By Anne W. Semmes

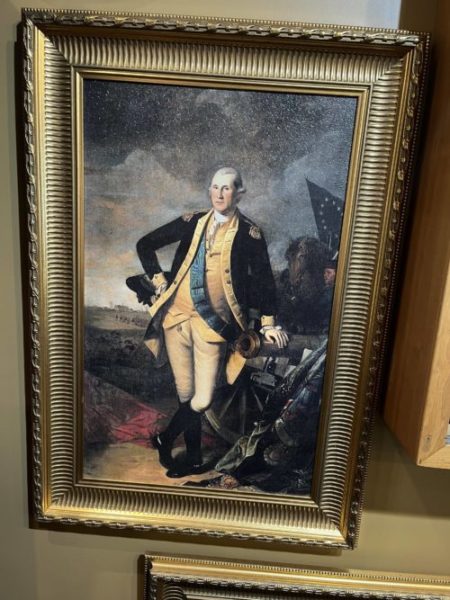

It was those impressive paintings of George Washington hung about, of all places, the august interior of Bennett Jewelers on Sound Beach Avenue in Old Greenwich that caught this reporter’s eye and curiosity. Having years ago been entranced by some of the formative influences of America’s Founding Father and first President it was intriguing to see such a painterly celebration of him in our local jewelers.

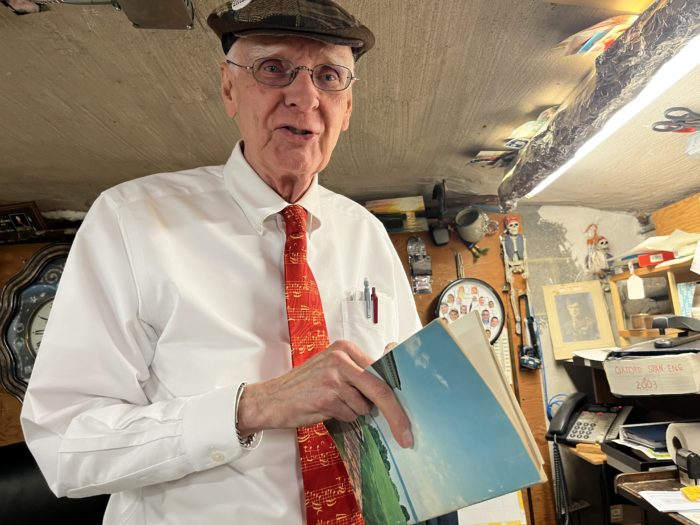

“You know he passed through Greenwich a number of times over the Mianus River Bridge,” shares Wyatt Bennett, third generation owner of said jewelry store, fellow Washington enthusiast and yes, historian, who has collected those reproductions of famous paintings of Washington. Bennett would trigger my quest to find those Washington footprints in Greenwich that would stretch across three decades. But first, what had fed Bennett’s interest in Washington?

Beneath the jewelry store is Bennett’s kingdom of history books and ticking clocks – he is a master clock repairer. So, it was the Revolutionary Period of our country that first claimed Bennett’s interest.

“I’ve always been interested in the 18th century,” he tells. “One of my favorite writers is Samuel Johnson and he sort of overlapped with the Revolutionary Period. He didn’t like Americans very much. ‘They should be grateful for everything we give them except killing them,’ he wrote.” Add to that Bennett’s dad had shared, “I’m not so sure I would’ve been a rebel then. I might’ve been a Tory.” Bennett explains, “You know a third of the people were rebellious, a third were Tories, wanting things to remain the same, and about a third were neutral and that was Washington’s third, which was to have complete independence…What caught my eye was Washington, he was really the key man.”

“Because of his character,” he continues. “He wasn’t a great general. Of the seven battles he would be involved in, maybe two he won. The other five were either lost or tied. He was very good at running away…They were tactical retreats…He took big risks that people didn’t think he really should have taken. He had many horses shot out from under him, but he got away with it. He knew he had to keep the army together. There was a rebellion by the officers. Right up here in Newburgh. They weren’t getting paid for what they had done, and they really wanted to take over the government. He wouldn’t let them do it. And they left with tears in their eyes after he asked them, ‘Don’t do this.’”

“And he saw the thing through, and not only the Revolution, but after the revolution when he became President. He really didn’t want to do that. He wanted to go back to Mount Vernon and raise his mules and have his booze, but they wouldn’t let him because he was so well liked…And there were no political parties really by then. Everybody loved him. And he knew that if he didn’t head things up, be the first president, our chances of staying together as a union were limited.”

