By Anne W. Semmes

Davidde Strackbein, the town’s leading historian, was the guest speaker at the Second Congregational Church’s monthly Women’s Fellowship luncheon meeting. Strackbein, a trustee of the Greenwich Historical Society, focused on nearly a dozen historic Greenwich “Great Estates” with a rare three-dimensional view, including the individuals of those estates, often noting the related women – in recognition of Women’s History Month.

She cited the year of 1880 as the beginning of Greenwich’s transformation “from a primarily farming community of clever farmhouses into estates and manor houses in the European tradition…when New Yorkers with untaxed fortunes built monuments to their newfound often extraordinary wealth and power.” Such as William Rockefeller, with his Standard Oil Company fortune.

Wintering in New York City, Rockefeller “met and married a Connecticut girl, Almira Goodsell from Fairfield,” told Strackbein. Almira had earlier purchased property in Greenwich in 1877 upon which they built a summer home on Putnam Avenue featuring “a multiplicity of soaring towers …which stood where Whole Foods is today.”

Louis Comfort Tiffany was employed “to create decorations for the walls of their new home using imported Japanese paper which was rare at that time,” said Strackbein, creating a residence, “which without doubt was the most elegant and finely situated home in the town of Greenwich.” Add to that Rockefeller’s purchase of 100-acres plus off Lake Avenue to create a “gentleman’s driving association,” a portion of which would become Deer Park.

Louis Comfort Tiffany would also be called upon to decorate “the first great estate designed in the European tradition in Greenwich,” the 32-room summer mansion of Jeremiah and Elizabeth Lake Millbank. “The estate was entered through the majestic gates that still stand at the corner of Putnam and Millbank Avenue opposite the Second Congregational Church noted Strackbein, adding, “The clocks in the steeple of the Second Congregational Church were donated in 1886 by the [widowed] Mrs. Elizabeth Millbank and in appreciation because seemingly everyone in town used those clocks.”

E.C. Benedict

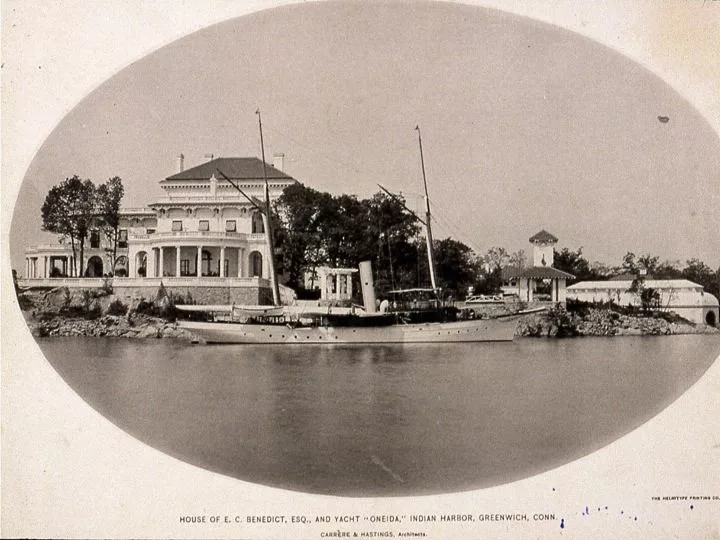

By 1895, Strackbein told, “Greenwich had become a rural oasis for new urban millionaires like Elias Cornelius Benedict… E. C. Benedict married Sarah Hart of Greenwich in 1862, and he settled on Putnam Avenue across from today’s Greenwich Library.” But Benedict was a yachtsman with a passion to live shoreside. To accomplish that he purchased then demolished the Indian Harbor Hotel, “a shorefront summer rendezvous for many prominent New Yorkers.” And built his “Indian Harbor” house as seen from Steamboat Road.

