By Anne W Semmes

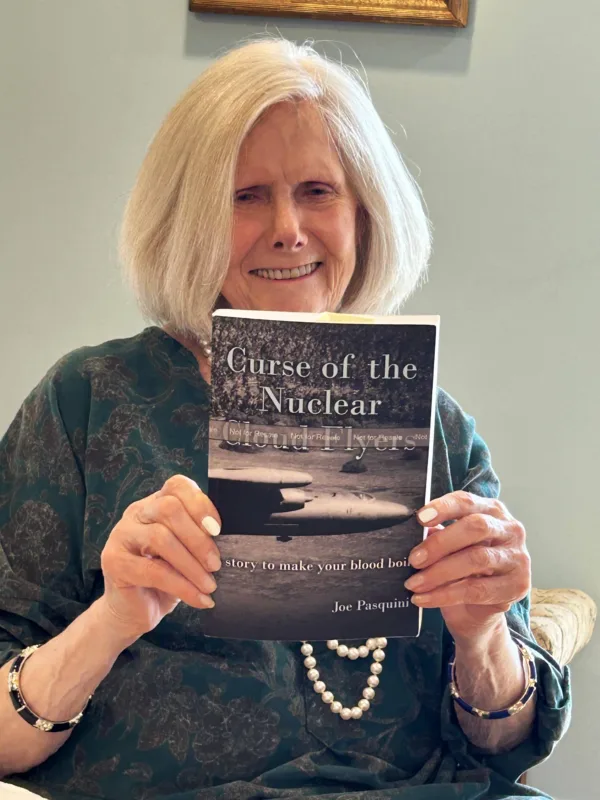

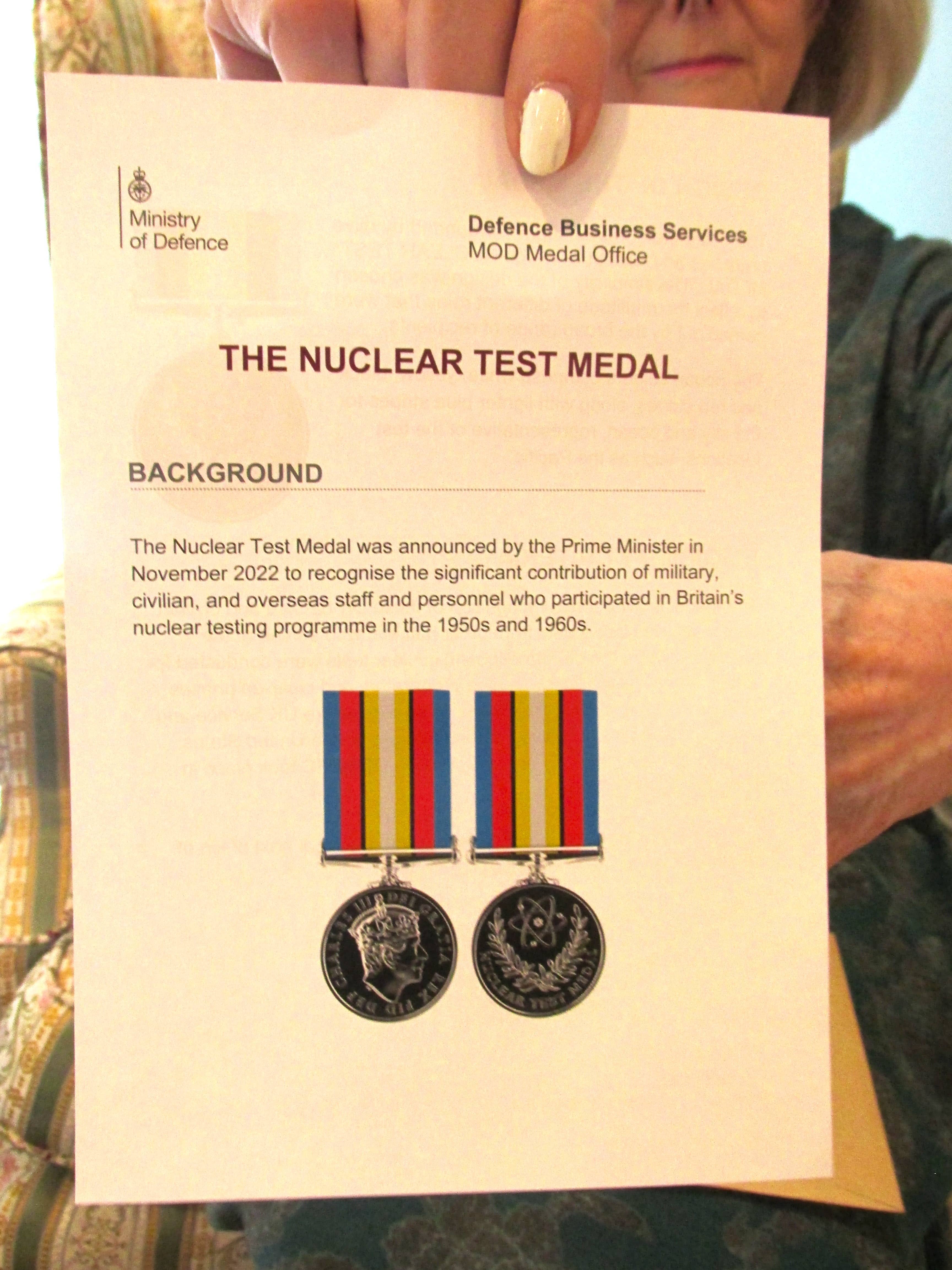

Roberta Pasquini now in her 80’s has lived an extraordinary life of a beloved family, but also of extraordinary pain experienced by her late husband, Joseph Pasquini, who survived flying through the mushroom cloud of a hydrogen bomb dropped by the British in 1958 over Christmas Island in the Pacific. Her husband, who served as a navigator in the Royal Air Force (RAF), lived to tell the tale in his book, “Curse of the Nuclear Cloud Flyers” he published in 2020, then died in 2022, age 88, of cancer he had endured for decades. Thus, he missed receiving the British Nuclear Test Medal recently received by his widow, with King Charles depicted on the medal.

“It’s wonderful that they’re getting some recognition at last,” said Roberta Pasquini. “However, it’s really too little too late, isn’t it? It’s just a bit of tin.” Yes, after nearly 70 years the British Ministry of Defense was recognizing what those RAF Cloud Flyers and their families had endured, not to mention a reported 20,000-plus on the ground in those bomb testing years.

Mrs. Pasquini shared with this reporter her first receiving that Medal in her apartment in a retirement home she moved to after her husband’s death from their home in Cos Cob. Present with her when she opened that Medal envelope was a striking sculpted portrait of her husband. And on the coffee table was a copy of her husband’s book, “Curse of the Nuclear Cloud Flyers.” “Writing that book kept him alive,” noted Roberta Pasquini.

Pasquini’s Book Writing Years

She described some of those book writing years – over more than a decade. “He began researching some of the documents in the National Archives kept at Kew Gardens, and it was open to the public, and then one day the documents were no longer accessible. They shut the door.” Subsequent news stories state that a number of nuclear test articles, documents, archives have been removed over the years.

The basic information of those flights of the nuclear cloud flyers of the Number 76 Squadron can be found on Wikipedia [their motto was Resolute]. The official reading of the size of the bomb in the 1958 “Grapple Y” nuclear test that the crew flew through was the largest nuclear explosion created by the British at three megatons, the equivalent of 3,000 kilotons.

Joseph Pasquini was quoted years ago by the BBC of what it felt like to fly into that hydrogen cloud: “It detonated at 8,000 feet. We had our eyes closed, but even with our eyes closed we could see the light though our eyelids. It took 49 seconds for the light to stop. Being in the navigating position, I had a little window, and I watched the whole thing develop and spread and then start climbing. I think I saw the face of God for the first time. It was just incredible. It blew our minds away.”

