On my watch – Grant Gregory Sr. Introduces Whooping Cranes at Greenwich Audubon

By Anne W. Semmes

Greenwich’s Grant Gregory Sr. is a nature lover. His GlenArbor Golf Club in Bedford Hills, N.Y sports a myriad population of bluebirds. In 2016, Grant and his family were honored with Audubon Connecticut’s Environmental Leadership Award for their “passion for wildlife, habitat protection, and the experiences derived from a life that involves nature.” Now add to that passion, the love of cranes. And it just so happens that my wildlife photographer, Melissa Groo opened the door to that new passion, urging Grant to visit the extraordinary spring migration site of Sandhill Cranes in Nebraska that she attends annually as hosted by the Crane Trust.

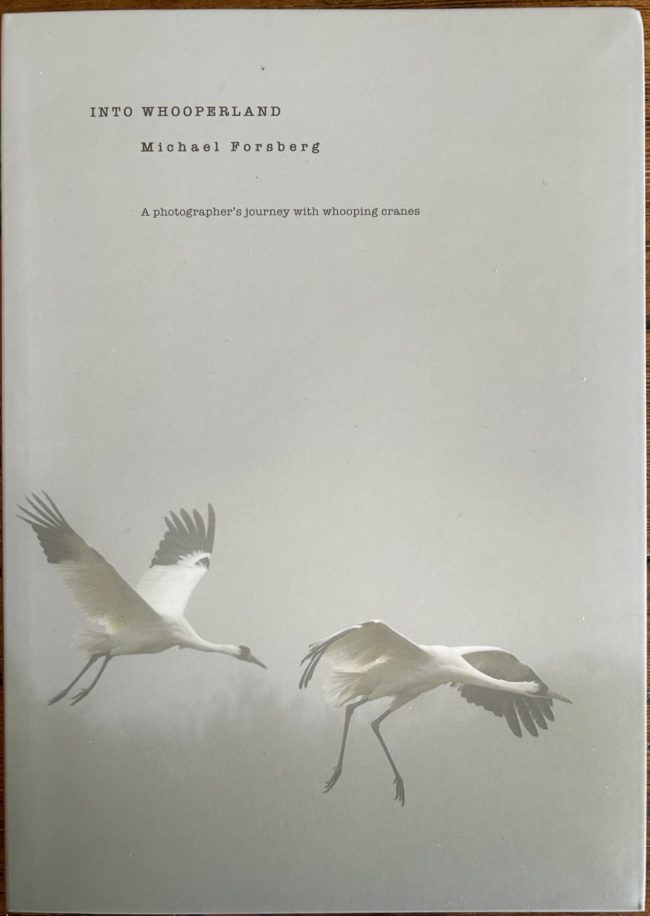

During Grant’s memorable visit he had met up with distinguished photographer of cranes, Michael “Mike” Forsberg, and invited him to come to Greenwich Audubon to speak on his new book “Into Whooperland” of his discovery of the even rarer whooper crane species.

Invited to this Audubon event that took place on October 29, were officials of the Crane Trust, my daughter, and a host of crane enthusiasts including Heather Henson, daughter of the late puppeteer Jim Henson, and John Nelson who came to live in the storied Henson family house in Greenwich. Also present was event organizer, Marty Cannon, Greenwich Audubon executive director Rochelle Thomas, and Sabine Meyer, photography director of the National Audubon Society, along with other persons involved in creating Mike Fosberg’s exquisite photo-filled book, “Into Whooperland.”

“It’s hard to describe in two short days the immersion and the experience, the sound, the entire environment and the hospitality,” Grant began in his introduction, touching on his experience in Nebraska, and of meeting up with Mike. “He’s at the University of Nebraska as a professor, and I actually went to the University of Nebraska,” Grant shared. “Mike’s a prolific writer, historian, world-class photographer and renowned storyteller.”