So, Washington’s first footprint in Greenwich was in the winter of 1756 on his 24th birthday, February 22-26, when he was passing through town as a Colonel serving the British as commander of the Virginia Regiment in the French Indian War. So, he crosses over the Mianus River-Palmer Hill Road bridge that carried all Boston Post Road traffic back then, as he was headed for Boston to meet up with British Governor William Shirley of the Massachusetts Colony. But on his return, having met with “extreme difficulties” on the road south he returns via Long Island Sound.

The second time, it’s the summer of 1775, June 27, and Washington is 43 and now a General on his way to take command of the Continental Army in Cambridge, MA.

So, Bennett adds, “Greenwich was very rural at that time. There were a couple of houses on the Post Road. So if you blinked, you’d miss the Town. So, I guess he didn’t stay here. Maybe he went to Stamford, or Fairfield.”

The next spring of 1776, General Washington, now 44, passes through Greenwich on April 12 returning from Boston on his way to “build defenses in New York.” He has lunch at Knapp’s Tavern on the Post Road (now Putnam Cottage). (We have these footprint dates thanks to The Greenwich Historical Society’s history book, “Greenwich Before 2000.”)

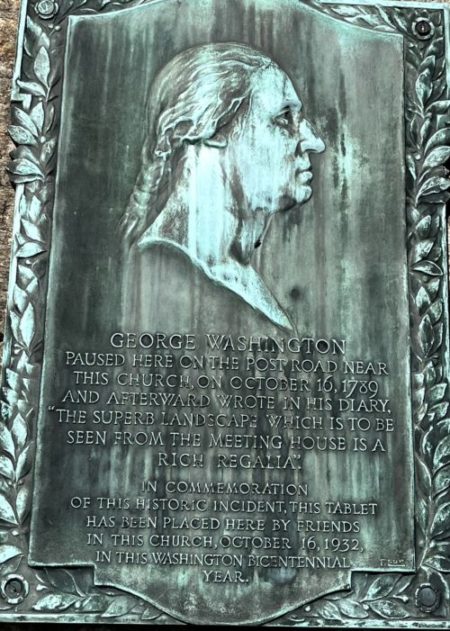

But come the fall of 1789, we have President Washington, age 57, telling us of his October 16 Greenwich visit in his own words in his diary. He stops by the West Society Meeting House, to become Second Congregational Church. “The superb Landscape,” he writes, “which is to be seen from the meeting house is a rich regalia. We found all the Farmers busily employed in gathering, grinding, and expressing the juice of their apples…” (Washington would document in his diary conversations he had with farmers on his travels.)

Part of Washington’s quote is seen on a plaque on the exterior of Second Congregational Church that includes a fine profile of the President modeled after the famous portrait by French sculptor Houdon, who eyed Washington for weeks at Mount Vernon to best capture his likeness.

President Washington’s mode of travel in those rough road days is described as riding in an open carriage drawn by four bay horses, followed by his white horse “Prescott” he would mount upon entering a town. “I think he wanted to go out and meet people and have them meet him,” says Bennett, “and they treated him like a God, in a sense, like a king. And he was a little wary about that…And that’s part of the reason why he chose not to stay in 1797 when they wanted him to run for a third term.

“He wanted to get back to Mount Vernon…George III said anybody who does that, he’ll be the greatest man in the world. You don’t give up that kind of power. He did.”

The two standout paintings Bennett has on display include the fine copy of Washington as Commander in Chief of the Continental Army at the Battle of Princeton, 1781, by Charles Willson Peale. And then the copy of that most famous painting of “Washington Crossing the Delaware” on Christmas night in 1776, by German artist Emanuel Leutze.

Bennett tells of taking his grandson to see that Leutze painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “It’s 20 by 40 feet,” he says, “and fills the whole room, but the original one was in a small museum in Germany that was bombed by the Allies in World War II.”

The story goes that Leutze had spent his formative years in Philadelphia in the 1830’s and 1840’s and been inspired by America’s patriotic passions and wanted to inspire similarly his fellow Germans during a time of rebellions spreading across Europe. Luckily, he also had a second version of the painting that he brought to the U.S. where it received tremendous praise as “the grandest, most majestic, and most effective painting ever exhibited in America.”

Finally, there was a sharing of books with Bennett from which this reporter had learned it was from a 17th century book by Sir Matthew Hale called “Contemplations, Moral and Divine” that Washington’s mother had drawn “many of those great maxims which she instilled into the mind of her son, and which had a powerful influence in molding his moral character.”

Bennett then offered a gift of a recent book he described as “a woman’s history of George Washington,” entitled “You Never Forget Your First,” by Alexis Coe. It is packed with information, including a chapter on “Washington’s Favorite Breakfast.” Yes, every day he had hoecakes (recipe included) “swimming in butter and honey” with three cups of tea.