On my watch – Giving Thanks at Birthday Time for 12 Green Heroes in My Life

By Anne W. Semmes

In this my birthday week I am moved to honor those who have gifted me in my love of nature across the years with their extraordinary gifts and wish to make their gifts known to my readers. My hope is that you in your life will find the way to honor your green heroes!

Ted Gilman

When I first arrived in Greenwich from New York as a young mother in 1975, I headed for Greenwich Audubon and Educator/Naturalist Ted Gilman took me under his wing and for 40 years was my guide to the natural world. I wrote him a poem once that begins: “There once was a guide called Ted/ Who inspired everyone that he led/Into the wilds he’d take you by hand/And introduce you to nature as a magical land./Didn’t matter to him what season, day or night/With sights and sounds he brought his students delight/“What’s it doing here, and why?” he would ask./ Making us aware of nature was his endless task.”

Scott McVay

The wonderfully curious Scott McVay came into my life perhaps at the Poetry Festivals his Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation put on that he headed. I know that as an English major at Princeton Scott fell in love with “Moby Dick.” So, when a scientist came to Princeton in 1961 to talk of how bottlenose dolphins appear “to possess a level of cognition and awareness” he joined that scientist in his research to teach a particular dolphin astonishingly “how to speak English.” He would then partner with Roger Payne in the discovery of whale song as a chorus of “exuberant, uninterrupted rivers of sound.” The two would each do their best to bring an end to the killing of whales worldwide. In the book “Mind in the Waters” that Scott contributes to, he kindly signed it, “To Anne Semmes who is on the trail of discovery and who is likely to share her insights.” I’m trying to, Scott!

E.O. Wilson

It was at Yale University after his talk that I first met the great biologist and “ant man” E.O.Wilson. “Did you say your last name is Semmes, of the Admiral Raphael Semmes of the CSS Alabama family?” “Yes,” I replied, then learned of his great-grandfather, William Christopher Wilson, a Civil War blockade-runner. That connection led to Ed naming his character Raphael Semmes (Cody) in his only novel, “Anthill,” after asking me my family permission! I would visit Ed in his Harvard office, write about him – as one of our country’s greatest scientists of the natural world, and be invited as the only journalist to that most extraordinary gathering of scientists to discuss Ed’s theory of the Biophilia Hypothesis at Woods Hole, MA in 1992. The idea that we can trace to our very genes our love of the natural world and all its diversity comes from Ed, God bless him, gone now two years from our world.

