The lasting legacy of Rudyard Kipling’s Great Spy Game as told in his novel “Kim”

By Anne W. Semmes

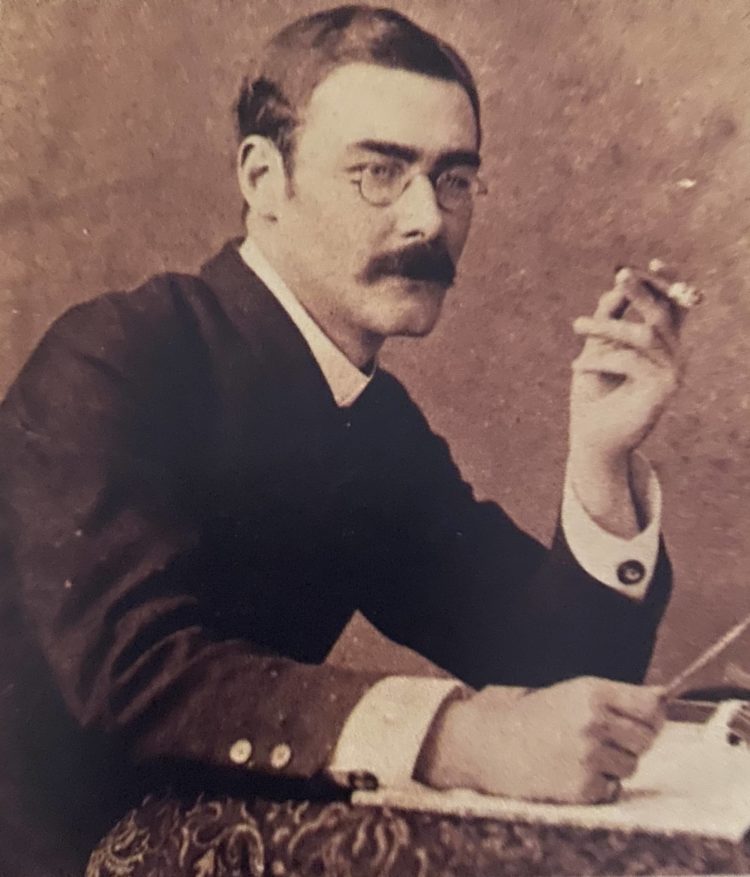

The late, great Rudyard Kipling, English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist, who was born in British India which inspired much of his work, was surely familiar to the 80 attendees of the recent meeting of the Greenwich Branch of the English-Speaking Union (ESU). Kipling’s “Just So” stories for children, and his “Jungle Books” are classics. But it was the historic impact of his novel “Kim” that was unveiled before the ESU members and guests gathered at the Round Hill Club luncheon on September 21.

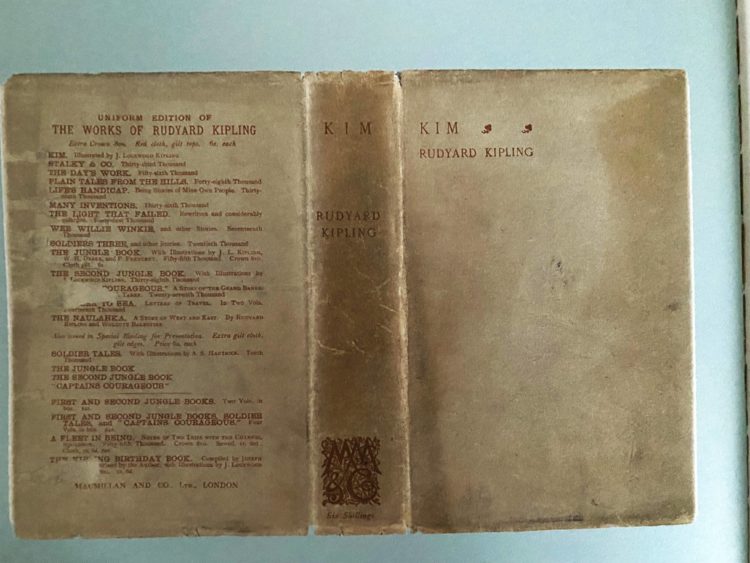

“It was Rudyard Kipling who introduced to the reading public the romance of the international spy, a character who became a hero of 20th century popular literature and film,” began guest lecturer and now five-year Old Greenwich resident, David Richards. Richards was introduced as having the world’s largest collection of Kipling’s first editions and manuscripts, now at Yale’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library. “And David is currently president of the London-based Kipling Society,” said Natalie Pray, ESU Greenwich Branch president.

