By Anne W. Semmes

The decades long and distinguished career of luminist painter Peter Arguimbau is being crowned by his successful lifelong pursuit to rediscover the antique formulas used by the Flemish painters in the Golden Age of Dutch Art, realized in the work of such Old Masters as Rembrandt and Rubins. He spells out his hard-won discovery, and the extraordinary learning curve of his own art experience in his new book, “Rembrandt’s Lost Secret.”

The book begins with a two-page elegantly crafted “Flow Chart” depicting “The Evolution of Oil Painting from 2,000 BC to 2,000 AD,” surely a testament of Arguimbau’s scholarship. It is followed by his “Self Portrait” at age 65, painted some seven years ago in luminist fashion years after making his discovery. That aha moment came at a happily pivotal moment in his life.

Soon to be married and settling in Greenwich in 1986 and setting up his studio in Stamford (later in back-country Greenwich), he tells of being invited to the Tall Ships Parade in New York City and with his sketchbook starts his career as a marine artist. “Marine painting satisfied two things,” he writes, “my desire to paint subjects that reflected on the country’s historical heritage, and my love for water and sky. I had always gravitated toward painting water scenes, the mix of reality and reflections making for pensive, dramatic light.”

He relied on his “hard-won knowledge of drying oil varnishes.” He aspired to “the quality of Renaissance art” even though he hadn’t found “the complete technique.” He had given up on his hunt for “the vaunted secret formula” those great artists had never publicly shared.

He just happened at that moment to be learning how to play guitar from an art colleague who presented him with a folio of antique Italian violin varnish recipes. “From the moment I applied the varnish to canvas,” Arguimbau writes, “I knew I was onto something. The medium had a startling immediacy, the colors bright and beautiful, the canvas vibrating with prismatic tones.”

“The more I painted,” he writes, “the more accomplished I felt. I no longer had to wait for the oil to dry; the varnish set readily, allowing me to layer suppositions over it, without the oil running…I was painting faster than I’d ever painted before, following my inspiration on the canvas, no need to wait for the paint to dry. Not only could I control how fast or slow the paint dried, but the gel medium also enabled me to pursue the finest detail or blend the layers. It was magical.”

What Arguimbau had discovered was, “the equal of the Maroger Medium, but without mastic, which would oxidize and blacken over time.” At age eight Arguimbau had become transfixed by the Maroger Medium introduced by his father, Vincent, also a painter who learned the technique from his teacher Frank Mason of the Art Students League. “The magic of the medium,” Arguimbau writes, “was its viscosity: it would remain firm and stable until stroked with a brush, when it would then liquify and solidify until moved again. You could form hard, stiff edges of ribbonlike brush strokes and then later melt them into smooth, thin washes with an internal amber glow.”

But how to prove he had found that lost medium. “I couldn’t say I had discovered Rubin’s technique or Van Eyck’s or Rembrandt’s technique because people wouldn’t believe it. I had no proof. So, it took me 20 years to get proof,” he tells. He had various means. Count his catboat he used not only for his painting but as a testing ground for his varnishes. His Catboat Association membership won him a rare 10-minute visit in Venice – where he had a studio – with a Maestro of a Murano glassblower laboratory where he saw similar painting materials passed down for generations. “Glass blowers were using the same technology as the luthiers and the painters.”

Of course, he writes, “I kept the discovery to myself…I had no interest in claiming equality with the Old Masters—I would not have claimed to be their equal in talent, merely in materials.” He would instead have his paintings speak for themselves. “My clients recognized the brilliant colors and effects in my paintings and started collecting my work—the interest in my work, and the career stability it provided, was enough for me. I figured I could retire to my backcountry suburban compound and be content with my 1850’s restored studio/gallery.”

Based on his experience, he writes, “the conclusive recipe for the ‘lost gel medium’ of the Old Masters is in Joseph Michelman’s ‘Violin Varnish,’ a book chronicling his attempt to recreate the varnishes used by Italian violin luthiers between 1550 and 1750.” He then follows with a recipe of listed materials to create “the gel medium.”

He follows with a show and tell of how to “recreate a portrait by Rembrandt.” “First, you would grind some white and put on one side of the palette. On the other half you would dish out some iron oxide varnish, and then with a wide brush, loaded with the dark varnish, cover your panel in a swirling motion…”

But for those wishing to follow along Arguimbau’s ambitious learning curve, there is that dropout of Vassar College intended to defer him from the draft at age 19, Vietnam War time, and later escape to Spain where he can claim royalty on his mother’s side, and diligent copying of great art across Europe. He would learn sidewalk painting in Italy but more importantly get invited to view Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel art up close and personal and learn to his dismay that the systematic cleaning was “damaging and irreversible” to that great art, leaving it exposed to acid pollution.

Arguimbau would take that knowledge home to New York City and copy Michelangelo’s “Creation” scenes for many months on the pavement by Fifth Avenue’s St. Thomas Episcopal Church in an effort to raise funds to help bring a stop to that cleaning of the art of the Sistine Chapel.

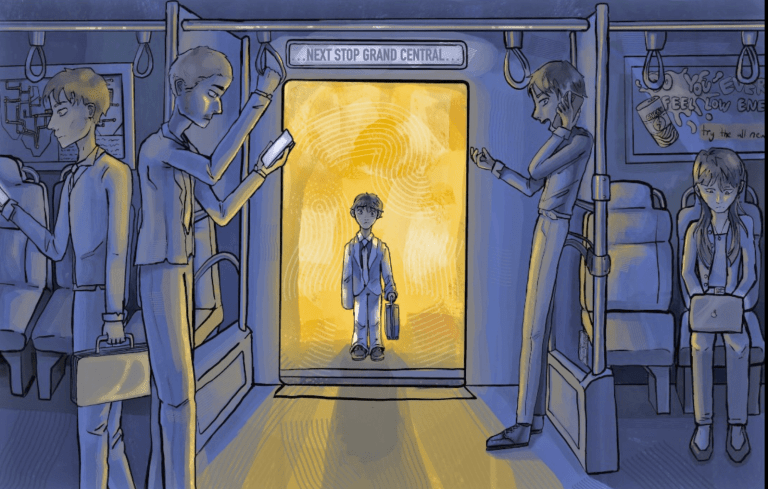

With his painting signature of Bronco Layne (Layne being his middle name), Arguimbau’s marine paintings and landscapes remain a mainstay, warranting his Mariner Gallery in Newport, RI presided over by his son Andre. He ends his book with his raison d’etre he writes, “that another generation of artists may see fit to experiment with my humble discovery and continue making art in a tradition that stretches back to the Golden Age of Art. Hope that artists today will examine the Old Masters with these new gel mediums – free again to paint like Rembrandt, where for the last three centuries it was denied.”