By Anne W. Semmes

Greenwich grown Heather Ewing has distinguished herself as historian of art, architecture, and American history. Her biography of the benefactor of the Smithsonian Institution, John Smithson, tells the story of a man who never set foot in America but believed in its democratic ideals. Her history of Andrew Carnegie tells of this immigrant, industrial giant and pioneering philanthropist. And now Ewing has taken 500 years of American history and divided it into seven “moments” of arrivals to its shores to best explore American identity and immigration through the lens of artists in her “Arrivals” exhibition now on view at the Katonah Museum of Art.

Ewing, who lives in New York where she is Associate Dean for Administrative Affairs at the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting & Sculpture when not visiting her dad Ted Ewing in Greenwich, recently gave this reporter a tour of her guest curated show “Arrivals” in Katonah.

It began with the first moment of arrivals, in 1492 with Columbus and two striking artworks, N.C. Wyeth’s “Columbus Discovers America” and “Columbus Day Painting” by New Haven artist Titus Kaphar. Kaphar has reimagined John Vanderlyn’s 19th century painting found in the U.S. Capitol by binding the featured Spanish colonizers with blank canvas to shift the gaze to the indigenous figures in the background.

Ewing described her aim was to “help us have a way to understand that America is not just a nation of immigrants. That’s what we’re told…but it is much more complex and difficult. It’s part of why we’re having so many problems right now as a country because we haven’t ever really faced the difficulties and the complexities of our history.”

So, do define immigrants as compared to non-immigrants she is asked. “So, immigration is somebody coming here from somewhere else – it’s generally voluntary…And that is certainly what’s at the heart of this idea of us being a nation of immigrants, all these people from all over the world. And it’s incredibly inspiring. But we also have to remember that some of us are descended from people who were of Anglo origin, who came here as settlers to colonize the country…And then obviously are the native peoples who were already here. And also, the people who are descended from those who were brought here in chains as enslaved people from Africa.”

Yes, most moving in the second moment, “The Middle Passage” (from 1619-1808), is that historic outline of the African slave ship Brookes, “with its harrowing schematic revealing the tight packing of humans.” “It carried more than 600 on at least one journey,” said Ewing. “They would have been stacked in layers and all chained together…And so contemporary artists have very powerfully taken that image and reimagined it and use it in different ways.” Such as in those two black girl figures sculpted by Vanessa German placed on a skateboard with slave ships on their heads.

The third moment marks the arrival of the pilgrims on “The Mayflower” in 1620. “All three of the moments in this room,” told Ewing, “Are rooted in this time period, much before the creation of the United States. But they’ve shaped very much our United States today. And so, I wanted to look at how artists are helping us to see these stories in fresh ways and to think about them differently.”

Ewing is particularly moved by Indigenous artist Cannupa Hanska Luger who enlisted artists from tribal nations across North America and the Pacific “to investigate and interpret their lives as survivors of settler colonialism” in a documentary film created by Razelle Benally. “People can check out this beautiful project online at www.sttlmnt.org.”

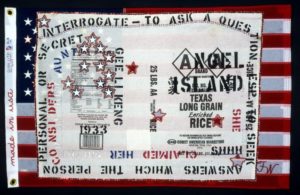

The fourth moment of “Ellis Island and Angel Island” (1891-1924) brought the surprise of that less known San Francisco gateway of arrivals from Asia. Artist Flo Oy Wong’s work shows an American flag hand stitched with a rice sack, “a symbol of a traditional food source that sustained her family in hard time.” “Oy’s story,” shared Ewing, “has to do with the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and it meant that she has a different life than her sister and her mother because her mother was only able to enter the country as her father’s sister.”

A photograph by famed photographer Lewis Wickes Hine entitled “Climbing into America, Ellis Island. 1908” captures an elegant man with mustache turning to look at the photographer carrying his suitcase.

World War II as the fifth moment brings artwork created by Roger Shimomura who was imprisoned as a child in a camp holding Japanese-American citizens in Idaho during the war. In his cartoon-like color lithographs, “he’s imagined behind the barbed wire,” noted Ewing, “all these very American people of Japanese origin and Mickey Mouse incarcerated, and outside the barbed wire Kabuki actors from the 18th century.”

The sixth moment is dated 1965 because of the landmark Immigration Act of 1965 that ended discrimination based on place of origin that opened this country to arrivals from all over the world. “It overturned all of these extremely restrictive racist exclusion policies that we had from the 1920s that dominated most of the 20th century.”

Ewing pointed to a small Rothko Room with its painting as part of the Museum. “It’s technically not part of Arrivals,” she said, “But I wrote a label for it because Rothko was an immigrant. And I think it’s really fascinating that Abstract Expressionism, which we think of as this very American form of modern art, was essentially the product of a whole bunch of immigrants.” AKA, Ashille Gorky, Willem de Kooning, and Hans Hoffman.

The seventh moment is “Today” and one photo grabbed the eye of a cowboy with eagle wings pulling on a giant slingshot. It’s entitled “The Wild Blue Yonder” by artist Javier Piñon.

For anyone wanting a looksee at a masterful timeline of the history of immigration and those different arrivals it’s all there on the walls of the Museum’s Atrium, courtesy of contributing artists and the Immigration and Ethnic History Society. “It starts with the Naturalization Act of 1790, the first law to define who could become an American citizen (‘free white persons’),” said Ewing, “and ends with some of the rules implemented by the Trump Administration, like the so-called Muslim ban. These laws have profound real-life consequences for all of us, but a timeline is a pretty impersonal way of looking at history.”

So, this reporter had to ask Ewing with her deep involvement with the Smithsonian Institution had those years especially nourished her? “Absolutely. And the way that the Smithsonian has also grown and expanded to think of how they encompass and represent all Americans has been a huge influence and learning for me.”