For international spies think real life Cambridge spy Kim Philby, CIA Director Allen Dulles, CIA officer Kermit Roosevelt, or Ian Fleming’s fictional James Bond. Add John Buchan, spy thriller novelist, who “developed one Kim-like hero, Sandy Arbuthnot, an accomplished linguist and master of disguise,” told Richards. After Buchan’s ‘39 Steps’ (1915), came his best-selling thriller, “Greenmantle” (1916). Add John le Carré. “a veteran of both MI5 and MI6…who was fascinated with ‘Kim.’”

So, what was so intriguing about Kipling’s Kim? “The narrative,” told Richards, “recounts the wanderings of an Anglo-Irish Indian orphan, Kimball O’Hara, or Kim, on his sudden choice to accompany a lama on a religious quest, which leads through Kim’s friendship with the native horse trader, Mahbub Ali, to working for the British spymaster, Colonel Creighton, to the pursuit and final expulsion of two foreign agents, a Russian and a Frenchman, disguised as hunters, trying to stir up trouble on the Northwest Frontier region.”

“’Kim’ is a tale of international intrigue,” said Richards, “in the playing of the Great Game, a term Kipling’s book made current, between Great Britain and Russia for the control of the Indian subcontinent…Playing one’s role in the great game is Kipling’s metaphor for living the heroic life. And the British secret service in India serves as a trope to suggest a brotherhood of those dedicated to the heroic life. Through Kipling’s imagination, the real-life British secret service in India has been transformed into a sort of secret brotherhood whose mission is to protect the people from the chaos and evil that threaten without.”

And where did Kipling begin to spin out this heroic tale? The same house he was spinning out the “Just So” stories and “The Jungle Book,” near Brattleboro, Vermont! The house he built called Naulakha is a National Historic Landmark available to stay in with Kipling’s original furniture including the desk he wrote on.

“Kim” has been noted as “the foundational legend of the British Secret Service,” shared Richards. “And in October 1909, the [British] government created a foreign section of a new secret service bureau, that soon became… the ancestor of MI5, and a foreign department in charge of espionage, the forerunner of the secret intelligence service, SIS, or MI6, the home to the fictional spies James Bond and George Smiley, and to the real agents and later spy novelists, Somerset Maugham, Ian Fleming, Graham Greene, and John le Carré.

“And the fictional boy Kim was mightily admired by living men who became real spies… even to the point of assuming Kim’s name.” Such as Theodore Roosevelt’s grandson, Kermit Kim Roosevelt Jr., who served under Allen Dulles. “He was a Harvard-educated Arabist and a Kipling devotee.” And Kim Philby had been so nicknamed at age two by his father then serving in the Indian Civil Service.

Allen Dulles had early in his career taught English in an Indian mission school in Allahabad, India where Kipling had worked as a journalist. “Dulles first read Kim in 1914,” told Richards, “While sailing toward India to take up his teaching post, and he kept it with him his whole life. His well-worn copy was on his bedside table when he died. “

In later years when British military historian, John Keegan, had visited the Central Intelligence Agency headquarters at Langley, said Richards, “what impressed him most was its resemblance to British India’s political and secret service in the days of the Raj.” Keegan had noted in his book, “Warpaths,” “The CIA does indeed carry on the traditions of the Indian political service, the ethos of Kim and the Great Game. Mediation between the old power of the Anglo-Saxon world and the new is the CIA’s calling. It has assumed the mantle once worn by Kim’s masters as if it were a seamless garland.”

In 1901, Rudyard Kipling had written in “Kim,” told Richards, that, “When everyone is dead, the Great Game is finished, not before.” In 1967, Ian Fleming wrote in ‘The Spy Who Loved Me,’ ‘It’s nothing but a complicated game, but then so is international politics, diplomacy, all of the trappings of nationalism and the power complex that goes on between countries. Nobody will stop playing the game. That’s the appeal of spy novels today to the readers and despots.’”

Richards then had a sobering conclusion, sharing first a reflection of military historian, John Keegan, “written two years after 9/11, about the urgent need of modern espionage services to combat foreign terrorist cells. ‘The challenge will cast the agencies back in the methods which have come to appear outdated, even primitive, in the age of satellite surveillance and computer encryption.’

“Kipling’s Kim, who has survived in the modern times only as the delightful literary creation of a master novelist, may come to provide a model of the anti-fundamentalist agent with his ability to shed his European identity and to pass convincingly as a Muslim message carrier, Hindu gallant and a Buddhist holy man hanger-on, far superior to any holder of a PhD in higher mathematics.”