By Anne W. Semmes

Gaia is the third extraordinary astronomical space exploration project introduced by my astronomer stepbrother Michael Snowden, who lives in New Zealand. And Gaia is the acronym for Global Astrometric Interferometer for Astrophysics, a spacecraft/satellite four meters [13-feet] across, equipped with two telescopes on its European Space Agency astronomical observatory mission to create the largest, most precise three-dimensional map of the Milky Way.

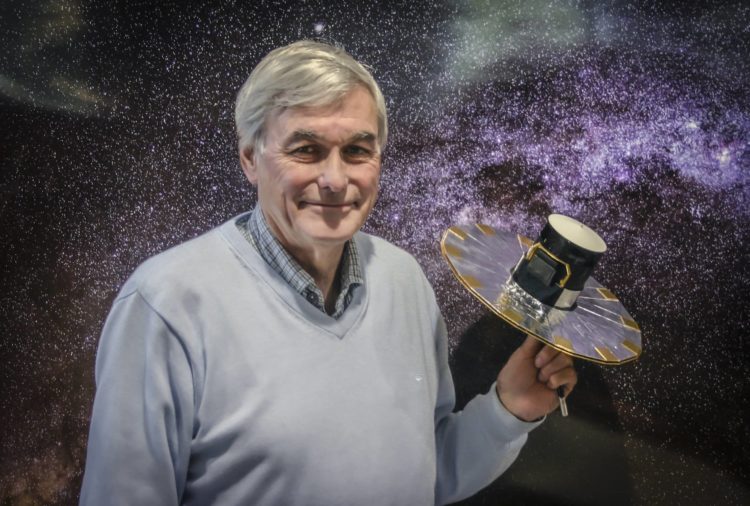

The man behind this mission is Gerry Gilmore, another New Zealander, long situated in Great Britian, but recently retired as Professor of Experimental Philosophy at Cambridge University’s Institute of Astronomy. We caught up with Gerry on Zoom in his Cambridge office where he’s also stepped back as UK Principal Investigator for the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium.

“Now, that’s a huge, complicated task,” Gerry addresses that data processing, “involving hundreds of people and huge computers all across Europe. But the data set is enormous…And will continue for another seven years until it’s all finished.” And what he sees as “most remarkable is just how precise the data really is. It has lived up to everybody’s expectations.

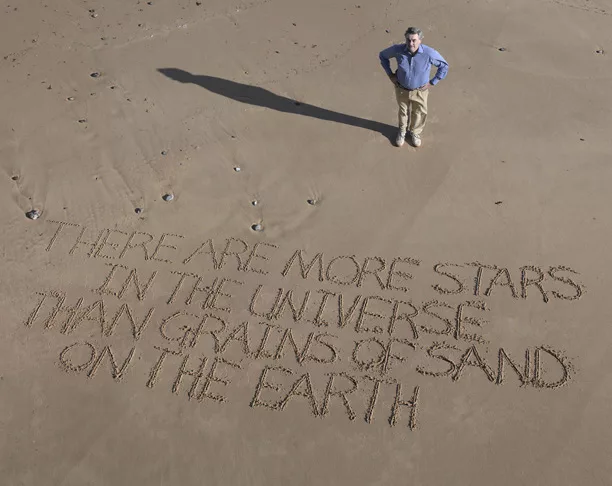

So, the ambition was to try and study a billion stars, and in fact, it’s about two and a half billion that have ended up being done, plus an awful lot of other stuff as well.”

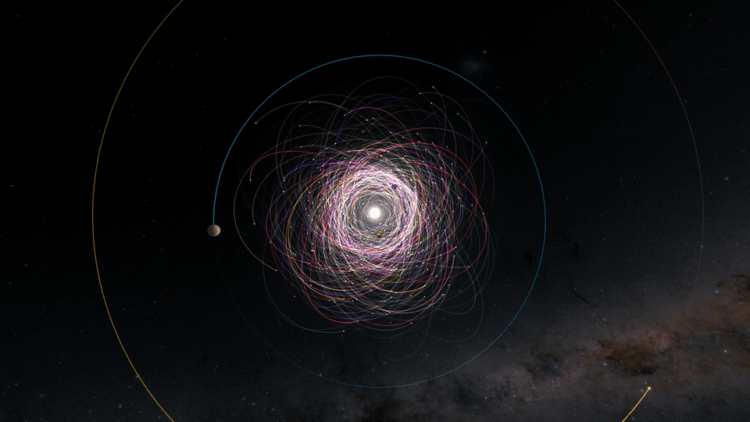

“What we didn’t expect was just how dynamic the Milky Way is,” he continues. “We can actually watch everything in the Milky Way move, including the Milky Way galaxy itself. So instead of seeing these rather pretty little pictures, that wallpaper sort of pictures that we see coming out of Hubble, with all the gorgeous galaxies out there, what we’re seeing is a real living, moving, oscillating, changing, twisting, pulsating thing. And that was vastly more information and vastly more interesting than we realized.

