By Mary Jacobson

Oystering in Greenwich has a long and storied history that is indelibly intertwined with that of the Chard family of Greenwich. In 1976, Suzanne Kowalski of the Oral History Project interviewed Clarence Chard to learn about his family and its contributions to the history of oystering in our town.

Clarence Chard’s grandfather, Samuel Chard, began oystering off the Greenwich coastline in the 1870s. According to Clarence, “He had a shanty, they called it, on Brush Island (west of Mead’s Point), where he lived through the week. Then the boys would come down weekends with the horse and wagon and take him back up home to Cognewaugh (Road).”

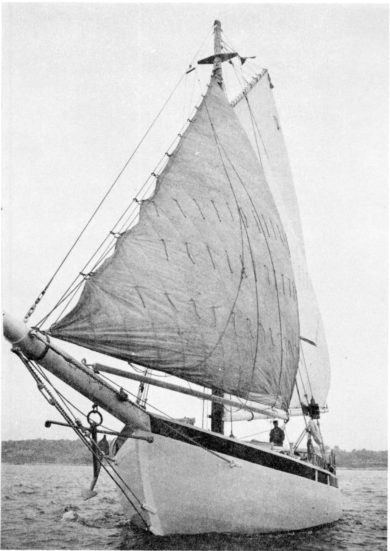

By the turn of the century shellfishing had become a lucrative business for local fishermen. Clarence’s father, William, born in 1868 in Cos Cob, oystered there until he retired in the late 1920s. Clarence, aged 18 in 1918, joined his father and his Uncle Stanley in the oystering business after graduation from Greenwich High School. “At that time the market boats came up from New York and we loaded them…In the early days, before my time, the oyster sloops (or scows, as they were called) used to go down…most people would call them barges, but we called them scows. They had the house on them; and they opened or shucked oysters right there.”

New England was especially known for the richness of its oyster industry. Chard explained that oysters secrete their spawn from June to September. “When the temperature of the water gets right, they secrete that spawn in the water and it swims around for a dozen or so days. Then it settles to the bottom and attaches itself to the shells and pebbles…the oysters settle on the shells there and grow…It’s because they had good natural settling ground. Connecticut seed (young transplantable oysters) used to be shipped all the way down to Chincoteague, Virginia in schooners. Some of the vessels would carry five thousand bushels of seed.”

Clarence vividly recalled growing up on Indian Harbor Drive watching the oyster sloops. Of the thirty-odd there, he began to name a number of them. “Well, there was the Ann Gertrude, the Florence T., the F.E. Webster, the Fannie S., the Piano, the Emma Jane, the Sarah Lucinda, and, of course, the Susie C. and the Samuel Chard—that was my father’s sloop (built in 1900).”

Clarence and his brother Bill bought the Susie C. from his Uncle Stanley in 1932 and would sail it to Bridgeport to oyster there. “There were over three hundred boats up there, years ago. When the fleet landed up in Bridgeport, why, there were some hot old times…the tricks they used to play on each other. Put things down their smoke pipes so the smoke would come out in the cabin, and things like that.”

The Chard family oyster beds were off Field Point, outside of Captain’s Island, and outside Greenwich Point “in the neighborhood of four hundred acres.” Chard recalled that “the best price we ever got (for oysters) was four dollars a bushel…I did sell a few, in later years, for sixteen dollars a bushel.” In his father’s time, when times were lean, “They raked clams out of a rowboat, and he had clam market enough to pay his men…There were a good many years we never made anything.”

In the 1920s oystering in New York State was condemned and Connecticut was restricted. As a result, “the whole west end of the Sound was a breeding place for stars (starfish),” the nemesis of oysters. “They’ll move in like a blanket sometimes, the stars will. Just cover the bottom…There were a couple of years that there were so many stars that, when we had a nice bed of oysters coming, we took them up and sold them before they were really of marketable size. We ran them over to Oyster Bay and sold them.”

The last boat the family built, utilizing both sail and power, was the Hope, built on Brush Island and launched in 1948. “But we didn’t have any oysters, so then we started dredging clams by power.” Nevertheless, Clarence remained hopeful for the future of oystering: “We know that things come in cycles with both fish and shellfish…I think that perhaps the oysters are liable to spawn again someday and live; and if they do, why there’ll be a rebirth of oystering.”

Today, oystering in Greenwich Harbor has had a rebirth. The Greenwich Shellfish Commission, begun in 1986, is considered an example for the State. Its mission to is “manage, protect, propagate and conserve the shellfish beds for both recreational and commercial use.” Local waters are tested sixteen times a year in thirty-six locations. Roger Bowgen, chairman of the GSC, states that there are now thirty million oysters in Greenwich waters.

Clarence Chard would be pleased.

The interview entitled “Oystering” may be read in its entirety at Greenwich Library and is available for purchase at the Oral History Project office. The OHP is sponsored by Friends of Greenwich Library. Visit the website at glohistory.org. Mary A. Jacobson, blog editor.