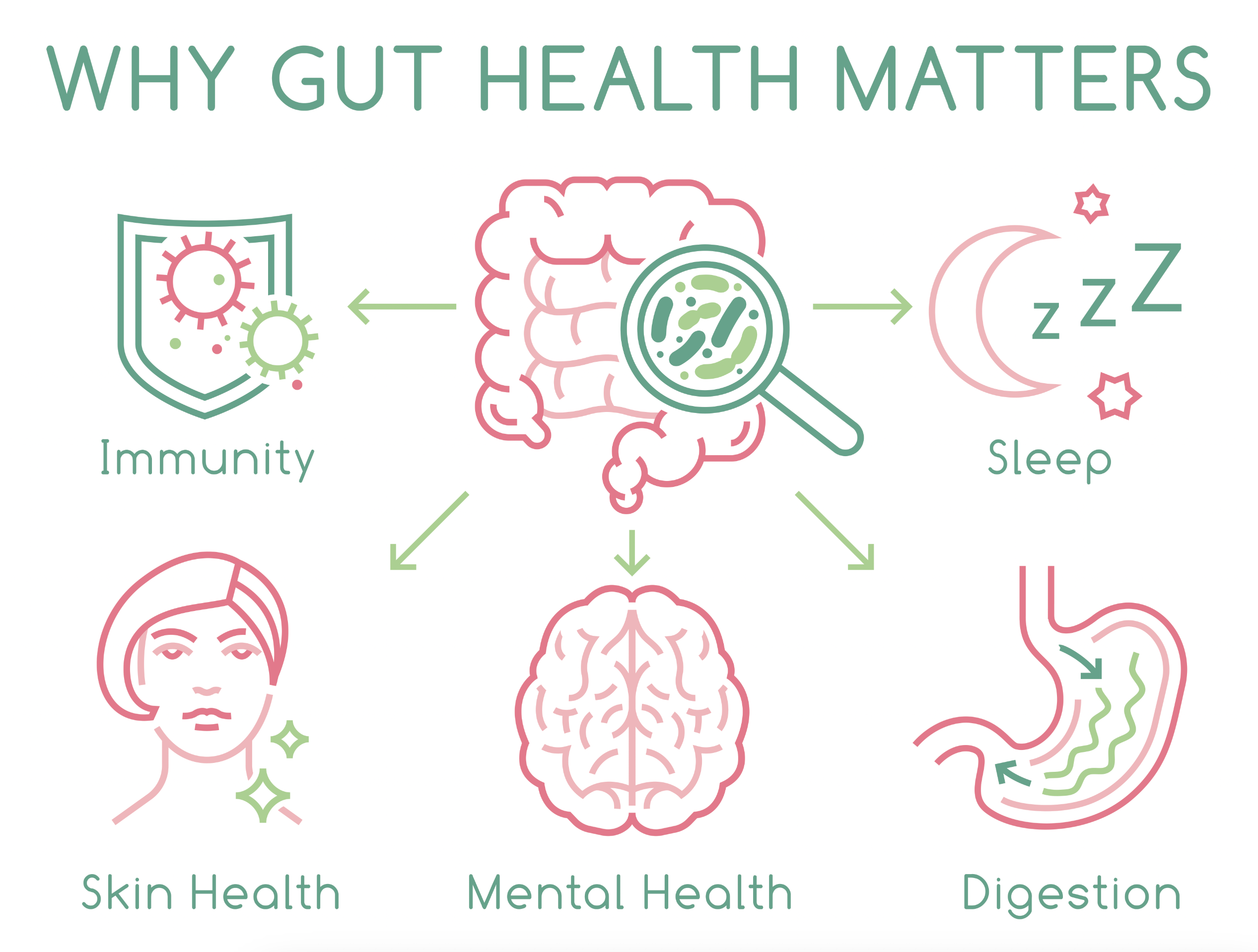

New research has shown that the microbiome – the vast communities of microbes in our digestive tract – can affect our emotions and cognition. Studies have suggested that the microbiome plays a role in influencing moods and the state of psychiatric disorders, as well as information processing. However, the mechanisms behind how the microbiome interacts with the brain have remained elusive.

Recent research has built on earlier studies that demonstrate the microbiome’s involvement in responses to stress. Focusing on fear and how it fades over time, researchers have identified differences in cell wiring, brain activity, and gene expression in mice with depleted microbiomes. The study also identified four metabolic compounds with neurological effects that were far less common in the blood serum, cerebrospinal fluid, and stool of the mice with impaired microbiomes.

The researchers were intrigued by the concept that microbes inhabiting our bodies could affect our feelings and actions. The study’s lead author and a postdoctoral associate at Weill Cornell Medicine, Coco Chu, set out to examine these interactions in detail with the help of psychiatrists, microbiologists, immunologists, and scientists from other fields.

The research has pinpointed a brief window after birth when restoring the microbiome could still prevent adult behavioral deficits. The microbiome appeared to be critical in the first few weeks after birth, which fits into the larger idea that circuits governing fear sensitivity are impressionable during early life.

The research on microbial effects on the nervous system is a young field, and there is even uncertainty around what the effects are. Previous experiments reached inconsistent or contradictory conclusions about whether microbiome changes helped animals to unlearn fear responses.

The findings from the recent study have given extra weight to the specific mechanism causing the behavior observed, pointing to the possibility of predicting who is most vulnerable to disorders like post-traumatic stress disorder.

Although the interactions of the brain and the gut microbiome differ in humans and mice, the study has identified potential interventions targeting the microbiome that might be most effective in infancy and childhood when the microbiome is still developing, and early programming takes place in the brain.

The study’s findings could have significant implications for the future of potential therapies and deepen scientific knowledge around the mechanisms that influence core human behaviors