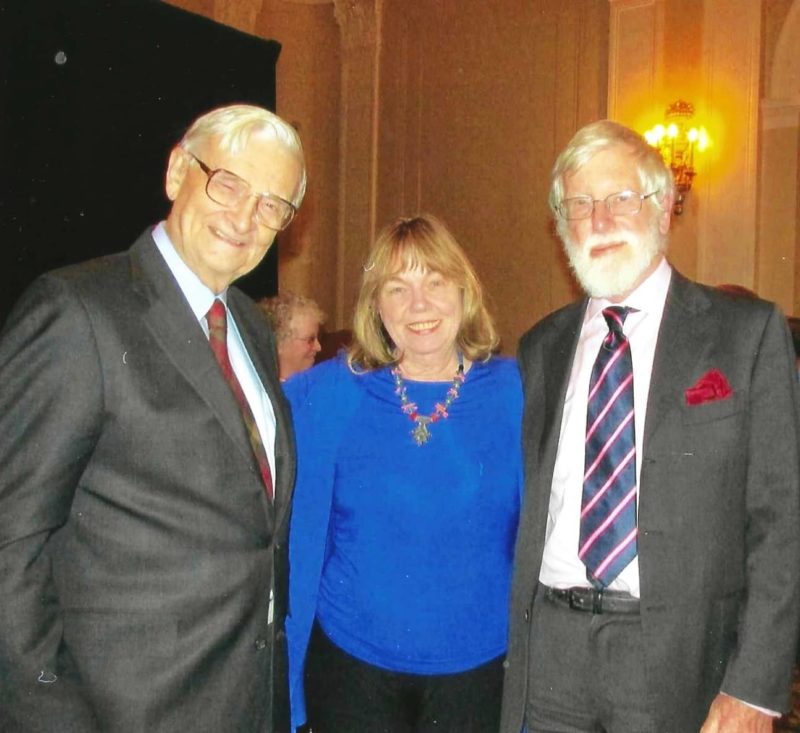

Sir Ghillean “Iain” Prance

Botanist-ecologist Iain Prance opened the door to the Amazon for me in a talk he gave on the Amazonian rainforest in the late 1980’s at what was the Greenwich Art Center. Iain was then Senior VP of Science at the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) before becoming Director of London’s Kew Gardens in 1988. Iain’s fascinating fieldwork in the Amazon region of Brazil triggered my desire to go to the Amazon with his help. So, I joined a group in 1991 for a river cruise on the Rio Negro with other NYBG staff members and the director of Boston’s Arnold Arboretum. We also visited a research camp outside of Manaus. A life-changing experience. I later enjoyed a memorable visit with Iain at his new job at Kew. Iain had a formative hand in the creation of the world’s largest indoor rainforest – the Eden Project in Cornwall, that I plan to see one day.

Dr. Tom Lovejoy

Ecologist and biologist Tom Lovejoy graced Greenwich with his visit in 2020 – a year before he died – to be honored with Audubon Connecticut’s Environmental Leadership’s Award. I met Tom many years ago in Washington without knowing I would venture one day to his extraordinary Minimal Critical Size [Rainforest] Project outside Manaus in the Amazon that he created when serving as VP for Science of the World Wildlife Fund – US. It has served as a lab for conservation scientists – count Ed Wilson and Iain Prance – and a classroom for students to experience rainforest biodiversity. Early on Tom was inviting to the study site called Camp 41 U.S. Senators, Congressmen, other game changers, and the occasional journalist, such as this reporter to experience in its small clearing, hung with a few hammocks, how the Brazilian Amazon is “the lungs of the planet.”

Scott Mori and Carol Gracie

On my 1991 Amazon visit, it was an honor to travel with tropical botanist Scott Mori, Curator at the New York Botanical Garden. Traveling with him was his artist wife, Carol Gracie. The two had explored so many rainforests in so many countries, with Scott fearlessly climbing tall trees to search out possible new species. He was ecstatic seeing new plants. Evenings aboard our boat on the Rio Negro Scott would lay out his finds while telling us of the many different fireflies, how you could identify them “by their different lighting rhythms.” Carol would take glorious photos of flowers. I cherish a large portrait of a passionflower she took. Working for years with his director Iain Prance, Scott would retire as Nathaniel Lord Britton Curator of Botany in the Garden’s Institute of Systematic Botany. Sadly, both Scott and Carol have left our world.

H. Bruce Rinker

Perhaps it was Tom Lovejoy who led me to Bruce Rinker, the Pied Piper to the Rainforest Treetops. Tom had attended the boarding school at Millbrook, N.Y., where Bruce created in 1995 a magical canopy walkway for his students as chair of the School’s Science Department. I visited Bruce’s 80-feet high canopy, built into mature red oak trees with wooden walkways, surrounded by sugar maple, shagbark hickory, and American beech trees. So, why not go with Bruce and a few of his students to the Peruvian Amazon and do some zip-wiring atop those tall rainforest trees? And why not – as I was working in television – film the experience for PBS? Deed done, and that zip-wire ride was terrifying! Now a distinguished ecologist, Bruce as educator-explorer has led expeditions especially to the tropics, addressing science and conservation issues.

Max Nicholson

British ornithologist and conservationist extraordinaire Max Nicholson entered my life in 1990 in England. I bravely approached him to work with me on an Oxford Book of the Environment, a collection of environmental quotations gathered across history. And he was game! Author of “Songs of Wild Birds,” and “The Environmental Revolution” and more, he’d helped found and guide the World Wildlife Fund, the first international conservation organization, and quickly funded a fledgling Greenpeace’s efforts in preserving whales. We had many discussions on how such an Oxford Book of the Environment would be constructed, and Max had interested the Oxford University Press. But alas, the interested editor received a manuscript for an Oxford Book on Nature, thus our book would present too much overlapping!

Chandler Robbins

The late great birder and wildlife biologist Chan Robbins used to counsel birders, “Cup your hands behind your ears – it will amplify the sound by 50 percent.” With years of listening to dawn choruses and searching out where our neotropical and resident birds live and breed, he moved fast upon learning from Rachel Carson the effects of pesticides on birds to create the Breeding Bird Survey. I visited him at his office in Patuxent, MD, writing about his 50th anniversary celebration working for the US Fish & Wildlife’s Migratory Bird Population Station. Chan visited the Greenwich Audubon Center in 2013, in his wheelchair, cheerful as ever. He importantly addressed how the rising deer population was bad for birds. I featured Chan in 2016 in Living Bird Magazine marking the 60th anniversary of his banding Wisdom the Laysan Albatross. Wisdom had survived in that time flying the equivalent of six roundtrips to the moon.

