By Clay Kaufman

When my eldest daughter was in 5th grade in public school, she and several other students apparently finished the “project on an animal of your choice” faster than other students, and had nothing to do with a few days left in the project. So each of them were told by the teacher to pick a second animal and do the same project again. And then a third animal. Not surprisingly, my daughter came home complaining. I sympathized with the teacher: many members of her class of 27 students simply needed more time. The situation prompted me to think further about enrichment and acceleration, and how best we can challenge students.

Students learn at different paces, and as parents, we certainly see the differences among children within our family. Those of us who are educators witness the same challenge: how to support all students while engaging students at their appropriate level. A wise educator once shared with me his eternal struggle. “Parents want homogeneous classes,” he said. “When you have one student, you have a homogeneous class. But the minute you add a second student, you no longer have a homogeneous class.” He was right. Two students rarely learn at exactly the same pace. He also acknowledged the reality that students will not be alone in class, and in fact will often benefit from learning in groups. So what do we do?

There is a delicate balance between enrichment and acceleration. One might define enrichment as the layering of challenges within a particular assignment. For example, in a middle school English class in which students have to write an essay, the basic requirement might be a five-paragraph essay with an introduction, thesis, conclusion and three examples. How might you enrich that assignment? Some students might pull basic examples from the text. Other students might be ready to choose quotations from the text to incorporate into their essay, and then analyze them. For a strong student who is an eager reader and already proficient in writing an analytical essay, the teacher might have the student choose a second book–or even a poem–and write a comparative essay. In math class, where elementary students are first learning about the area of a triangle, rectangle and other basic shapes, students who need enrichment might find the area of a rectangle with a triangular hole in the middle, or with a semicircle carved out. There are many possibilities.

It is helpful for teachers to be able to focus on the same unit with all of their students, so enrichment becomes useful and necessary. Good professional development opportunities help teachers find resources for students, and these days teachers all over the country–who are all looking for enrichment activities for exactly the same topic–are sharing their best ideas, all in the name of helping students do their best.

Sometimes it is appropriate for a student to accelerate–usually in math, science or foreign language. A student who has mastered arithmetic and Pre-Algebra might be ready to take Algebra I in 7th or 8th grade. Not all students need to take Calculus in high school, however, so how do you decide whether a child is ready to accelerate? As parents, we all know how our heart sinks when our children come home from school and say “that class is boring.” That might be a sign that they need enrichment or acceleration. Of course, if your child comes home from the first week of school and says “I already know this math,” that’s usually just a sign that the teacher is reviewing key topics early in the year. But I see two kinds of students who benefit from accelerating: a) students who mature, well-organized and capable and whose curiosity can be stimulated by moving more quickly and b) bright students with a great knack for the topic who may not be employing all their study skills and might still be a bit squirrelly, but who rise to the occasion when placed in a class with older students. Acceleration is certainly appropriate in many cases.

When does acceleration backfire? In my experience, when “acceleration” means racing through topics without going into depth, just to have “covered” the material, students don’t benefit. Some summer programs promise a “full year of Algebra in 3 weeks,” which is usually ineffective and leads to struggles in higher level math, when students don’t have a strong foundation in the material.

As parents, we want our children to feel engaged and challenged without being overscheduled. Sometimes after school activities can be an effective way to engage our children, such as a programming class, but students are busy during the school year already. Summer enrichment programs that cover topics not usually taught in school can therefore be good ways to challenge a child. Applications of math or science, such as engineering, space science or other areas can be fun summer activities. In school, it is fair to ask if there are ways that a teacher can enrich the curriculum for our children, recognizing that we all–including the teachers–want our children to be curious, happy and challenged. Teachers are generally desperately trying to reach the same balance parents hope for. We are all in this together. Often an effective way we as parents can help ensure that our children are getting the enrichment they need is to teach them to be effective self-advocates. Although there are times when a parent needs to ask, when a student approaches a teacher and asks for an extra challenge, it can feel less intimidating than when a parent asks, and it teaches the student a good lesson.

Again, we are all in this together, and I have always appreciated it when a student or parent has approached me with a question or a problem (as opposed to a demand): “this is what we are seeing; is there anything we can do together to make things work better?” When we empower students, and when schools and families work together to ensure that each child’s experience is enriched in its own way, it’s a win for everyone.

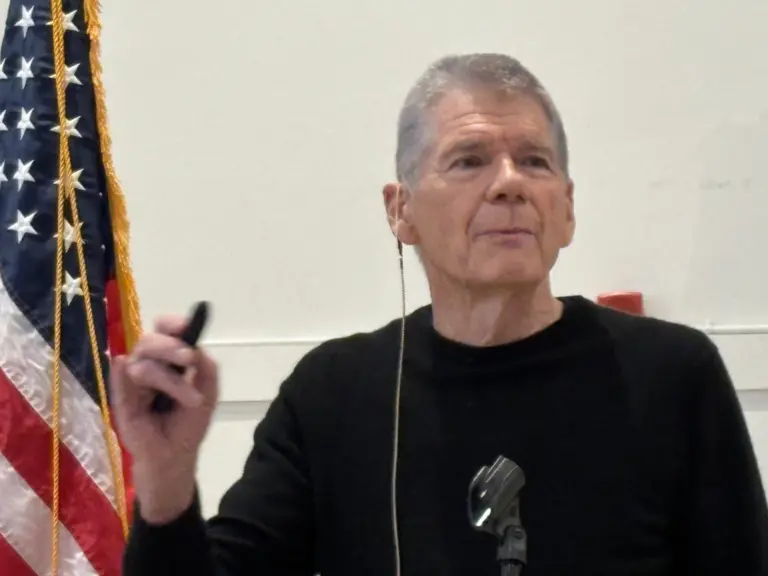

Clay Kaufman, a longtime educator and school leader, is founder and Head of School at The Cedar School, a high school for students with language-based learning differences, such as dyslexia, here in Greenwich.