“So, we’d known since the 1990s that the Milky Way was continuing to merge with other galaxies and evolve and was being shaken up by that,” he noted, “because I’d discovered the big merger of another galaxy with the Milky Way that is ongoing.” The Milky Way had started “as some little pile of matter forming stars, and then another galaxy came in.” And now he adds, “We can actually see the first big thing that ever happened to the Milky Way. We can say, ‘That star came from there. This star came from there.’ That was totally unanticipated. So, we can just literally unpack the basic history of the Milky Way all the way back.”

Another Gaia discovery was getting up close and personal with “our two nearby big galaxies, the Large Magellanic Clouds (only visible in the Southern Hemisphere) and seeing “what a big influence they’re having on the Milky Way.” In those Clouds are “its own little cloud of satellite galaxies not known to exist. So, there’s this cluster of galaxies that’s coming in, and it’s so big that the Milky Way is being twisted and sloshing around because of the Large Magellanic Cloud…The two of them are doing a dynamic tango now. It is completely remarkable. None of that was known.”

Are these discoveries pointing to the age of the Milky Way? “That doesn’t come so much directly from Gaia,” he tells, “but the oldest stars and the oldest structures must be as old as anything in the Universe, which means that they will have formed at about 13 and a half billion years ago. The oldest things we can see nearby are the same age as these very faint distant things that the James Webb telescope is seeing. So, James Webb is showing us what it looked like when it was first formed, and we’re seeing what it is now. And in our own Milky Way, we’re able to deduce everything that happened in between.”

And isn’t Gaia mapping out some 150,000 asteroids? “So, there’s loads of telescopes searching around and discovering them. But they can’t very accurately tell you how they’re moving. So, Gaia is able to track these asteroids and find out how they’re moving. And from that, you can predict, ‘Are they dangerous or not?’ You can never do that unless you know how they’re moving. So, look for asteroids that are actually coming at us out of the sun. As far as we know, all of the famous historical mega killer asteroids have come at us out of the sun. They’re called Apollo asteroids for that obvious reason. And they’re almost impossible to find. Fortunately, there are not many of them. Otherwise, we’d all be dead. So that’s another sort of planetary safety thing that you get for free by mapping the sky with high precision.”

So, there’s been news of another spacecraft Euclid now inventorying space? “Euclid, technologically, is based on Gaia,” he says. “But its challenge is quite different. Instead of measuring how things are moving, it is just making an atlas. It’ll be ultra precise image quality, better image quality than Hubble. Euclid is measuring many billions of very distant galaxies. And the light from those galaxies as it comes through intervening galaxies on its way to us gets bent and distorted. So, Euclid is measuring all those twists to try and weigh all of the matter that’s between us and those background galaxies.”

Gerry’s discovery path as an astrophysicist has surely been an adventure. Raised on the South Island of New Zealand, he found he was “rather good at physics” and would get his doctorate in astronomy at the University of Canterbury. At Cambridge where he’s been for over three decades he’s been quoted as “weighing galaxies for a living.” During that time, he would witness “a complete technological revolution in ground-based astronomy. And that’s when digital data – cameras as we now use them, took over from photography,” he notes. And he was fortunate “to be one of the leaders at the front of that revolution and make some very substantial advances in our knowledge of the Milky Way.”

His definitive work on Gaia began in the early 1990s, working with the European Space Agency, “to build a big mission to really push the limits of what we could do in understanding the Milky Way.” It would evolve to be given provisional approval in 1995, and finally approved in 2000. “Then for the next 13 years, the design was worked out in more detail. It was an exceptional spacecraft, because it had to be vastly more rigid and precise and stable than anything that had been built before…The whole thing is basically a ring with two telescopes hanging on it. It was the first ever large structure made from a special ceramic, called silicon carbide. Silicon carbide is an ancient powder…Tutankhamun’s mask is partly painted with silicon carbide. If you melt this stuff, you end up with a material that’s weight for weight compared to steel. It’s about a hundred times stronger and about 10,000 times less sensitive to temperature. Gaia was the first thing ever built of it, so it took them a long time to learn how to do that.”

He recalls that memorable launch day, Christmas of 2013. “I was able to be there as well.

There’s a European Space Center at a place called Kourou in French Guiana. It’s on the sort of bulge of South America that is just below Florida. It was a big, beautiful launch. It was on a Russian Soyuz rocket, which were and still are, very reliable rockets.”

Four years later Gerry Gilmore would be awarded with two other colleagues the Sir Arthur C. Clarke Award “For the successful design and manufacture of the Gaia spacecraft and telescope which for the last three years has been accurately measuring the location and motion of the stars.” Arthur C. Clarke was a lifelong friend of my stepbrother Michael Snowden. For these astronomers this planet is truly a small world!

Up next is U.S. based LIGO – the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory. Its purpose, as its name suggests, is to detect gravitational waves.