By Anne W. Semmes

To kick off this celebratory 250th year of America’s founding the Greenwich Historical Society, with its ongoing exhibit of “Greenwich During the Revolutionary War” presented a riveting talk before 82 attendees by Dr. R. Scott Stephenson, the president and CEO of the Philadelphia-based Museum of the American Revolution. Stephenson has for over a decade helped to enrich and develop the Museum’s educative message and collection. His description of George Washington’s vigor and sacrifice throughout the Revolutionary War took center stage.

So, its 1775, and George Washington, at age 43, has arrived in Philadelphia commissioned “as commander-in-chief of the armies of the united colonies of America,” begins Stephenson. “So, we are fighting to protect our rights as English citizens, but Washington has to try to turn this ragtag militia into an army,” with some 40,000 New England soldiers “who had bottled up the British soldiers,” in their first major and successful military campaign in the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

Washington arrives wearing a uniform he has created, “but not with the expectation that he was actually going to set out and have to go to war.” Thus, he promptly writes a letter to wife Martha with his news that he is not returning to Mount Vernon, “that duty requires me,” he writes, “to go lead the country to restore its rights.” (This letter being one of the “most effecting letters” of only three letters of the couples’ correspondence not burned as so designated by Martha at her death. He encloses a “beautiful piece of silk” as an apologetic gift. Washington would return only once to Mount Vernon in his eight years as commander.

With Washington’s signing on the consequence is he brought no camp equipment with him. A request goes out to Congress to assemble the camping gear he would need to “take to the field as commander-in-chief.” But Washington is credited with purchasing a “set of marquees, two large circular, oval-shaped tents.” Stephenson shares a period engraving of “a large dining marquee…about 22-feet long, about a dozen feet tall… It’s a big open area where you can set tables, have meetings, His slightly smaller sleeping and office tent…has a side entrance as opposed to an end entrance. And this was the only private space that the first Commander-in-Chief of ours had.” Yes, for eight years!

“There’s a theme I’m going to hit on until you all remember it,” notes Stephenson, “and that is Washington remaining among his troops.”

Commander Washington had “a political role as well…to try to get Congress to support the army, but also to teach the soldiers the cause that they were fighting for.” But he needed to distinguish himself before his soldiers “who all dress alike…And nobody knew who he was. So, he purchases this ribbon.” It’s there as part of his uniform in a well- known painting Stephenson shows of Washington by Charles Willson Peale to hang in Philadelphia’s Independence Hall.

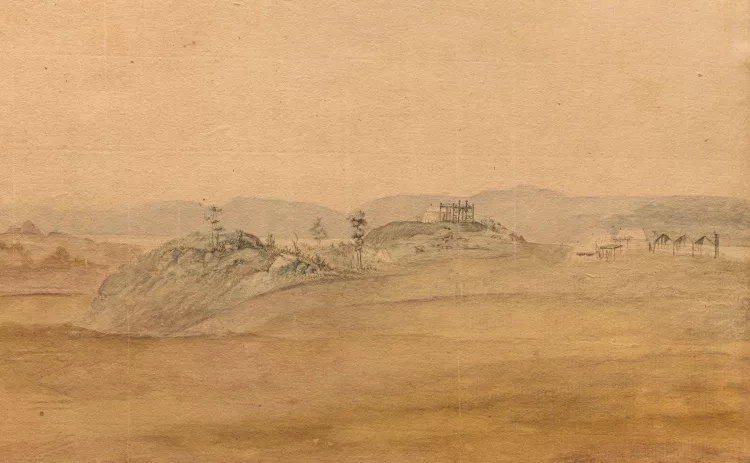

What else became impressive to those soldiers was, “to be able to say they had actually conversed with General Washington at his tent.” Proof of that tent became a 10-year search of Stephenson in his work of developing his Museum. “No one had found an eyewitness image of Washington’s tent during the years of the Revolutionary War.” But a panoramic watercolor landscape seven-feet wide pops up at an auction. “It’s a scene of the Revolutionary War. It says Verplanck’s Point. It’s in the Hudson Highlands,” and its now in Stephenson’s Museum.

“What you’re seeing are tents that are set up off in the background with all kinds of strange structures around them.” “What really hit me over the head,” he says, “there were some officers tents, and you see the one that’s up to the left, on that little mound with what looks like a jungle gym in front that is actually an arbor of greenery to provide some shade. This is late summer of 1782. And that marquee unlike every other one in the entire image, has an entrance on the side, which is exactly like George Washington’s!”

Stephenson then shares a French soldier’s observations from his diary of that scene remembered. “Washington at the beginning of this encampment,” he wrote, “was on the point of taking a house for his headquarters, sleeping in a house, but he decided to set an example to his soldiers by living in camp.” “But by placing himself upon that hill,” says Stephenson, “the very first thing that 8,000 veteran soldiers saw when they crawled out of their tents in the morning was that their commander-in-chief was there with them living under canvas. And the last thing they saw as they crawled in at night before lights out was the candle still burning up on that hilltop.”

Stephenson shares a portrait of Washington painted by the American artist Joseph Wright. “Washington sat for that portrait in November of 1783 in the last encampment of the colonial army before riding South to resign his commission…Washington himself considered this ‘very like, but not flattering,’ which means it probably really does look like him.” Washington is white-haired and stout.

“I think you can see what living under canvas for twice the length of time of the American Civil War did to our first commander-in-chief.”

He tells a final tale. “So just in the northern part of the Hudson Highlands in March of 1783, the army had been unpaid in some cases for years. The officers who had suffered wounds, suffered illness – there was no guarantee of any kind of pension, any kind of future there. And Washington got word of this gathering. And you can imagine how they felt when the old man actually showed up and probably a few expletives were whispered to one another.”

“And Washington came up to the front of the room to address the soldiers. ‘I have never left your side,’ he said. ‘And I’ve shared in all the hardships with you.’ He then pulled from his pocket a letter he’d received from Congress making promises that there would be some relief coming. Those soldiers then saw him do something that none of them had seen before.”

With few knowing Washington needed reading glasses, other than his valet, William Lee, long living with him in that tent, “He pulls out of his pocket a pair of spectacles, and says, ‘Yep, I never left your side one moment. I’ve been the constant companion witness to your distresses. I have not only grown gray, but almost blind in the service of my country.’ And the eyewitnesses there, literally men who had charged into the mouths of cannon, wept like children.”

“And with that act,” Stephenson concludes, “Washington saves the republic at one of its most vulnerable moments. And it is why when I look at that tent that’s at the Museum of the American Revolution, it’s not just an artifact of our founding father, it’s not just a military artifact. It is the moral authority that Washington had at that moment that came from him living under the canvas for all those years.”