birds) discovered on Seymour Island, Antarctic. Those bones are about 40 million years old. So, our discovery pushes that back by about 32 million years.”

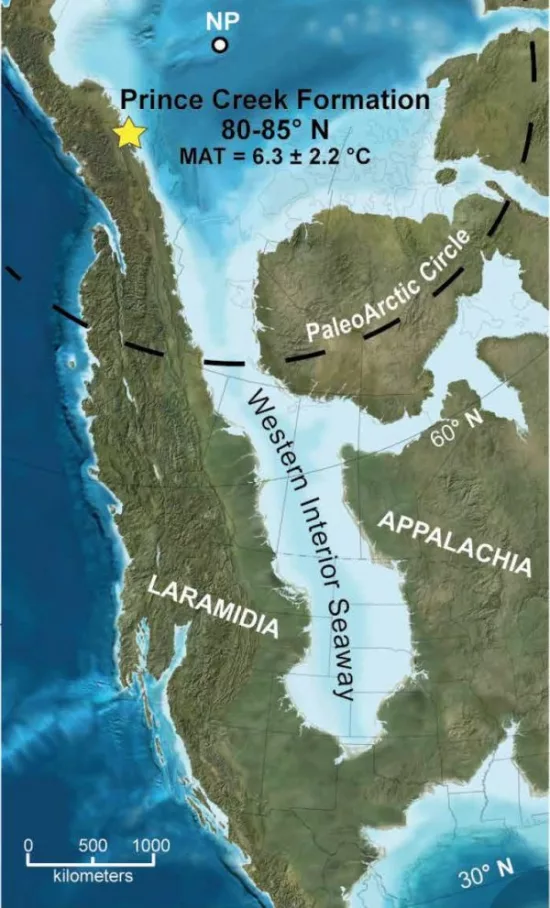

“So, the discovery was of all these little bird bones (including from embryos and hatchlings), which is amazing… Alaska was farther north during the Cretaceous period…. The continent drifted south. And so, when you’re up that high, you’re having more than a hundred days a year where it’s dark 24 hours a day. And on the other side of that coin, you have more than a hundred days of perpetual sunlight in the summer.”

And in those 100 sunny days he tells, “The plants are growing rapidly. There are bugs. That’s what they’re eating. If you’re something that eats fish, there’s a lot of plankton and there’s a lot of fish… and when you leave the lights on 24 hours a day, you’re safer from predators. So, think about a fox or raccoon raiding a nest at night. These nocturnal predators, they can’t sneak up on you.”

The discovery team

Ksepka wasn’t there for the actual bird fossils discovery. But his story goes that at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks Princeton PhD student Lauren Wilson was working on her master’s thesis centered on her research – with contributions of nine other team members – in the finding of bird fossils across several field-hunting seasons. He cited Wilson as a “brilliant young woman doing amazing work.” She was introduced to the director of the Museum of the North at the University of Alaska, Pat Druckenmiller with his passion for collecting fossils in a place called the Prince Creek Formation. “And amongst those Cretaceous period rocks,” says Ksepka, “he found dinosaur bones and then a bunch of bird bones.”

Ksepka with his bird fossil finding fame was recruited to serve on Wilson’s thesis committee and be a part of the documenting team of the discovery with Wilson as “lead author,” and Druckenmiller as co-author. But Kspeka notes, “This is Lauren’s project more than anyone else’s.”

The discovery made the cover of Science magazine last week and has since spread across the world. And those found bird fossils include more than one species. Ksepka describes some of them as illustrated on the Science cover with dinosaurs included. On the left are seagull looking birds – “these are more primitive birds that still had teeth in their beaks. They probably had a tern-like morphology…living in aquatic environments.” Yes, one has a fish in its mouth.

On the right of the image are a gathering of striped baby birds, the more “modern” birds. “These are toothless,” he tells adding that “all the babies seem to belong to this type of bird.” A larger one resembles a duck.

Ksepka shares another image demonstrating just how tiny those bird fossils were, as placed on a penny. “Those are pieces of the feet, bones, and skull bones. This is why this fossil site people had thought was tapped out already… But the University of Alaska crew went back…bringing big blocks of sediment into the lab, and then carefully picked through them. You’re sorting it under a microscope, and then you find these tiny treasures…It’s a vast undertaking, but it’s worth the results because it tells you so much.”

Fossil sizes and names

So, what sizes are these birds? “They’re on average about the size of a morning dove – they’re not hummingbird size, but they’re nowhere near an eagle… And being small, you don’t want to be trying to tough out the winter. They probably went south.” And what’s “so cool” to Ksepka is that those birds were “living alongside the same Pachyrhinosaurus dinosaur that is outside the entrance to the Bruce Museum’s Steven & Alexandra Cohen Education Wing!”

So, when will there be a scientific naming of these varied bird fossil species?

“We know what groups they belong to, but we haven’t named any of them. So, the problem is all of the bones are scattered…we have a wing bone, a foot bone, and a beak. But because they were found in this riverbed environment, we don’t know which ones go together. And so, we don’t want to make any assumptions that might look foolish later. So, until we find the skeleton united, we’re going to call them by three different types of birds.” The first is that toothed seagull that belongs to the now-extinct group called the Ichthyornithes. Another group he named for a shortwinged diving bird that propels itself with its feet was Hesperornithes. And then there are “those modern birds that look like ducks, Neornithes,” a group that includes all living birds.

Ksepka looks upon those bird fossil finds as “a really important discovery.” Those bird fossils represent “some of the most abundant Cretaceous birds known from North America. There are dozens of bones, and they’re so rare in the United States that this adds a lot to that record as well.” But in the final analysis for Ksepka the discovery of the “migration and the nesting” exhibited with these found bird fossils is “the real heart of the story.”