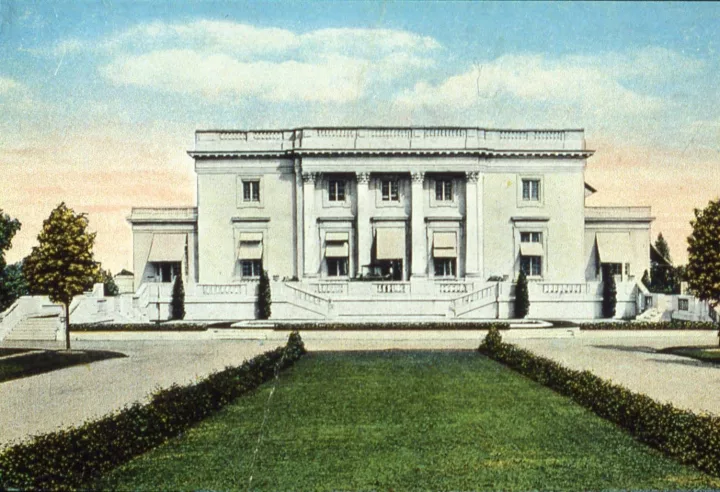

His entryway included “a 500-foot-long avenue of tall cobbler trees as seen from the steps of the mansion. One of them bore a brass plaque, which read planted by U.S. President Grover Cleveland. They were very good friends…The other side had a plaque as planted by Andrew Carnegie.” The 30-room Beaux Arts mansion built in 1895 was designed by Thomas Hastings of the New York Public Library fame. “The design was a showplace of country life, emulating the best features of European houses. Visitors would enter by this long flight of granite steps with handsome balustrade on either side, enclosing sunken flower gardens.”

“But if arriving by yacht,” described Strackbein, “guests would dock along the shore where Benedict’s yacht, the Oneida would be moored. Sailing his steam yacht was Benedict’s favorite pastime. He was a member of six yacht clubs and had sailed the world on one of his two 200-foot steel yachts.” With Benedict’s daughter Helen marrying architect Thomas Hastings, there were 800 guests who attended their marriage here at the Second Congregational Church…and the couple were photographed departing for their honeymoon on the yacht Oneida.”

Conyers Manor

Up next was Conyers Manor. “Edmund Cogswell Converse (Conyers is the old English spelling for Converse.) was drawn instead to the beauty of the rural land in the north of Greenwich to build his self-sustaining country estate in 1904,” began Strackbein. A Boston native, “he was credited with having shaped the course of American business… In his leisure moments, he created one of the greatest estates in all of New England… Converse’s estate comprised 603 acres of land off North Street that included 40 outbuildings with over 200 employees and 22 servants in his home.”

“Entering the [52-room] mansion, one would enter the era when European travel and amassing collections of European artworks reflected your social standing. “The entry boasts a Remington bronze statue and a full suit of armor of which you might see in the Metropolitan Museum of Art…On the second floor in 1908, Converse had an opera staged in this room for his 40 guests…off the main living room was a second story flower garden lined with grass paths. From here, the Converses could view the estate to the south to the west, featuring a central formal garden and reflecting pond.”

With Converse dying in 1921, he had envisioned his manor “would remain a country home and gentleman’s farm. But it would be ravaged by fire in 1985 and not be developed until Peter Brant stepped up and divided the property into 10-to-20 lots, shared Strackbein. Brant would also transform a surviving cold storage barn into a Brant Art Center in 2009 to house his private collections.

Khakum Wood

But returning to 1908, Greenwich “continued to entice millionaires to its rolling countryside” such as famed New York architect, Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, “locating his 177-acre hilltop estate on Round Hill Road in an area which we now call Khakum Wood.” Marrying Edith Minturn, daughter of a shipping magnate, her parents gifted their portrait by John Singer Sargent, now in the Metropolitan Museum. “For the Stokes, their new country estate (High-Low House) would architecturally include both a house and a castle…the stone portion of the main house, which was a castle and the half-timbered portion on the right.”

That half-timbered portion was actually a 16th-century Tudor manor house Stokes had espied in an English Country Life magazine slated to be demolished. Stokes would import the house from England in 688 cases to be restored to its original Tudor decorative elements with leaded glass windows and heavy beam ceilings. Sadly, “in 1945 the house was demolished and replaced with a more modern structure.”

Perhaps today, “one of the most visible, iconic examples of classical revival in Greenwich can be seen by residents and commuters on North Street,” told Strackbein. That Petit Trianon copy from the gardens of Versailles was “the brainchild of Laura Robinson when she was single and 38 years old…The estate was called Northway, being on North Street.” It began with a mortgage on the property in 1910 taken on by her mother and two sisters as the future site of Laura’s dream home. “It took three years and $1 million with the permission of the French government to complete the construction and interior design of Northway.”

Laura would marry a prominent New York attorney, William A. Evans, have a son who tragically died age 23 years, with husband dying of grief a month later. Dying herself in 1964, she left the house “to both Christ Church as an endowment and memorial to her parents and to Greenwich Hospital as a memorial to her husband and son.” In 1967, Renee Anselmo would purchase the site and restore the mansion, the grounds and the outbuildings.

But the 1920s marked the ending of the era of the Great Estates concluded Strackbein. “The titans of industries all died in Greenwich. It brought zoning to Greenwich and a proliferation of subdivisions… Rockefeller’s Deer Park, Percy Rockefeller’s Rockwood Lane, Benedict’s Indian Harbor, Phelps Stokes’ Khakum Wood, and Millbank’s Millbrook.”