By Anne W. Semmes

Third generation Greenwich gentleman Jonathan “Jan” DuBois is a popular speaker at his town’s English-Speaking Union events. He’s erudite, Harvard educated, and in love with history. His topic for the November 16 ESU meeting of 65 attendees at the Round Hill Club was the Bloomsbury Group, known for “a circle of friends who were extremely intellectual and interested in the arts in the broadest sense of the word,” Jan’s words. And amongst them was a particular hero of Jan’s John Maynard Keynes, “a great economist.”

Not sure Jan would follow along here, but what came to mind as he spelled out the history of these artists and writers and game changers was another group local to Greenwich – the Cos Cob Art Colony – in a somewhat similar time period, the beginning of the 20th century. But back to Jan and his amazing sharing.

The Bloomsbury Group “were collectively responsible over a period of time for changing the taste of Great Britain, from Victorian styles and manners to modern styles, manners of art and writing.” There was Virginia [Stephen] Woolf and husband Leonard Woolf, and Virginia’s sister Vanessa Bell and husband Clive Bell, and Duncan Grant, and E.M. Foster, and Lytton Strachey, and Roger Fry.

And they would gather in a townhouse in the Bloomsbury district in London’s West End near the British Museum. “And they lived sometimes in the Charlston farmhouse, in Sussex that had extra rooms, and men and women would live there in quite free relations.” And the dress was not Victorian layers of clothing, “But in very simple, comfortable clothes to garden in and then come right to the dinner table in the way that they lived.”

Not quite the Holley Boarding House in Cos Cob, where artists J. Alden Weir, Theodore Robinson, John Henry Twachtman, Childe Hassam, Elmer Livington MacRae, and writers Lincoln Steffens and Willa Cather would gather and dine, and we don’t quite know the rest…

“But what’s interesting,” Jan continued, “These were upper middle class English families. They were not aristocrats, they were not confined by the social conventions of the aristocratic class, and they were independently wealthy…well-read, highly educated. They believed in educating their children and passed on their values…what we would now think of as liberal thinking of questioning whether women should have the right to vote. There were suffragettes within their family tree.”

So, it was Virginia’s brother Thoby Stephen, at college at Cambridge in 1899, who had “made friends at that time with a whole series of people who then became Bloomsbury…And all of these people who then joined later including John Maynard Keynes, Roger Fry (art critic and post-impressionist painter), E.M Foster (novelist) and Duncan Grant (post-Impressionist painter). By 1904, the Stephen family “had moved to Bloomsbury and lived on Russell Square.”

“They never called themselves the Bloomsbury Group,” noted Jan. “Virginia would refer in letters to individuals as being Bloomsbury, but they were together because they wanted to sit and talk. And the conversations would range of many subjects, of literature, of art, of exhibits, and end up in deep philosophical discussions about the nature of beauty and the nature of rational thought and can one reason one’s way to an understanding of aesthetics.”

“These dinners would go on until late in the evening with whiskey and smoke filling the rooms, and spilled over to weekends where they would get together. And the house they would gather in was that Charlston farmhouse bought by Vanessa Bell (open marriage with Clive) and Duncan Grant. And this was after she had romanced Roger Fry. “And Roger Fry was a very serious artist,” said Jan. “And they became painting partners, and he was mentoring Vanessa in her painting about the post-Impressionist world of more modern art. And he thought he would have a life partner in Vanessa, except she then became enormously enamored of Duncan Grant.”

“And there were these social jealousies that went on as the partners swung this way and that way between genders and between marriages,” shared Jan. “But Maynard Keynes became very enamored of Duncan Grant,” until 1921 when he became “entranced by a performance of the Sergei Diaghilev ballet group. And he went on 10 consecutive nights of the Sleeping Beauty performance till he got his courage up to invite the [British] diva whose name was Lydia Sokolava to have dinner with him. And the dinner led to their marriage that really was of wonderful support for Keynes in times of terrible unemployment and depression, and the recession that came in the 1930s. They had an absolutely wonderful marriage relationship.”

And then there was so much more of the evolving careers and accomplishments of that talented group. How in 1911, “Roger Fry had organized an exhibit with the help of Maynard Keynes to introduce to English taste the post-Impressionist work of Cezanne, Van Gogh and Manet. These were a shock to the English…Fry followed up the next year with an even more modern works exhibition of works of Matisse, Derain, and Picasso.”

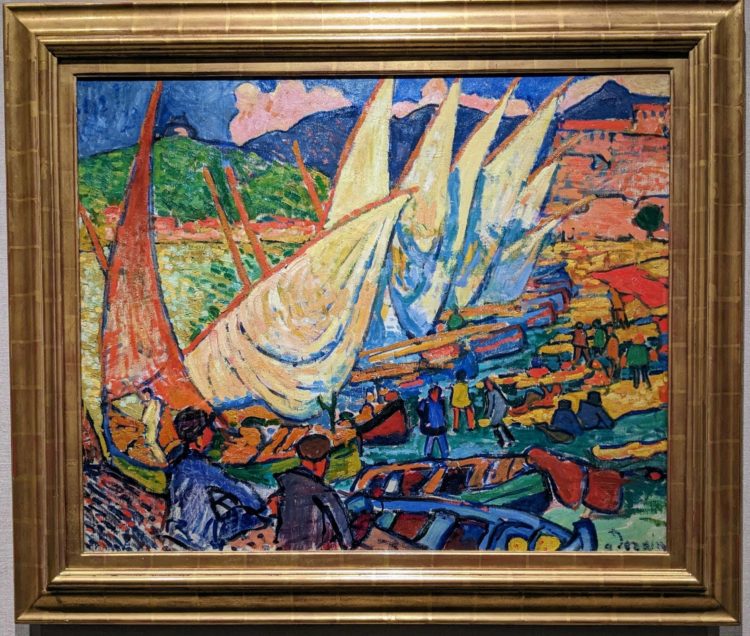

Jan then showed a photo of a painting by André Derain dated 1905 he had recently taken when he and wife Ann were visiting the Metropolitan Museum’s show, “Vertigo of Color: Matisse, Derain, and the Origins of Fauvism.” These artists, said Jan, “were interested in shape, in harmony of colors, in wild colors, having no particular relationship to the actual reality that they were showing. You see, the boats are not blue, and the clouds are not pink.”

At this moment Jan spotted his wife holding up a card, a gentle reminder he was over his talk time. (Yes, theirs too is “an absolutely wonderful marriage relationship.”)

But there was one other moment meaningful for this writer when Jan mentioned Virginia Woolf’s book “A Room of One’s Own,” as “a summary of two lectures she gave on what does it take for a woman to realize success in writing and in literature.” He shared that I’d brought the book to him at the talk as a formative influence, showing him on the back cover the quote, “There will be woman Shakespeare’s in the future, Mrs. Woolf urges, provided women can find the two keys to freedom: fixed incomes and rooms of their own.”

The last word must go to Jan’s hero John Maynard Keynes. At the end Jan shared a quote describing the influence of Keynes on history. It was from the Bretton Woods Conference held in New Hampshire in 1944 where Keynes had helped “forge the postwar international monetary order.” “Keynes” said British economist Lionel Robbins, “must be one of the most remarkable men that ever lived. The quick logic, the bird-like swoop of intuition, the vivid fancy, the wide vision, above all the comparable sense of the fitness of words, all combined to make something beyond the limit of ordinary human achievement. He uses the classical style of our life and language. It is true, but it is shot through with something which is not traditional. A unique unearthly quality of which one can only say that is pure genius.”

The Bloomsbury Group writ large! Thank you, Jan DuBois!