By Anne W. Semmes

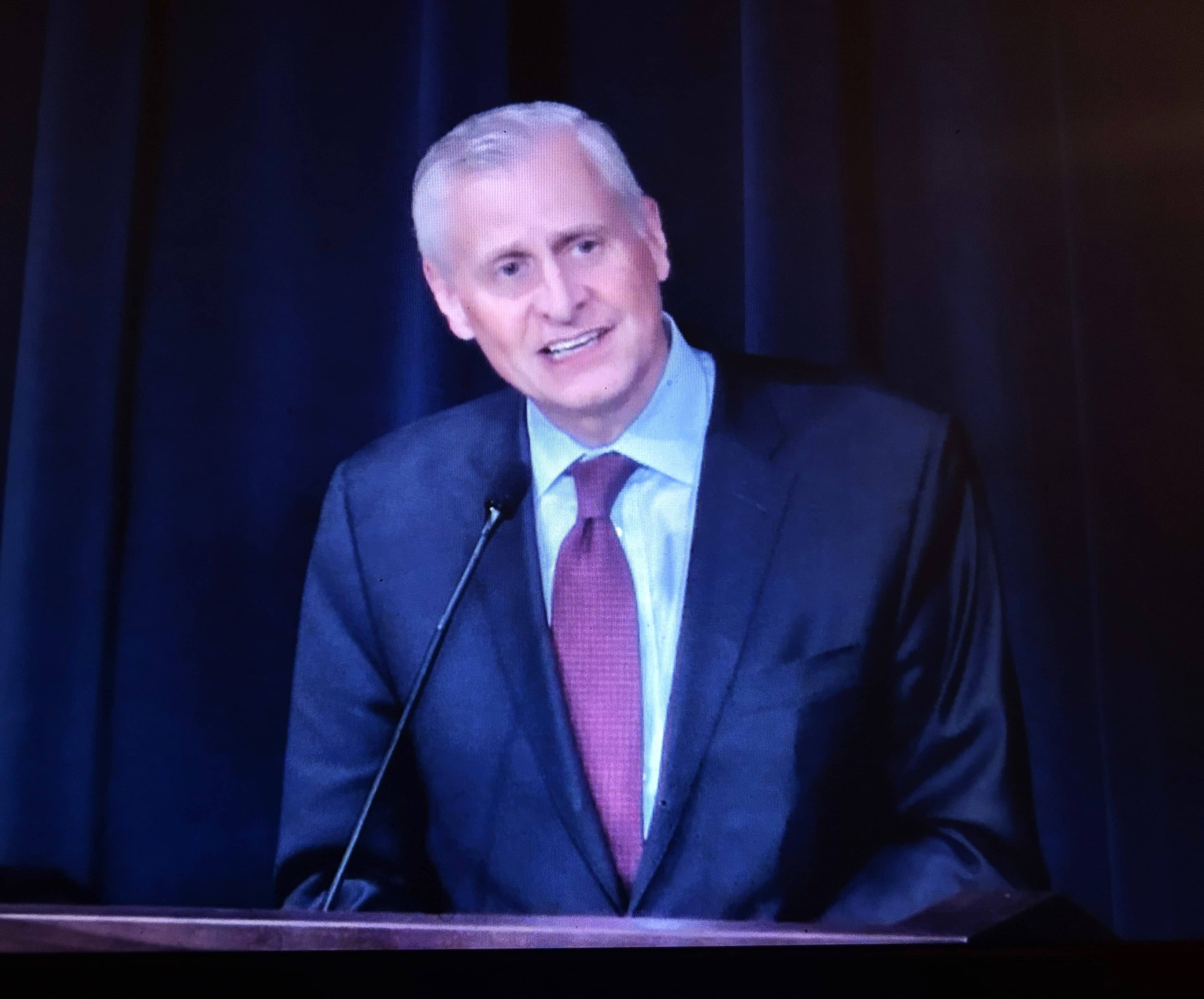

Jon Meacham is a serious historian of American presidents with a penchant for fleshing out the humanity in his famous subjects. He has a love of true democracy, and a recurring sense of humor. All of this was on display in his lengthy talk on “The Art of Leadership, Lessons from the American Presidency” at Greenwich Library a week ago Thursday evening in its Signature Series before a full house (and more on zoom) of the Berkley Theater.

Jon was introduced as a Pulitzer Prize winner for his biography of Andrew Jackson, “American Lion,” as a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, and presently serving as “distinguished visiting professor” at Vanderbilt. His next book coming out is a celebratory picture book on George H.W. Bush’s life to be published on Bush’s centenary June 12.