That BBC report also notes Pasquini as having survived seven bouts of cancer with his children having had “various cancers,” and add his wife. This was too often seen in those on the ground with their generational effects from radiation.

How Roberta and Joseph Pasquini Met

Curiously, it was in that first British nuclear testing territory of Australia that Roberta and six-foot-two Flight Lt. Joseph Pasquini had met. “I met him in 1958 in Adelaide,” she shared, the city where her family lived. The young aviators on leave “would pop in and out because they were going backwards and forwards to Christmas Island. They were bouncy, vivacious, having training on survival… So, they were going to put on a good show.”

They married in 1961 in England where Joseph and his Italian family had moved to from Tuscany, Italy where his father Menotti Pasquini was a noted sculptor. With the Depression causing the sculptor to find more work in London, the family also found the Blitz. But they survived, “And back then young men had to join the forces for a number of years,” told Pasquini. “They could join for four or 12 years, and he did the 12 year one. He was trained to be a navigator.”

The first four years were spent in Germany “teaching other young men how to drop bombs,” he had shared, with “I dropped 4,000 bombs along the Russian border.’”

The Pasquini married life would eventually bring them to America in 1969, with spells in Banksville, Delaware, Riverside, and finally Cos Cob, with Joseph working as a business consultant when he was not visiting some four hospitals to treat his cancers. But the fear of those radiation ills never left him. His wife recounts a few family stories that reflected those fears.

When they were living in Wilmington, Delaware in 1979, they were not far from Three Mile Island in Harrisburg, PA. “And there was a little bit of hiccup with that power plant. And Joe reacted immediately when that became public. And we spent a week indoors, including the children and the dog. He kept track of it on the radio, the television – and which way the wind was changing.”

Then there was the day in Banksville when his two daughters came home from a party with glow-in-the-dark stickers. “And Joe came home one night and there weren’t many lights on. And there they were on the fridge glowing. And he went ballistic. Because back then, the watches had glow in the dark stuff made of tritium to make it glow in the dark. And that’s radioactive.”

“And then there was that movie that came out in the 1980’s called “The Day After.” “It was about what happened the day after a nuclear explosion. It was horrifying because it was showing everyone what happens if you survive…you’re going to die eventually of radiation. Don’t waste your time going under a table.”

“We were in Riverside,” she remembered, “And Joe had commandeered the dining room table with the map and his navigating instruments to calculate if a bomb landed on New York City, if we would survive. And he came up with if there’s some elevated hills and if there was a blast, it would kind of jump over us somehow.”

Looking for Compensation

So, coming back to the present, and that medal that Roberta Pasquini will place near that true-to-life bust of her husband, she’s asked, how does she think her husband would have reacted to receiving such a medal? “He would value receiving the medal. He would see it as a first step going forwards.” And how does she see everyone involved in that nuclear testing to be compensated? “With money, and lots of it.”

[Unlike the U. S military, the British government does not acknowledge that veterans of nuclear tests are at any elevated risk of cancer.]

So surely, there needs to be a sharing of those medical records that will show the human cost of those nuclear cloud flyers. To that end look to a website called Crowd Justice, a legal crowdfunding website, with the crowdfunder called “Bloody Truth: The Nuclear Test Veterans’ Search for Justice.” Its effort is to raise funds to engage “a top law firm to write letters, to get the protocols to sue the British government to give these nuclear veterans their medical records.” According to the website a reported 58,780 pounds has been raised thus far with a target of a hundred thousand pounds.

But Roberta Pasquini has another wish for recognition: “A big public memorial, a big public statue of the nuclear veterans that were there and now possibly have moved on. A statue where it’s visible for people to see, and then be told that this memorial is for the veterans who passed away from one illness or another.”