So, before some 60 crane lovers gathered in Audubon’s Melissa Groo Gallery- now no more with her photo prints taken down, Mike’s story would unfold how he was led to his discovery of whooping cranes via sandhill cranes. And it was Mike’s aha moments that stood out, as the photographs behind him illustrated his story.

“So, if you come to the Platte River and you’re going into a blind in the morning, this is what you’re going to see. You’re going to be all bundled up and have a heater there, which would be nice. But you’re going to look out and you’re not going to see anything. And then the light is going to start to come on. You’re going to see that thin line of red on the horizon…turn a million shades. And then you’re going to see sandhill cranes on the river and start to hear them…almost like a symphony starting. It’s just one note here and then a couple more notes and then more and more and more until it rises in this great crescendo.”

But it was at that moment, “as that light was coming on, there was another bird that lifted up out of that sea of gray,” he told. “It throws up heads and shoulders before the rest.” He’s seen his first whooping crane. “This is one of the most powerful moments that I’ve experienced. They’re the tallest bird in North America. They stand five feet tall – and taller if you piss ’em off, with an eight-foot wingspan. And they’re beautiful… with their black-tipped white wings.”

“So, like all cranes [15 crane species worldwide], they’re very long-life cranes. They live 20, 30, 40 years in the wild.” The very oldest crane to have lived in wild or captivity he told was “a Japanese Crown crane in the Royal Court of Japan that lived to be 82 years old.”

“Besides being tall and long-lived,” he continued, “they only have two young a year… and usually only one of these birds ever survives that first year. So, their populations can drop like a rock really quickly.” And “They don’t reach sexual maturity until they’re four or five.”

“The core of their nesting range,” he continued, “were the tall grass prairies in the northern Great Plains and the upper Midwest. And they would winter as far south as the Texas Gulf Coast, and even over in the Carolinas.” But along that route there was historically a “wipeout near Elm Creek, Nebraska, along the Platte River. These birds were market hunted…for parlors and for egg collection and everything else.” But now, “There’s slowly and not so quietly anymore a movement to bring nature back into our lives again.”

A campaign commenced, “Don’t shoot these white birds…. The whooping crane postage stamp came out…In 1973, the Endangered Species Act was passed, and these birds were one of the first creatures listed.” And in 1973, “The International Crane Foundation was formed. So, Dr. George Archibald, co-founder with Ron Sauey were both Cornell graduate students at the Laboratory of Ornithology…And they are champions of the 15 crane species in the worldwide today. And Heather Henson here has been on their board. She’s helped out so much throughout the entire crane world. They’re found on five continents, except for South America and Antarctica.”

Mike then took us on a small plane flight following the whooping crane migratory path 2,500 miles from their wintering grounds along the Texas Gulf Coast to their summer nesting grounds in the Wood Buffalo National Park in Alberta, Canada. “I had the opportunity again to work with researchers doing exciting research…putting remote cameras and acoustic recorders near the nest of whooping cranes… And you can see here two whooping cranes …when they have a threat posture that looks like a vampire, they can get their wings really big, and they stand very tall, and they just move towards you.”

With two chicks in the nest, the difficulty was to see “what these birds were eating.”

“So, this chick survives on its yolk sack for the first day of life, mostly for nutrition.” The camera then zoomed in on the first feeding of a dragonfly larva. “Dad’s a little rusty here, having not done this in a year…There we go. The parents are celebrating. Oh my God!”

“So, this little bird will grow in about three months to be two thirds to three quarters the size of mom and dad, and then make that flight just like the sandhill crane. The story really is these birds are a conservation success story. They were nearly gone. In the 1940’s there were less birds in the world than there are of you in this room. [The whooping crane population fell to fewer than 20 birds.] And now they’re coming back and there’s over 500 now in the wild flock. So, whether or not these birds continue to become a conservation success story or not is completely dependent upon us. They’re a lot more resilient than we think, but they continue to need our help.”