So Jon began with humor to counter his kind introduction for his “unique ability to bring historical context to issues and events impacting our daily lives.” He recalled years ago being approached by a woman “in a mall in Washington” saying, “Oh my God, it’s you…Your books have meant so much to me. I’m going to go buy your new book and have you sign it. Will you wait right here?” He waits and she brings back novelist John Grisham’s latest book. “So whenever, I think I’m one of America’s most prominent anything,” he told, “I remind myself that somewhere in America there’s a woman with a forged copy of “The Runaway Jury.”

But he jumps quickly into what he sees as, “This is an hour of maximum peril for American democracy.” And “The points I’m going to make do not come from a partisan place. They have partisan manifestation in this particular hour because the way the constitution developed, because of the electoral college, because of the vastness of what became the American polity, we needed two organizing parties to make the constitution work.”

“This is an hour of maximum peril,” he continued, “because one of the two major functioning parties has put its own power and its own ambition ahead of the Constitution and the rule of law. And you can walk out and be upset, but I’m a historian, I’m a biographer…I’m as politically moderate as you can imagine. I grew up on a civil war battlefield…I know from a reading of the American past that when we lose a sense of proportion, when we lose the capacity to say you’ll win some and you lose some. When we stop seeing politics as an arena of contention in which we seek solutions to problems…instead as occasions for total war, every hour of every day that way madness lies, and the republic will not survive.”

“The claim of a democratic republic like ours,” he said, “is that you give up immediate gratification. I can’t just take what you have just because I want it. I have to figure out a way to compete for it, to prepare myself to be the kind of economic actor you are, the whole Adam Smith chain of being here. That’s what democracy is because the reason it’s so important is it protects what you have while still enabling me to seek it. And if we begin to see each other, not as neighbors, but only as enemies, it doesn’t work.”

“So democracy is a counterintuitive undertaking,” he added. “If it were easy, everybody would do it. When the author of Leviticus and when Jesus of Nazareth said. ‘Love thy neighbor as thyself,’ they were commanding something because it wasn’t happening. You don’t put up speed limit signs if everybody’s driving safely.”

“Love thy neighbors is a radical commandment,” he continued. “Who wants to do that? No, thank you. I love myself and maybe I’ll be nice if it’s in my interest, but that’s not the way democracy works. It’s not the way America works at its best. And Franklin Roosevelt understood – in that the line we all remember from his inaugural address, that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself. Nameless unreasoning fear that paralyzes our advance and converts progress into retreat.

“And as John Adams pointed out,” he added, “Our constitution is designed with a governance of a moral and a religious people and no other because without a moral sensibility that we should give as well as take, this will not work.”

He then noted, “We choose to listen to extreme voices, and let’s be honest, many of us listen to extreme voices because they’re entertaining. It’s fun, it’s invigorating. Richard Hofstadter wrote about this, the paranoid style in American politics, every day is a battle of good versus evil. Every citizen is a combatant. Vigilance is vital, but obsession does not lead to rational democratic thought.

“We’re divided,” he said. “That’s fine. But it is not fine if we don’t recognize the legitimacy and the dignity of the other person. And I commit that sin all the time at the price of cleverness and glibness. I appear too dismissive of the cares of concerns of those to my right politically. And I try. I fail, but I try. As Robert Louis Stevenson said, the duty of the Christian is not to succeed, but to fail cheerfully, which is the only definition by which I’m a good Christian, but I’m aware of it.”

Jon then cites memorable words of Martin Luther King delivered at Washington’s National Cathedral on a last Sunday in Lent. “In that sermon he gave one of the greatest definitions of democracy I’ve ever heard. “I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be. And you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be. That’s the way God’s universe is made.”

“America is about ebb and flow,” Jon said. “And we have to do everything we can to make the bad stuff ebb and the good stuff flow. And as Churchill said, you can always count on us to do the right thing once we’ve exhausted every other possibility.”

This reporter will end here with adding to Jon’s fine homily on democracy, with some memorable words Jon wrote in the epilogue of his masterful 2022 book, “And There was Light – Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle.” “Abraham Lincoln did not bring about heaven on earth. Yet he defended the possibilities of democracy and the pursuit of justice at an hour in which the means of amendment, adjustment, and reform were under assault…In life, Lincoln’s motives were moral as well as political – a reminder that our finest presidents are those committed to bringing a flawed nation closer to the light, a mission that requires an understanding that politics divorced from conscience is fatal to the American experiment in liberty under law. “