The healthcare facility that we know as The Nathaniel Witherell began as a Municipal Hospital in 1920, a refuge for those suffering from tuberculosis. At the turn of the twentieth century, Greenwich patients with communicable diseases like tuberculosis, diphtheria, and scarlet fever were hard-pressed to find a hospital that could care for them and often were placed far from home. The land for a Municipal Hospital was bequeathed to the town by Robert Bruce in 1903. The building itself was proposed and financed by Rebecca Witherell, and eventually renamed for her husband, Nathaniel, in 1946.

Between the Municipal Hospital and the complex we now know as The Nathaniel Witherell, many iterations have taken place. As the need for care for tuberculosis patients declined, one-half of the building was set aside for those who were chronically ill. Over the years, the complex has undergone renovations and enlargements to better serve the needs of the community through its skilled nursing, short-term rehabilitation, and memory care units. The Oral History Project (OHP) in its many interviews, has preserved the recollections of two residents who were dedicated to bettering the conditions of those housed at Nathaniel Witherell.

Nancy “Nan” Rockefeller was co-founder and first president of the auxiliary of The Nathaniel Witherell. She was interviewed in 1978 by OHP volunteer, Esther Smith. “I had become interested in 1928 and, as much as I could, I would go up by myself and see what I could do to help the patients.” In 1939, she worked for the Red Cross “because the war was coming.” During the war, she became a Gray Lady. The Gray Ladies were a volunteer organization started under the American Red Cross in 1918, which provided friendly, personal, non-medical services to patients. For three years, Nan “worked as a Red Cross worker in the army camp, as a motor corps driver, Gray Lady, and a nurse’s aide all in one.”

After the war, Nan continued her volunteerism at The Nathaniel Witherell. In 1956, she was approached by Gertrude duPont Howland, “a Gray Lady who worked there” about starting an auxiliary. So, as Nan described it, “We started an auxiliary which is going full blast now and has turned the Nathaniel Witherell Home . . . into really, I think, one of the best nursing homes in the country. And it was through the auxiliary that they have really humanized the place.”

One of the accomplishments of the Auxiliary, of which Nan was particularly proud, was to get church services started at Nathaniel Witherell because “when you come to the end of the road, you certainly need faith and hope and comfort.” Nan was instrumental in raising additional money for a chapel at the time Nathaniel Witherell was being renovated and expanded. The cornerstone for the Nathaniel Witherell Chapel was laid in 1976.

At that time of her interview in 1978, Nan stated, “…we have a waiting list of over a hundred people desperate to get in, and the list becomes longer as people live longer and Greenwich grows.” Nan Rockefeller’s spirit, drive, and concern for others was evident: “I really love helping people because I really love them…It’s been a great pleasure and satisfaction.”

Gertrude duPont Howland was interviewed by OHP volunteer Margaret French in 1987. She was an inveterate volunteer in the town of Greenwich who also contributed much to Nathaniel Witherell. As part of the Gray Ladies at Nathaniel Witherell in the 1940s, she wanted to improve the everyday lot of the patients there. It started by bringing “each patient a gift and a little happy birthday cake on a pretty tray.”

At the time, Gertrude Howland was not impressed by the conditions and services for the patients. Because of the war, there was a shortage of doctors and nurses and “there was absolutely no program of any description whatsoever at Nathaniel Witherell . . . no physical therapy, no occupational therapy, no religious services of any description.” At that time, the facility was under the Department of Health and they “had so many other things to supervise – restaurants, sewage, property, you name it – that they really didn’t get out to Nathaniel Witherell very often.” To make it worse, according to Mrs. Howland, the floors were “battleship brown linoleum,” the walls were tan “because all municipally owned buildings were painted the same color,” and the beds were white. “That was it until the Gray Ladies got there.”

At the time, Gertrude Howland was not impressed by the conditions and services for the patients. Because of the war, there was a shortage of doctors and nurses and “there was absolutely no program of any description whatsoever at Nathaniel Witherell . . . no physical therapy, no occupational therapy, no religious services of any description.” At that time, the facility was under the Department of Health and they “had so many other things to supervise – restaurants, sewage, property, you name it – that they really didn’t get out to Nathaniel Witherell very often.” To make it worse, according to Mrs. Howland, the floors were “battleship brown linoleum,” the walls were tan “because all municipally owned buildings were painted the same color,” and the beds were white. “That was it until the Gray Ladies got there.”

Gertrude Howland had many ideas to expand the volunteer services at Nathaniel Witherell and, in concert with Nan Rockefeller, supported the formation of an Auxiliary in 1956. A number of services were initiated for the residents, funded by the Auxiliary, and “then the town fathers would see that it really was worth doing and the town would take over the cost of that.” This formula led to the funding and establishment of recreational, occupational, and physical therapists. “Then the place was growing in reputation.”

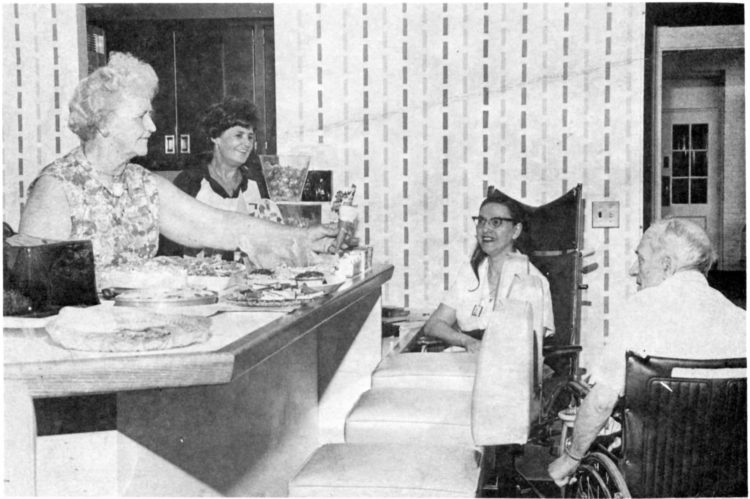

Howland discovered that “not a single patient was ever allowed to put their foot outdoors” because “so many of them are confused and might wander away.” Therefore, along with other volunteers, she begged Green Fingers Garden Club, of which she was an early member, “to put up a fenced-in garden that they could go out into without supervision…A perfectly beautiful garden is there now.” Also, with the new west wing, “we opened up a real beauty shop and a gift shop and a coffee shop and snack bar. I ran the gift shop for four years.”

Mrs. Howland is proud of the changes that she has seen in Nathaniel Witherell, from its days as a home for tubercular patients to its latest iteration at the time of her 1987 interview. “I have never been anywhere that was more civic minded than the people here in Greenwich are.”

The interviews entitled “Meeting the Needs of a Community” and “Missions Accomplished” may be read in their entirety at Greenwich Library and are available for purchase at the Oral History Project office. The OHP is sponsored by Friends of Greenwich Library. Visit the website at glohistory.org. Mary Jacobson serves as blog editor.