By Anne W. Semmes

Across the U.S concerns about the effects of highly toxic “neonicotinoid” pesticides on birds and insects has led to legislation in several states outside of Connecticut. The move is on in Connecticut to push legislators to address that “new DDT” chemical pesticide threat. Last Thursday the case was made before 75 at a Pollinator Potluck meeting at Greenwich Audubon.

In her introduction of speakers Rochelle Thomas, Audubon executive director, cited her board director Kim Gregory “for making these Pollinator Potlucks happen.” First speaker Louise Washer was introduced as co-founder and board member of the Pollinator Pathways movement. “She serves as facilitator of its Pesticide Policy Committee. She worked to help pass the Birds and Bees Protection Act in New York last year and is an organizer of Connecticut Pesticide Reform (CPR), a coalition of conservation organizations and individuals working to advocate for organic land management policy in Connecticut, including immediate restrictions on the use of neonicotinoid pesticides.”

Walsh noted a “New York Times” news report in 2017 for triggering the creation of CPR. “The Germans did a good job of keeping track of flying insects since 1989,” told Walsh. By year 2017, “they’d seen 76 percent decline in all flying insects.” That report had resonated with Washer as a Norwalk resident heading up the Norwalk River Watershed Association and having helped start up Pollinator Pathways. “We were all seeing fewer insects on our windshields” and “bumble bee species are down 96 percent…We heard a lot about colony collapse with honeybees, which all raised the alarm.”

“Threats to pollinators, loss in fragmentation of habitat, that’s huge,” said Washer. But for this talk, “Pesticides and lawn chemicals are our focus,” and “The connection between pollinators and insects and birds is a really strong one.” She asked, “Does anybody know what percent of terrestrial birds rely on insects to survive?” Ninety percent was an answer. “That’s pretty good, its 96 percent.” And “We’ve lost three billion birds in the last 50 years.” And “The birds that rely on insects are the ones that have declined…So, what can we do to protect pollinators and birds – plant pesticide free native plants.”

“Tonight,” she continued, “we’re going to focus on what we can do to support state policy that restricts the most harmful pesticides that we’re seeing in our environment here…If you’re going to use a [pesticide] product, look at the label. If your lawn company is going to use a product, have them take a picture of the label and Google what it is because there are some things that are going to be really harmful.”

In the US,” she told, “we still use a lot of pesticides that have been banned in Europe, for example, neonicotinoids…banned in Europe for all outdoor uses since 2014. They’re used mainly in Connecticut to kill grubs on lawns and used in agriculture on coated seeds.” Neonicotinoids or neonics have been found “a key cause of the decline in monarch butterflies,” she said, and she cited the EPA as being “far behind on all their analysis of neonics in the environment.”

“These neonics also have terrible impacts on aquatic life…Neonics are toxic to birds even in small quantities.” And when a corn seed coated with this pesticide, “grows up into the plant, the plant itself becomes poison to insects like the leaves, the pollen.” And a single seed “is enough to kill a songbird.”

Washer added, “We’re seeing that neonicotinoids are not safe for people either. They’re being so overused; they’re getting into our groundwater.” Studies over the last 30 years, she said “show that they cause harms, especially to children.”

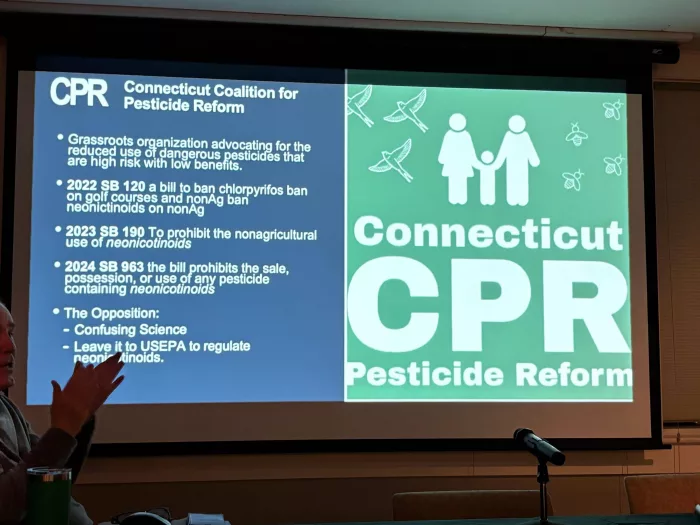

Joan Sequin was up next, as an “active member” of the Connecticut Coalition for Pesticide Reform (CPR). “She also co-chairs the land and water sector of the Greenwich Sustainability Committee,” shared Thomas, “and she’s a member of the Greenwich Pollinator Pathway.” Sequin first gave the history of CPR. “We formally came together in 2022 to pass legislation on neonics and to ban its use on non-agricultural settings, which means mostly lawns and turf.”

There was success in banning some toxic pesticides but not with neonics. Things came to a head in 2024 with the Senate told Sequin. “The Senate actually introduced their own language to regulate neonics. And unfortunately, this language wasn’t ideal…The opposition was claiming that the science behind banning neonics and trouble with neonics was debatable and confusing – that they should leave it up to the EPA to deal with.”

So, “CPR decided to turn our attention to researching and compiling our own collecting of neonic data in Connecticut,” said Sequin. The challenge was, “Connecticut DEEP doesn’t have a surgical platform that allows you to track where, when, and how much pesticides are being applied in our landscape. We focused on water quality,” and “since neonics dissolved easily in water when you’re finding them in our watershed, it’s a clear indication that they’re being applied to our surrounding landscapes.” Thus, “Are these neonics finding their way into our drinking water systems?” Of 218 pesticides sampled for 30, only neonics were showing up in the river “above federal benchmarks.”

UCONN’s Center for Environmental Science and Engineering would step in and report, “that water quality monitoring shows that neonics frequently and consistently appear in Connecticut surface waters at levels expected to cause significant harm to the state’s aquatic ecosystems, and which also represent the potential for human health problems.” And “Neonics are increasing through time…And this persistent exposure suggests near constant stress on our aquatic insects throughout all life stages…. And fewer bugs mean less food for fish and birds.”

For why they cannot wait for the EPA “to regulate neonics and why we need to do it at the state level,” Sequin brought back Louise Washer. “The EPA is so under-resourced when it comes to addressing all the chemicals that are coming into our environment,” she said. “They are completing less than five percent of their pesticide annual registration review. And we’ve been waiting for years for them to act to review neonics and we don’t know it’s going to ever happen.”

Thus, “We have to really act at a state level…We’ve come up with a group of really smart, amazing partners to think about what the best way is to take action at the state level that won’t harm farmers and landscapers or make the least burden on them.”

Washer then passed the microphone to Robert LaFrance, Audubon Connecticut Director of Policy. “My role is a little bit of a diplomat” he began, and with Washer and Seguin planning on presenting a bill at a public hearing, “we’re going to testify in favor of that.” He then asked all present, to reach out to a member of the General Assembly, “whether it’s your State Senator Fazio, or any number of other folks who are state representatives here…and tell them that this is an important issue to you and then explain why. We’re trying to get them to enact a law that prohibits the use of neonicotinoids.”

“We’re going to give the industry some time, to not actually have to implement it until 2028 or 2029, giving them the opportunity to move from that particular type of pesticide to something else…So, we think that’s a very balanced approach. That public hearing will then go to a vote to get the bill out of the environment committee. And “If you know legislators who might be able to have an impact… that’s going to be really helpful to our cause. It’s one thing we can do all together to bring our voices to the General Assembly in Hartford.”