By Anne W. Semmes

Alex Brash of Riverside has led a life with a love of nature, especially birds and trees, and spent his professional life working to save that nature. And now, with the publication of his new book, “Whaler at Twilight, – A True Account of Whaling and Redemption in the South Pacific,” a first telling of his great, great grandfather’s 10 extraordinary years of whaling in the South Pacific, Brash has in the doing made the past relevant to the present.

“I always thought it was heavily weird,” he shares, “that I would end up being the great-great-grandson of a whaler and logger who went out and cleared some of New Zealand’s last great forests, and obviously chased some of the greatest, coolest beasts in the sea.”

It’s a harrowing tale that begins in the 1840’s with young Robert “Rob” Armstrong of Baltimore beset with alcoholism and full of guilt and shame, signing onto a whaling voyage out of New Bedford, giving up his first job in dentistry – with his parents passed, having lived with a respected Methodist shopkeeper uncle.

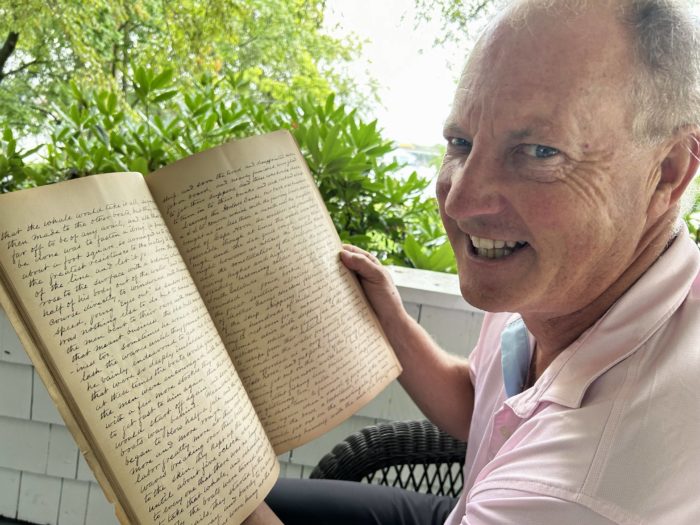

Fast forward to now retired Alex Brash finally letting his mother pull out of her closet that black leather trunk with manuscript of his ancestor, passed down through generations, knowing for decades it would be of interest to her son. Mind you, he’d been busy in his career of forestry, heading up Connecticut Audubon, having lobbied for our national parks, and kicked off the Forever Wild Project of now 47 park preserves in New York City. (Add his being a first responder on 9/11.)

“It’s totally amazing,” says Brash, “that he [Rob] actually came back from that experience, and what a gift – as he went through life, he then took the time to go back and think about it all and draft a full narrative of what his experience was.”

Yes, it took Rob nearly 10 whaling and logging years, and on his homeward voyage in 1859 to finally lift up his heart to his God with his prayer, “May I be ever watchful lest my conduct I shall bring reproach upon the cross of Christ through my falling away from him.”

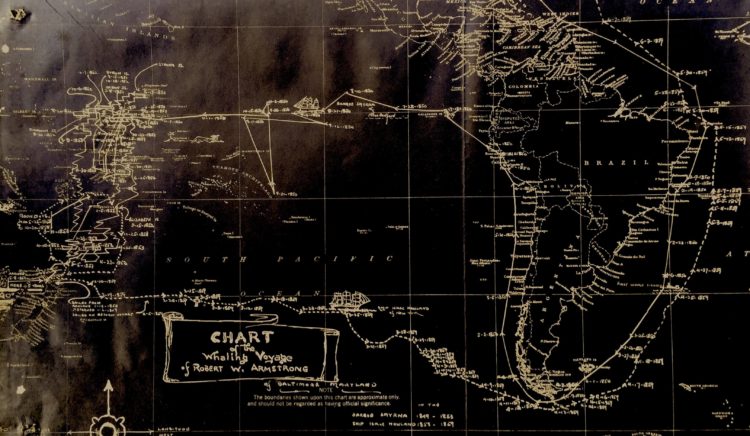

Three months of reading and transcribing Rob’s manuscript led Brash to the New Bedford Whaling Museum where to his astonishment he learned from the librarian, “We know of Robert Armstrong quite well – In fact we have his logbooks.” Brash, with his good research, had the makings of a book, wherein he would add bits and pieces of Rob’s log to his manuscript. But he determined there was much fleshing out needed of that whaling history and more.

“I probably worked on it two to three years,” Brash tells, “doing all the background research and fact-checking and building up the context.” And credit today’s online research powers: “You uncover these books that have long passed copyright, and someone’s digitized them,” such as that “incredible” coincidence of finding an autobiography written by the nephew who had served on his uncle-captain’s ship that Rob had learned was involved in a mutiny from a “cock and bull” story told him by islanders aboard his ship.

But Brash wanted to go the extra mile – why not follow the footsteps of his ancestor, especially that whaling trajectory starting from New Bedford down the west coast of South America, around Cape Horn? And what about New Zealand where all that vicious logging of ancient trees was done by his ancestor?

Brash sailed those seas knowing both from his research and from Rob’s autobiography what life was like aboard those whaling ships. “The whole concept and thought of whaling is an incredibly painful one to contemplate,” tells Brash, “when I’ve been a conservationist my entire life. It’s painful just to think at the first level of harvesting, as they did, and even more to the point, harvesting a highly intelligent mammal with culture, and just the physical pain obviously it brought. And on top of that, what it did to the entire social structure of various whale species. It broke up families, it broke up entire breeding systems, it broke up breeding grounds, it created havoc among them. And, as we know, many of the species have never really returned.”

Brash lays out the whole harvesting process in his riveting chapter on “The Crimson Sea.” But notes how Rob in his log and autobiography never addresses that pain of whale killing.

“He clearly and explicitly avoids delving into the tragedy among the whales that he and his compatriots caused.” Returning and taken in by his Baltimore community, and then writing his autobiography in his 60’s, “He decides to leave some of the more or less savory aspects of his time on the side.”

In New Zealand Brash, with his degree in forest science, traveled to the different sites on the North Island where Rob was harvesting the ancient Kauri trees, and then “the other species of kahikatea there.” Brash would arrive to see tree plantations. “You’ve missed the worst part, which is clearing the old growth, which is truly gut-wrenching. But even on a plantation that’s been in place for 40 or 50 years, obviously you’re displacing all the wildlife. There’s not very little left in New Zealand that’s either not pastureland or established plantation forests.”

Brash begins his last chapter, reflectively called “The Infinite Abyss” with “Perhaps after all this reflection, on family history and the fate of our planet, I am in too deep.” But he continues, “We need to assess the planet’s carrying capacity, and our interactions with our biological partners on this our one and only home, Earth.” He then appropriately quotes from Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick” [published at the beginning of Rob’s odyssey]. “Melville had wondered, even 170 years ago, ‘whether Leviathan can long endure so wide a chase, and so remorseless a havoc; whether he must not at last be exterminated from the waters, and the last whale, like the last man, smoke his last pipe, and then himself evaporate in the final puff.’”

So, is this what Brash is pointing to in his book title of “Whaler At Twilight?” He responds, “A Whaler at Twilight – is it the twilight of whaling? Is it the twilight of that whaler, or is it a whaler contemplating the twilight of his morality? I didn’t have an answer, that’s why it was sort of a cool title.”