On my watch – A visit with the fearless Helen Dillon before her moving day

By Anne W. Semmes

This week an extraordinary woman who’s led an extraordinary life is leaving Greenwich, Helen Dillon. Turning 93 in January, she is moving into assisted living in Massachusetts. But then Helen – I claim as friend – only retired a couple of years ago from her 20-years of volunteer work mentoring men behind bars in the maximum-security Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, New York.

Helen is a classy, forthright lady who I had the pleasure of writing about 12 years ago when she brought to Christ Church Greenwich a performance of “The Castle’ which stars four men who’ve spent an accumulated 70 years in prison. They tell about their lives before, during, and after they’ve left prison and found a home in The Castle, a group home in New York City, operated by the Fortune Society, named for Shakespeare’s line, “When in disgrace with fortune and men’s lives.”

Helen also has a documentary film called “25 to Life” aimed at teenagers, “at risk” kids produced by Amy Mooney of Greenwich. Helen had shared she felt “that most kids in the world today are at risk,” with “a lot of sentences seeming to be 25 to life.” That film she’s shown at the Boy’s and Girls Club, for Kids in Crisis, and various police stations in Fairfield County. And she had shown it at Sing Sing.

At last Sunday’s church service Helen was surprised when the Minister, Rev. Marek Zabriskie shared with the congregation her departure from Greenwich – she was glad her accompanying grandson was there for support. But she has brought many surprises of her prison ministry to her church. “I used to have what we call ‘Redemption Sunday’ at Christ Church,” she tells. “I would bring mostly returning citizens, ex-cons from the prison and they would preach the sermon and then be at the 10:10 [Forum] afterwards. I had trouble getting them out of the church, people were so interested in the men.”

She recalls another time she brought to church two women from the medium security Federal Correction Institute. “And it was funny, we walked into the Parish Hall and all the church ladies were against the wall. And when we left, they were hugging them and kissing them and saying, ‘Oh, can you come again?’”

It was at a Christ Church Forum that Helen had met up with a woman volunteering for PVS (Prisoner Visitation and Support) in Danbury’s Federal Correction Institution. “I was curious, and I thought this really sounds cool…And I did that for quite a while…You’d see seven, eight women a day and they would just come out and talk.” And then she learned about the AVP (Alternatives to Violence) program at Sing Sing.

To qualify there are three workshops to attend over three weekends. So, at Sing Sing, she was meeting with “mainly men the rest of those years, until they closed the prison down with Covid.” It was after that, with traveling in a van becoming more difficult that brought Helen’s retirement.

“Sing Sing has more programs than any prison in New York,” she tells. “So many of the men in Sing Sing are artists -they have become artists since they were in prison.” Asking one if he had ever painted before,” he answered, “No. You’re kidding. I was too busy gang banging.” For the first time in their life,” she tells, “They’re away from the streets and the chaos. And they have time. And you can’t believe the art they’re putting out.”

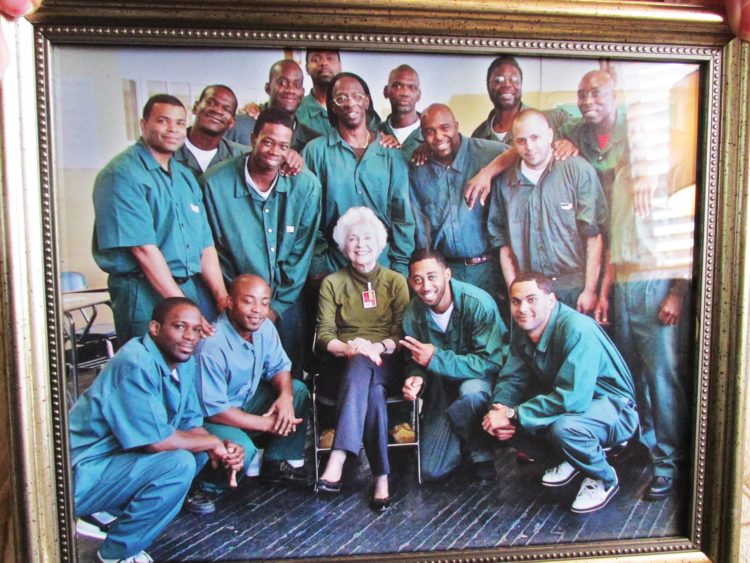

Helen pauses to ask her daughters who are helping her to pack to unpack that photo of her sitting in the middle of a large group of Sing Sing convicts. “I produced a film (as part of the prison’s Rehabilitation Through the Arts program),” she tells, “that features the men making a play and these were the men that were in the cast. And it’s fabulous. They came out and spoke from the heart. And these are all violent criminals. Look at how cute they are – a little different looking than Christ Church parishioners. They loved doing it. It is so good and so powerful.”

“That’s what my Redemption Sundays were about,” she notes. “What I learned was that even though somebody does a bad thing, they’re not a bad person.” To demonstrate she describes an AVP activity of the men in a circle, where the lead facilitator asks a question, “and then everyone answers it. And they got to me, and I couldn’t think of one.” Two people later she had an answer, “When ‘Jigsaw Jay’ (everyone has an affirmation name) said, ‘Wait a minute, wait a minute, Happy Helen’s thought of one, let her tell it before she forgets it.’ I thought that was so adorable,” says Helen. “That shows something about the soul of that person.”

“I work with the people who are trying to make a change,” notes Helen. “And they can’t get their trailers, unless they take AVP.” She explains: “They’re allowed to spend time in a trailer on the grounds with their families, obviously with guards around.”

In 15 of those years in Sing Sing Helen had a Greenwich AVP friend, Margaret Lechner, partner of now retired Audubon educator Ted Gilman. “Helen was really enthusiastic about amplifying the voices of the insiders, helping their stories get shared,” tells Margaret.

“And one of the things that she did above and beyond AVP,” Margaret shares, “was her Wednesday night support group. It was incredibly meaningful for the men to have that opportunity on a regular basis to meet and to have conversations… If something was bothering them, they found the mutual reinforcement to find a nonviolent solution to problem solve. She really held that space for them.”

And yet neither Lechner nor I knew of those years of Helen’s life before her prison ministry began. But it may show just how prepared she was to deal with “tough guys.” It’s there in a New York Times article dated 1981 with the headline, “The Hard-Work Ethic of Helen Dillon.” Helen was then part owner and vice president of the New York Jets making history as the only female executive of a NFL football team. She was reportedly a “raging football fan.”

In 1968 Helen inherited 25 percent ownership of the Jets from her father Donald Lillis. He would not see, like his only child and daughter Helen, the Jets win Sugar Bowl III the next year in 1969, called “the greatest upset in sports history,” starring quarterback Joe Namath.

For 16 years Helen, first with three children under the age of five, would attend everyday practices, then “board the team plane, laugh easily, tell jokes and ask how the new baby is at home.” She’d mother the players when they got hurt, and once at Shea Stadium “punched a woman, who, with her husband, had cursed the team.”

From 1976 to 1981, she reportedly never missed a road game. She enjoyed talking with the players and the coaches and was “treated kindly” by the men in her world. In 1984 she would sell her 25 percent share for five million dollars.

The proof is in the pudding – Helen Dillon was primed big time for her prison ministry.