Why are our high school seniors stressed out? A Two-Part Series

By Gregg Pauletti

Part 1 – High school seniors have always stressed about college. What’s different?

Historically, the college application process has been a stressful aspect of a high school seniors world that is reserved for a short few weeks – first around the time of the traditional deadlines, and then again around the time when decisions are released. Students typically experience this period of time with a collective camaraderie, leaning on one another to work through their feelings, comforting one another through disappointment, and celebrating together upon the learning of good news.

The college admissions landscape has changed over the years – none more than the last two – but students are experiencing this longtime rite of passage differently. Why? Why are they unable to cope as well as they might have 5, 7 or 10 years ago? There are many possible explanations for this, but simply, it comes down to one word: pressure (read also: stress), from all angles. Don’t get me wrong, students who are following the path toward college have always felt pressure. For the most part, pressure has been a healthy aspect of the experience; it’s the driving force behind a student’s motivation academically as well as in formulating the plans needed to develop into a healthy, productive adult. Pressure is a vital part of everyone’s life and is experienced in many different ways – internally and externally. It is felt by each person uniquely, but usually within a range of tolerance. For our high school students, this tolerance is being eroded, and few students are able to withstand it as they used to.

The scapegoat is clear: COVID. To be fair, the pandemic has dramatically worsened the mental health crisis for high schoolers – but the crisis was slowly building years before 2020. So why are students in recent years unable to cope as well as before? What is different? Let’s examine what we know.

In 2009, more than 1 in 4 high school students experienced symptoms strong enough to be classified as depression, of which nearly 35% were female. Anxiety was occurring at a rate slightly higher for the same populations. By 2019, this number had increased by more than 40%, with girls being impacted the greatest, nearly half (46%) having experienced persistent feelings of hopelessness and sadness. While COVID may have dramatically increased the prevalence of mental health conditions in youth, it is clear from the data that this is a trend that began long before remote learning, lockdowns, and mandatory masks.

So what has driven the change during the last 12 years that might cause this smoldering mental health crisis? Let’s examine the statistics above for a moment. A few things occurred during these 10 years – the first is the use of the Common App, and subsequent ability for a student to easily apply to many schools seamlessly. The second is related to demographics – for decades, the number of women vs. men on college campuses has been greater, roughly 60/40 as of 2020, but the number of young women overtook young men in 2011 in terms of the number who have a college degree – a number that has since only grown, and makes sense from a mental health perspective, as illustrated in the paragraph before. Is something different about college the admission process itself, or the “social application environment” that is creating this unhealthy pressure, rather than an appropriate dose of “motivation-provoking” anxiety? If young women are the majority group applying to college and are also disproportionately being impacted adversely in terms of mental health, should we be examining the link between the two? Social forces on the application process have never really been studied, but the impact is clear. The college application environment in which students are experiencing and participating in has undergone substantial change, and although the admissions process is by and large the same, schools have modified their acceptance behavior as a result of economic, not academic and/or social forces.The tool for this behavior modification? Deadlines.

Part 2 – Deadlines

Part 1 of the series about high school students being stressed out explored the background of mental health and other pressures that high school students are experiencing. Ultimately, the conclusion is that the college application environment in which students are involved in is, at least in part, largely responsible for much of this change. In Part 2, we are going to take a dive into admissions deadlines and their impact on schools, their students, as well as the economic and social ramifications.

Deadlines, more specifically, Early Decision (ED) deadlines, were developed by colleges and universities in order to solidify their acceptance class – a way for them to better predict the number of students who will attend, after all of the acceptances were decided. The reason for this is that Early Decision is binding – students who apply to a school ED must attend – barring extraordinary circumstances, such as financial hardship. The schools also have a number of different options available to ensure that the student follows through with this decision, such as pressing the student’s college guidance office or “blacklisting”, a cruel process by which the school announces to other colleges that the student broke their contract, often resulting in the student’s other acceptances being rescinded. In the past, the most selective schools would use ED as a tool to build as much as 30% of the incoming class; an effective way to confidently add the best possible students to an incoming class. Early Decision applications are usually due in early November, months before Regular Decision applications, with acceptances, deferrals, and denials notifying students of their fate in and around December. ED is a great option for students who know exactly where they want to go (only about 20% of high school seniors actually do) – to attend the “perfect” school for a student in all aspects, academically, geographically, and financially. If there is any doubt about a school – for any reason – ED is generally taken off the table for that student.

From the lens of a college or university, building an incoming class is really difficult. There are a number of variables that schools must weigh in order to accurately determine the number of acceptances which will achieve their desired matriculated class. During the last 5 – 10 years, the use of ED to increase the guaranteed matriculated class has grown every year and is now used to admit as much as 60% of an incoming class for many colleges and universities. Thus, schools are turning to ED as their solution, which is logical from the academic and business perspective. From a student (and guidance counselor’s) perspective, this alone is a very good reason for students to apply ED – statistically speaking, students are more likely to gain admission to a school if they apply ED. If there is a way to increase your chance of getting into a school, of course that student should be encouraged to do it, right? Over the years, students (and the adults guiding them) have been led to believe that they will be more likely to get into a college that they just like (as opposed to love), and, because the ED statistics are in fact “true”, they are encouraged to apply in this manner.

