By Anne W. Semmes

Recently Greenwich was graced by the visit of the Very Rev. Dr. Robert Willis the Dean Emeritus of Canterbury Cathedral, surely a cradle of Christianity. With his delightful partner of 20-plus years, Fletcher Banner, they spent a week at Christ Church, with Willis speaking often, and enjoying greatly hanging out upstairs in the Church’s Dogwood Book store. “People would come and some had no idea who we were and they’d ask where to find a particular book, which would start a great conversation.”

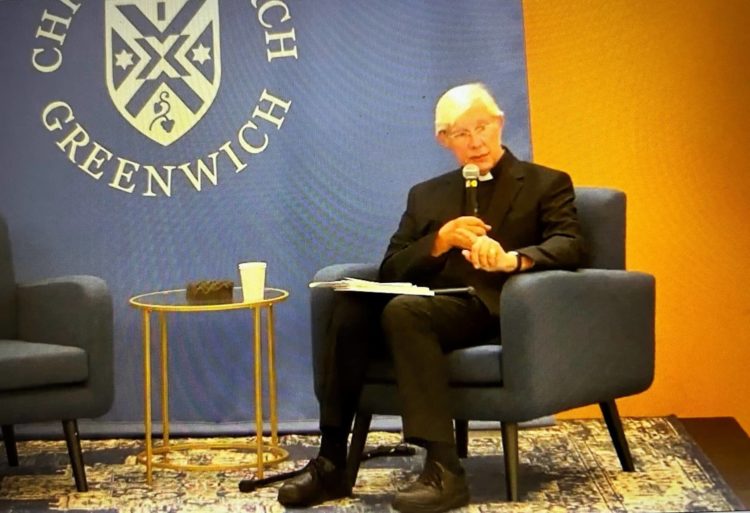

Dean Willis is great at sharing. Millions across the world tuned in to his morning worship in his Cathedral Garden, with mischievous cats during Covid when his Cathedral was closed down. But most memorable did I find his Christ Church Forum talk on saints and joy. Willis equates joy with creativity. “I firmly believe,” he began, “that when you are being creative in a way that is particular to your own gifts, you are never nearer to God the creator.”

He has found, “When people have discovered a particular gift, it might be in making a relationship or it might be in building something intricate…I’ve seen people build great sailing boats, and goodness knows what in their drawing room and they just get enormous pleasure from it.” And that pleasure “has caused them to have interests and talk to other folk in a completely different way.” Creativity he called, “one of the great gifts of God to each of us.”

And look to the saints, he told, “to help us through life at particular times.” For inspiration he said look at those stained-glass windows of saints, “at the way in which the light shines through…those pictures tell the story of the character of the particular saints.” For instance, in St. Paul’s letter to the Thessalonians, “reckoned to be the very first piece of the New Testament written down,” he had written to the Christians as the saints of Thessaloniki. Willis added, “If you think of sainthood as nothing to do with you, you are on the wrong path because the moment you are connected with a Christian community, you are called to be saints.”

And look to Saint Benedict, “the patron saint of Europe and the father of monasticism” and “his rule book for communities,” shared Willis, “which understood the frailty and temptations of human life in community…And he said every part of your personality and body, mind, and spirit, must be exercised each day.”

Another saint came into Willis’ life when his mother died. “It was in 1985 and I picked up a book at the bookstore at Tisbury, my parish church in the countryside, called ‘God’s Fool: The Life of Francis of Assisi,’ by Julien Green…It’s a beautiful biography of St. Francis set out in story form and you meet all the characters of Francis’s life…and during the reading of this book, I used to take it out into the woods, I had a Welsh Springer spaniel, Ben, who loved going walking in the woods…And it all fitted in with the song of the birds and the spring or the autumn leaves. And it began to be a great help.”

At the end of that sad year Willis was drawn to travel to Assisi, but not on a tour. “I just wanted to go just me.” He traveled at his birthday time in May…It couldn’t have been a better decision for me. It was a perfect week. I wasn’t with anyone at all but would talk to people as we’ve done in the bookshop this week.” And he kept a diary. “I’ve kept a journal all through my ministry and it’s a very useful thing to do. I advise anyone to keep a journal because two or three sentences when you look back will actually conjure up the whole day for you.”

He “completely fell in love with Assisi… I sat in Assisi and looked down on the river Topino…being able just to think thoughts about how my ministry might go forward at that time and also about how the Franciscan order had helped in this. But then, “someone came around the corner…a middle-aged lady who pronounced herself to be a Franciscan nun from France.” Might she sit with him? With some hesitation he welcomed her. After an hour’s conversation, “one felt she’d been sent almost like a ministering angel…She stood up and I said to her, should we keep in touch? She said, ‘I’ll give you my details, but that’s not the important thing. We’ll pray for each other – when push comes to shove, prayer is the only thing.’”

Willis also found help “from people who weren’t particularly saints, but their words would help when I read them,” such as the American/English poet, TS Eliot. “He wrote a play for Canterbury Cathedral, ‘Murder in the Cathedral’ about the assassination of Beckett by the Four Knights…But during the rehearsals, the producer cut out two lines.” Those two lines: “Time present and time past/Are both perhaps present in time future, /And time future contained in time past,” would begin Eliot’s book of poetry, “Four Quartets” that would win him the Nobel Prize in Literature. Willis called it Eliot’s “best spiritual work and I always carry it with me.”

The Four Quartets he said “are all about particular places. The first Quartet is called Burnt Norton which is a country house in the West Country… The next East Coker is a village near the parish of Sherburne where Eliot is buried.” And after that is The Dry Salvages – a rocky stretch near Rockport, MA where the Eliot family had a holiday home. And finally Little Gidding [in Cambridgeshire], “which was a religious community at the time when the English civil war was about to break out… Eliot saw this place as a place of great holiness.”

He then read to us toward the end of Little Gidding: “We shall not cease from exploration/And the end of all our exploring/ will be to arrive where we started/ And know the place for the first time.” “That’s an amazing thing,” said Willis. “You only learn the meaning of your beginnings by having gone right through to the end and finding yourself again and recognizing it for the first time. Eliot needs to be read over and over.”

At the end Willis returned to that light shining through stained glass. “We had an immense amount of glass in Canterbury. Some of it was from the 11th century. It had even survived the fire of 1174. And there were many saints in the windows. There were also ordinary people in the windows.” And then we were taken to that “little parish church” in Kent [All Saints Church] where he and Fletcher often take others in the village of Tudeley that the artist Chagall has made famous. To commemorate their daughter lost in a sailing accident Sir Henry and Lady D’Avigdor Goldsmid engaged Chagall to create the church’s east window.

Chagall, nearing the end of his life, came to see the unveiling. “He stood and looked at this beautiful east window,” told Willis, “And he said, ‘I must do every window in this church.’” But Sir Henry responded, “‘I don’t think we could afford that.” Chagall responded, said Willis, “There’s no charge. This will be a holy vocation for me. I want people to realize creation and the love of God as they see the glass and the sun changing all the time.” “He himself was of the Jewish faith,” said Willis, “and exiled from his own country in Russia. But he did one crucifixion after another, and Christ was always placed in the middle of painful and catastrophic scenes…at the same time extending his arms over a wonderful landscape where little creatures are there.”

Willis concluded. “And every time we take people there, they are able to point out things that they’re seeing, which we haven’t discovered yet, but we would. I think that that kind of artistic creativity is exceptional, but every one of us has with us a particular gift to share.”