By Anne W. Semmes

Hidden away on a rise of land that overlooks Mianus Pond in Cos Cob is an historic mini-artist colony called Lia Fail. It came into being soon after the heyday of the Cos Cob Art Colony of American Impressionists in the early 1920’s, when David O’Neil bought up 20 acres in 1926 of that high rising land he named Lia Fail, with its sizeable “Stone of Destiny” marking the entrance signifying the birthright of O’Neil’s ancient Irish clan.

O’Neil was a successful businessman but also a published poet who would celebrate his new land with a line of poetry: “At Lia Fail the spirit of wonder possesses my dreams when summer foliage closes me in – though winter comes and lays all bare, the mystery only deepens.”

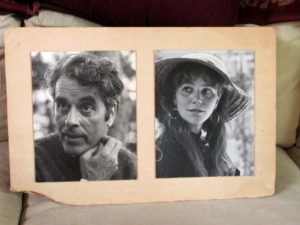

O’Neil would physically support his architect-sculptor son Horton’s dream to build a marble amphitheater on those 20 acres that would bring performances of Shakespeare and modern dance. His daughter Barbara as an actress would star in the film, “Gone With the Wind.” Horton’s wife, Madelyn, would act and dance on that amphitheater. And then Madelyn’s painter brother, Jack Phillips (John C.) would arrive from his artistic-rich life and move into a cottage on the property made empty with the death of the senior Mrs. O’Neil. Then along came Florence, Jack’s new wife, also an actress and musician, later teacher of poetry at the Cos Cob School.

Florence, widowed in 2003 with Jack’s death, has watched over the great demise of that marble amphitheater, partially transplanted to Sarah Lawrence College, kindness of Cos Cob artist friend Josie Merck. Florence has also watched over the significant work of her husband of nearly 40 years. When she shared she would be dismantling Jack’s studio to store properly the hundreds of his works left behind, this reporter jumped at the chance to see inside that studio prior to its dismantling.

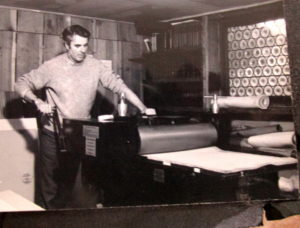

Inside the studio, next to Florence’s cottage, was Jack’s “huge” printing press Florence tagged “his Steinway,” though now fairly obscured with the stacks of his prints and paintings. “He did his big prints on this, like the one at the Greenwich Historical Society,” she told.” A year ago Florence had donated Jack’s print of “Horseleech Pond I. “That Pond,” she says, “is in Truro on Cape Cod where we have lived off and on.

“He always loved printmaking because he felt that the track of the animal was more exciting than the animal itself. He always wished that the printmaking process was simpler than it had been through the ages, with acids and tools. So, in the 1970s, he invented a way of printmaking – intaglio – that was as free as painting.” With intaglio the image is incised into a surface and the incised line or sunken area holds the ink, or “The plate bites into the paper,” noted Florence.

A tour of Jack’s prints on display in Florence’s cottage followed. But larger than life over a piano was Jack’s luminous painting of “Maine Woods.” Surely it shows that early study time he had in Paris with French cubist painters Fernand Léger and André Lhote.

But everywhere Jack’s intaglio prints abound with scenes of his beloved Truro campgrounds, an art colony itself over the years. There’s “Salt Marsh Creek,” and another “Horse Leech Pond” and “Tidal Pool.” “He had a gallery on the Cape for quite a number of years,” said Florence. “And he had a number of shows there.”

In 1970, Jack shared exhibit space with his sculptor brother-in-law Horton O’Neil in Greenwich Library’s Hurlburt ([now Flinn] Gallery. “Those was Jack’s early prints and Horton’s sculptures, which he was just starting to do,” noted Florence. [This reporter is proud to have been given Horton’s revolving bronze sculpture, “The Judgment of Paris” by his widow, Madelyn.]

Two years before Jack died at age 94, he had an impressive “Century Masters” show at the Century Club in New York City highlighting his long career in printmaking. A line in the show’s introduction – “John C. Phillips: Printmaker,” states, “Phillips’ intimacy with nature was so acute that he did not need to copy it.” And “his work has always been rooted in the New England landscape.” But for 30 years after graduating from Harvard, Jack had lived long periods in Europe in a most bohemian life.

That life is newly portrayed in the book, “Upper Bohemia” written by Hayden Herrera, Phillips’ daughter by an earlier marriage. “These so-called upper bohemians,” Herrera writes, “had privileged childhoods but rebelled against their parent’s life…Their lives were full of adventure and drama, mixed with chaos.”

By 1964 when Jack met up with Florence Hammond, daughter of a distinguished Harvard classics professor, he was divorced from his fourth wife, the widow of artist Arshile Gorky, having presided over a total of six daughters, four of whom were his own. With Florence he became happily grounded in Cos Cob and Cape Cod for those nearly 40 years, printing and paining away.