By Anjali Kishore

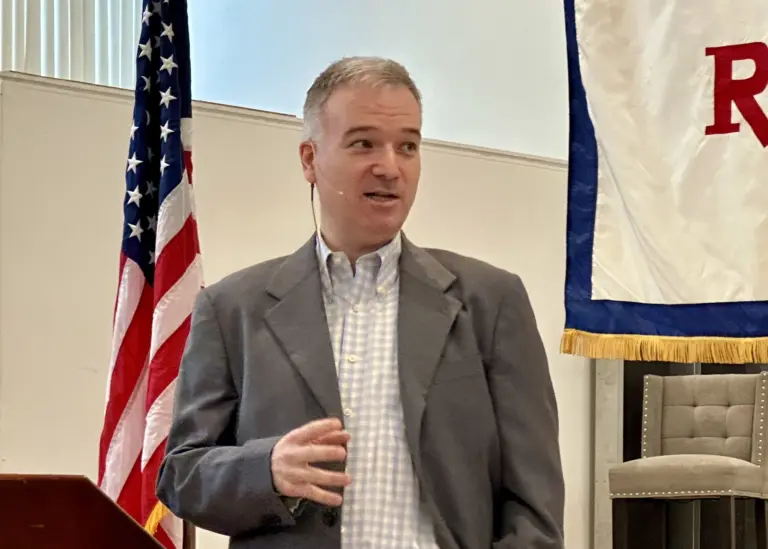

On December 17th, Greenwich High School stirred up a frenzy when word got out about a concerning social media post that was interpreted as a threat to the school. The post, and rumors concerning its content and validity, were widely circulated, creating quite a bit of confusion among students, parents, and other members of the school community concerning how to react to the perceived threat and what, exactly, was going on. The Sentinel had the opportunity to sit down with GPD Captain Mark Zuccarella to discuss school threats in the social media age, and get a bit more clarity on what exactly members of the community can expect from the police force, as well as school officials and employees, when it comes to school safety.

First off, Capn. Zuccarella made sure to emphasize the close working relationship that the police force has with school officials, saying, “We work closely in-hand with the Director of School Safety for the public schools, and we have worked with the private schools as well, especially when asked. Specifically, the Community Impact Section (203-622-3660) handles all the drills we do, as well as doing school assessments. They have specialized training in that, and can help a school if necessary.”

While there are a number of formal measures in place to prevent school violence – the Safe School Committee, which in any case include a “local police officer, local first responder, teacher and administrator from the school, a mental health professional, a parent or guardian of a student at the school, and may include any other person deemed necessary”, per the state government’s School Security and Safety Plan Standards, is an important part of the effort to stymie school violence, as are School Resource Officers, who use a triad approach in which they seek to balance duties as police officers, student mentors, and school employees – Zuccarella considers all members of the school community part of the team. “The kids have all been told how to behave on social media, and in the past, we’ve had students even correcting their own parents on social media. The students are part of the team – they’re not disregarded in the process,” he says, “The teachers and custodians and everyone are a part of the team, and the students are a big part as well – they’re told who to talk to, what to do if something is happening and how to get information out there. We’re not looking to punish people, we’re looking to prevent harm to people, and it has worked. A lot of information is shared with teachers at schools because of that relationship, and we always need to continue working on that relationship.”

Students can reach out to resource officers, trusted adults, and also use the high school’s Anonymous Alert software to raise concerns without making their identity known.

This information is critical to what the state of Connecticut calls the Multi-Hazard Plan, where the police and school officials seek to address not just violence itself, but factors that may contribute to violence. “In the past, we have found that we focus so much on the active shooter that we forget about all the other stuff that happens within the school that needs to be addressed,” says Zuccarella, referring to risk factors such as harassment and home problems.

According to Capn. Zuccarella, “The Secret Service and researchers have found that the best approach is to identify small, re-occurring points that might seem innocuous now but become signs after the fact. There have been signs, especially in Colorado, that were missed and that’s nobody’s fault, it was just the operating standard of the time. Now, we’re sure to take all threats and signs seriously. The School Resource Officers are active within the school with issues, complaints, and threats, to see if there’s any validity to it or if the student made the comment if, say, they were being harassed or had some other issues they might need assistance on.”

These small concerns can climb up what is widely known as the Continuum of Violence: “First what you’ll see is a child who has a lot of anger, lots of screaming and yelling. On the other end, there’s actual harm to others,” says Zuccarella, “But in between them, you might have a child who verbally threatens other people, or damages other people’s property, or self-harm. These are the things we have to pick up on – I’m in no way saying people who self-harm pose a threat in a school, but these are the things we need to pick up on and understand why they’re doing these things. If we have a kid who’s in school going around damaging things, we’re not saying he’s going to be a school shooter, but we want to address that and find out where this anger is coming from, and how we can better make it so that this child’s educational experience is positive for themselves and other students.” At GHS, when a threat of harm or self-harm is identified, a threat assessment is done to determine what approach should be taken: the police are also typically alerted, even if they don’t necessarily play a role in addressing the situation. This is part of the robust flow of information between the students, school, and police which allows for the effective addressing of school threats.

The importance of open communication is something that Zuccarella emphasizes, especially when discussing the December 17th incident at Greenwich High School where many parents were in the dark and, after the fact, became frustrated with the handling of the situation. In this case, he suggests open communication with the school: “The parents need to be involved with their child’s education, and know the plans and policies that the school has. They have the right to know what Safe School Committees are doing, and if they have a question or concern with what the school is doing they can contact the school; at the high school, contact the House administrator. They’d be more than happy to discuss with parents why they do what they do, and what the role is for the police officers. If anyone has questions about how we work with the schools, they can contact the special victim section (203-622-8030) and talk to the section sergeant.”

Social media has also allowed for a much larger flow of information, which has greatly impacted the methodology behind and approach to school safety in positive and negative ways: according to Zuccarella, “In the negative sense, something that is mundane and not an issue can turn into a major concern. The problem is that not everyone’s on the same page with social media – one of the big things that we’ve been working with the Board of Education on is that, in the event that the school is potentially in danger, not having parents come to school because the last thing we need is more people getting in the way of the first responders. Everyone’s cognizant that your child is here and if something’s happened, your first instinct is to get your child out, but it can get in the way. Conversely, the use of social media is good because it gives us information and data that tells us things. There’s also the positive that we can get information, and get accurate information out there fast.”

In order to effectively use social media, Zuccarella recommends parents and students taking a step back and consider how the information they share may impact a situation, as much of the confusion surrounding school threats comes as the result of too much information that hasn’t been confirmed. “Instead of posting thoughts about “why did this happen, why did that happen”, just ask,” Zuccarella suggests, “We’d love to tell you. I’d love to broadcast to the world everything that’s happening, but that’s impossible because sometimes people don’t get it, or just don’t care. People just need to talk to their schools and ask them, that’s the best way. For example, one thing that causes a lot of problems is whether the school is in lockdown, shelter-in-place, or a secure building; people like to say the school is locked down but GHS wasn’t in lockdown in this most recent case, but each term has a different meaning to it, and different way that it’s addressed to address the hazard while not interrupting the school’s educational goals. If people want to know, they should contact the school, and the school would be more than happy to explain why they do what they do.”

For more information, you can view Greenwich Public Schools’ safety plan here or contact phone numbers above

To receive quick and reliable information, connect with GPD on Twitter and Facebook