Unfortunately this isn’t the whole picture. First, the reality is that in general, not all students are more likely to get admitted via ED. Second, students are applying to more schools than ever, peppering schools with applications via the Common App, often applying to 15 or more colleges. Consequently, colleges and universities are, in fact, admitting more students and have a higher acceptance rate via this process. Consequently they are falsely giving the appearance that it might be easier to be accepted. One can connect the dots, and clearly see that for students who are “borderline” (we are talking about students who have a 3.75 GPA rather than a 4.0), this process may not be the wisest decision. Essentially, we would be locking them into one particular school, all for a marginal increase in the likelihood that they’ll be admitted. Is this really what students want? What are the factors driving these decisions? There are two answers here – from a high school guidance counselor’s perspective – yes – applying ED is the solution. The reward for a high school having a student admitted to and consequently attend a top tier college matters. A LOT. There are very real financial and perceptual implications – high schools (especially private schools) invest heavily into their college guidance programs and need to show results. If the student is statistically more likely to be admitted, then they deem that to be worthy. From a student perspective, the answer is yes also, but only if that is the school that the student wants to attend with zero hesitation or doubt.

This little game that colleges and universities have created has inadvertently created a bit of a crisis for high school students.

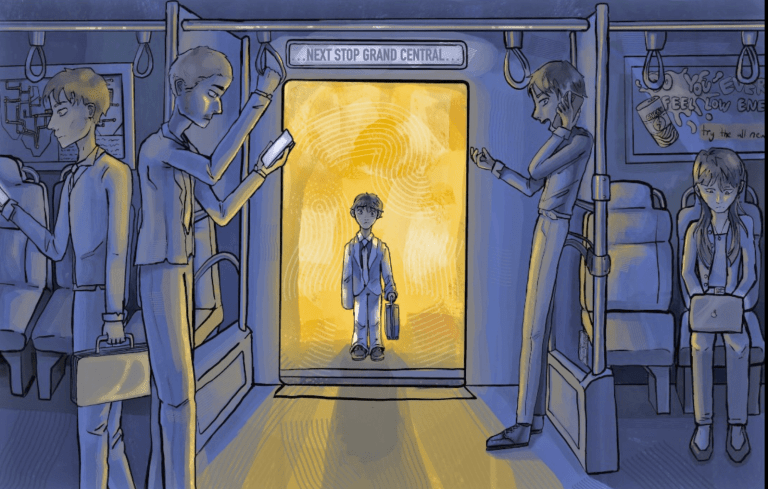

Colleges and universities, as well as their high school guidance counterparts, have slowly created a system in which social pressure has become the proverbial straw that broke the high schooler’s back. By pushing more students to attend college and encouraging students to apply early primarily for statistical reasons alone, we have created a situation where high school students who have not applied early, or been denied early believe that they somehow “failed” the process. Think about this, high achieving students believe that they actually are not worthy of going to a school all because of a process that was created to maximize the economic – not academic benefits of the college admissions process. Socially, these students are now comparing themselves to their counterparts who did receive admission early, and now must exercise a muscle that is seldom used in our hyperspeed technology age – delayed gratification – and wait until March. We have turned a little bit of pressure in the fall and a little in the spring into a “full court college press” beginning in a student’s junior year and not being complete until they have been admitted – which for many, is not until the March of the following year, when “regular” decisions are released – nearly 18 months. Students who don’t know where they truly want to go, are made to feel that they are in some way socially lesser than those who apply ED, which can sometimes be for no other reason than they aren’t sure where they want to spend the next 4 years of their lives, and they don’t want to lock themselves into that decision.

Why would a seemingly innocuous process cause so much social, emotional, and psychological dysfunction in high school students? Attending college, especially for young women, has become a social badge of honor – something that students use as capital as they jockey for position within their hierarchy. The social dynamic between high school girls regarding college has always been tenuous and now the process is further stratified. The social implications on our young men and women are significant.

This social stratification has real-world consequences in the form of mental health – the pressure that I discussed earlier is important – we want our students to feel motivated to work hard and do their best to be successful. What we have created is a process in which students are working hard, and despite that effort, are being sent a message that they still aren’t good enough, because they need to work extra extra hard if they want to know where they are attending in December. Regular students – students who have otherwise made significant academic achievements, now are led to believe that unless they get in early to a school, that achievement somehow doesn’t matter.

What message are we sending to our students? The result is clear – rates of anxiety and depression never seen before, suicide rates NEVER seen before. Social struggles that are compounded by our lightning-speed information age. It’s time to reconsider what the priorities are for students who want to go to college. The adults working with these students need to send the message that overall fit – academic, social, emotional, and psychological – for a school must be the priority. Parents only want the best for their children when finding a college to attend; unfortunately, our professionals tasked with guiding those students have lost sight of what “the best” means.