Linda Macaulay

Greenwich’s Linda Macaulay has a Library named for her and her late husband Bill, the Macaulay Library of Sound at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. The Library now hosts 2,013,000 bird recordings – 982,000 from the U.S. and over a million from other countries, shares Dr. Ian Owens, the Lab’s executive director. Of those bird recordings he reports, “Linda Macaulay has contributed about 6,100 recordings from 53 countries, making up 2,834 species of birds—over a quarter of all birds in the world.” And I’ve had the pleasure of learning and writing about Linda’s extraordinary recording life across 30-plus years, like what it’s like to record in a rainforest: “It’s not risk free. My husband got malaria once; the leeches in Asia drove me nuts. I always get into jiggers…Your equipment has to work. People have to be quiet.” The great neotropical birder Ted Parker had encouraged her efforts in learning bird songs. “He’d say, “If you hear it 100 times, you’ll know them.” The Library’s recorded bird songs have been used by “generations of researchers,” says Dr. Owens, “to answer fundamental questions of bird behavior, evolution, and taxonomy.”

Katy Boynton Payne

Katy, who lives in Ithaca, N.Y., who I am privileged to know, traces her skills in the discoveries of the sounds of the world’s two largest mammals, whales and elephants to her knowledge of music – she majored in music at Cornell. But her love of nature was surely in her gene – her grandfather being the wildlife illustrator Louis Agassiz Fuertes. I remember vividly her stories of being in Patagonia with her biologist husband Roger studying right whales with their four children. The Paynes would then discover and research the songs of humpback whales. But the Paynes split and Katy’s research brought the serendipitous discovery of elephant communication in a zoo in Portland, Oregon. She’d come away hearing little communication between the elephants but recalled later having felt vibrations similar to those felt in her church when an organist played the lowest notes. Indeed, elephants communicate by low-frequency sound.

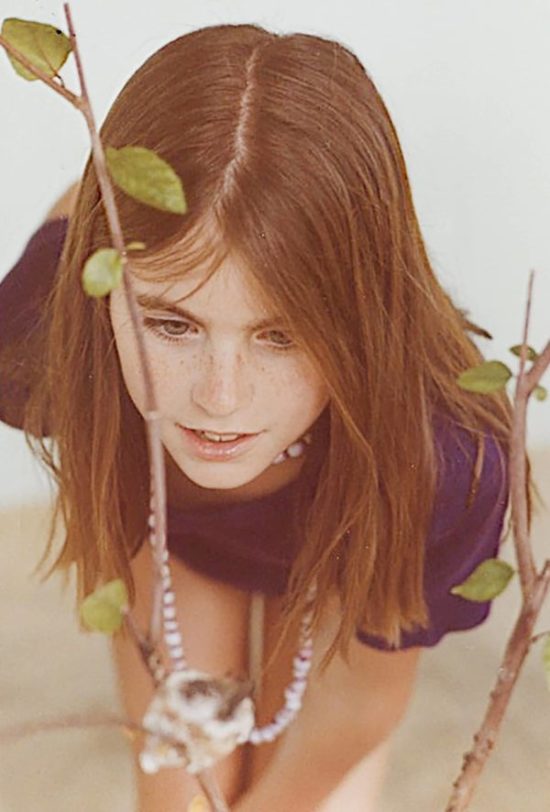

Melissa Groo

My daughter Melissa Groo, a Greenwich Academy graduate, obtained her master’s in education at Stanford University, then landed an impressive job with the Rockefeller Foundation in Cleveland, Ohio. The year was 1999 when she was drawn to a talk being presented by a zoologist/researcher in the Bioacoustics Research Program at the Laboratory of Ornithology at Cornell University on the subject of elephant communication. The speaker was Katy Payne.

So overwhelmed by Katy’s research, Melissa asked afterwards if she could be of help. She was taken on as an assistant and soon found herself in the Central African Republic studying the communications of forest elephants. From videographer to photographer Melissa would choose to be in her own words a “Wildlife and conservation photographer, writer-teacher-speaker-wildlife warrior. My work is my love for animals made visible.” Most definitely, and often prize winning as with her Audubon winning Great Egret photograph so magnificently displayed in the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. Melissa is my gift extraordinaire.