By Jack Creeden

It’s hard to believe we are midway through the fall semester. What happened to those warm September days when we were in orientation mode? It’s time to get ready for Halloween parades and costume parties. Fall sports are coming to a close. Gym and rink rats are headed toward basketball courts and ice hockey arenas. The fall term is rushing past us.

In this column I often focus on issues affecting students. We have talked about challenges with technology, loss of skills because of Covid, the developmental stages of social-emotional growth in students, and anxiety about standardized tests scores. No one has any solution to the madness of the college admission process other than to play the game as everybody ese does, fearing that to abstain will jeopardize a student’s status in the admissions race.

Sometimes I wonder if the focus on students, while of value, causes us to minimize the role of parents in creating many of the problems confronting schools today? What’s really going on when parents demand curricular change, a different class placement for a child or accuse the teacher of doing a poor job? Why is the child’s poor performance on a class assignment or test attributed to the teacher’s skill level? In what rational model can one link a college admission denial to the failure of the school to adequately promote the student’s capabilities?

I worry about parents today. While we spend a considerable amount of time analyzing student mental health and well-being, perhaps we are mistaken when we do not wonder aloud about what motivates parents to behave so poorly?

One cannot dismiss the anxiety parents now feel about sending a son or daughter off to school or college, once a guaranteed safe location, a veritable ivory tower that is now described as a soft target for would-be perpetrators of gun violence. And in our world of 24/7 social media where everybody feels free to shout out their opinions as facts in as offensive a manner imaginable, is there any wonder that the same modes of behavior get transferred to in-person confrontations between teachers and parents, who feel their child or they themselves have been aggrieved by something the school or teacher has said or done?

Schools are awash with curricular wars with each side trading vitriolic barbs about the damaging impact of one another’s views. What is each side really worried about? That one’s child might come to a conclusion about a specific historical event, school of thought or societal structure that differs from what mom or dad believes, or have espoused for most of their adult life? Isn’t it part of normal adolescent development to rebel against the values of parents in order to develop a healthy and independent perspective of one’s own? Isn’t it a tradition for dinner table conversations with one’s teenagers to dissolve into angry denunciations of what mom and dad stand for and do not understand about today’s youth?

Parental anxiety over financial stability is sometimes offered as a way to explain the uber control parents seek to have over their child’s education. Some argue that future financial health for our children can no longer be guaranteed and, therefore, parents must act now to secure quality control over the curriculum or after-school activity. How else can parents increase the child’s chances of admission to “the best” college in an irrational and totally unpredictable college admission process? Isn’t it a parent’s responsibility to do everything in their control to fill in any deficiencies or shortcomings for their children? And yet some of the worst examples of offensive and belligerent parental behaviors occur in public and independent schools with significant resources and blue-ribbon curricula located in affluent neighborhoods. Where’s the deficit?

Maybe that’s it, the overwhelming belief that as a parent, I have to act to secure my children’s success and happiness. When they are unhappy or sad, I too share that emotion and look for ways that as an adult, I can fix it for my child. That way we both will be happy.

When my child is disconsolate because of a class placement, course grade, unpleasant interaction on the playground or getting cut from the team, rather than help the child deal with the reality of that event, the adult takes corrective action. It leads to conversations where parents say first to the coach or teacher, “Understand this is non-negotiable. He/she needs this to be changed.” It’s the social media equivalent of posting your opinion in CAPS! There will be no need for any discussion.

I once worked with a therapist who helped me understand the emotional highs and lows of early adolescents and teenagers. Their moods shifts and angry denunciations about school, classes, teachers or coaches were part of normal adolescent development. When teens or pre-teens are happy, they exude joyfulness. When they are sad or angry, there are no filters. Everybody else is responsible for their emotional reaction.

The therapist reminded me that this period of development was like riding a roller coaster. The highs are exhilarating, and the crashing lows are steep at least temporarily. The therapist urged parents to stay on the platform of the ride, and not get in the car with their teenagers. That way the parent can help the child moderate his or her emotions and deal with decisions or experiences without the excesses of the emotional response.

Perhaps we cannot easily understand the complex reasons behind some of the problematic parental behaviors we are witnessing. But by staying on the platform and not getting on the roller coaster with pre-teens and teens, we might better serve the long-term growth and healthy development of our children.

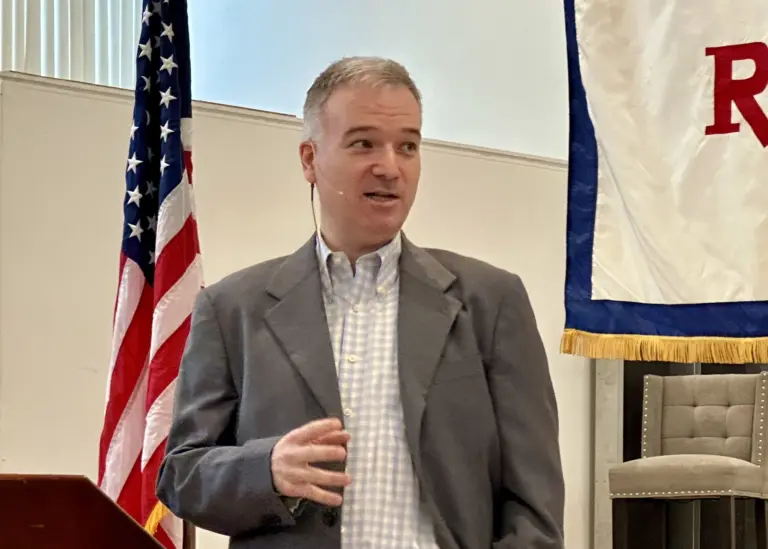

Jack Creeden is the Head of Whitby School. He has been head of several independent schools, and Chair of the National Association of Independent Schools Board of Trustees. He writes and presents on governance, cross-cultural competence and the impact of teaching on student learning.