Finding the Lost – and Found – to Honor on Memorial Day

By Anne W. Semmes

When Memorial Day arrives, the thought comes to get up close and personal with those in our town who have given their lives in military service in wartime for this country. I imagine going to a place like that wall of names for the Vietnam War in Washington, where you can pass your hand over the names, and feel their sacrifice.

What I find in Greenwich are individual plaques of names in Town Hall, listed war by war, beginning with the Revolutionary War. That earliest war had recognizable Greenwich names like Knapp and Close. The Civil War had Meads and a Ferris. World War I had that famous pioneer aviator Col. Raynal Bolling, whose statue overlooks Greenwich Avenue. Bolling was the first high-ranking American officer to die in combat in WWI. He was a founder of the US Army Air Service which became the US Army Air Corps in World War II, in which my father Thomas J. Semmes served as Intelligence Officer, and fortunately, he came home.

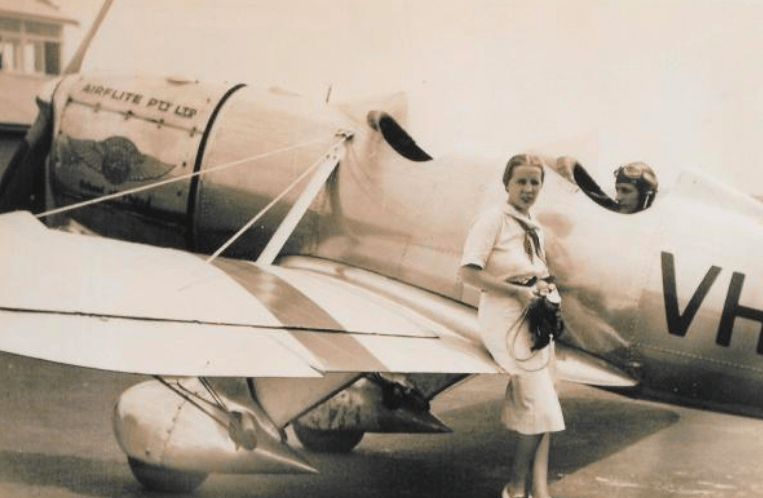

So it was that another pioneer aviator name jumped out of the World War II plaque – Wilbur “Billy” Cummings, Jr. He was a member of that famed Flying Family of Greenwich that took to the air in the mid-thirties: Marion Engle Cummings, son Billy, and his younger sister Molly Cummings Minot Cook – still wonderfully with us at 99. “My brother was my idol,” she has written.

Billy had lived out his dream to travel to the Orient after Harvard, becoming one of the first Americans to visit Tibet in 1938 before he entered WWII in 1942 as a Navy Pilot. His job was to ferry planes where they were made in Columbus, Ohio to England. He was flying a brand new SOC3 observation plane that was overloaded with equiptment when he crashed during takeoff and was killed.

That much missed brother put me in mind of another much-missed brother of our own Gloria Heath, who at 95 years of age carries the fame of being one of 100 women who have most influenced the development of aviation. Gloria served as a pilot of Women Airforce Service Pilots, or WASP, in WWII and flew B-26 bombers used for target practive. she was turned on to flying back in college by her older brother Royale Vale Heath. “He was my hero,” Gloria has shared. Royale was a China/Burma/India pilot in WWII when he was killed at age 28.

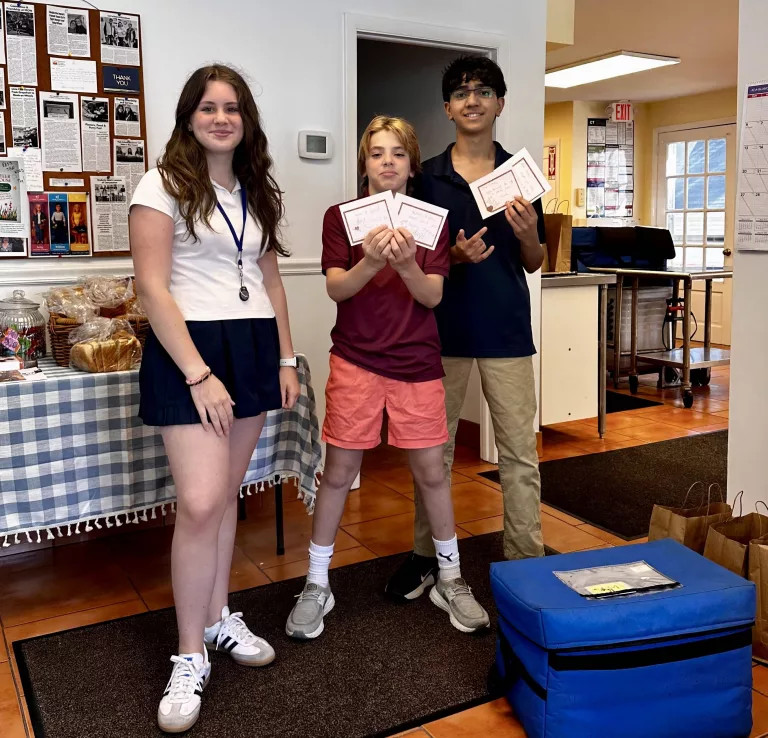

We have the Oral History Project (OHP) of Greenwich to thank for recording the narratives of Molly Cummings Minor Cook and of Gloria Heath. I have also had the privilege of interviewing these pioneering aviators, to learn more about their valiant brothers, and thanks to the OHP we have the extraordinary narrative of Alexandra Clarke Spann.

(1903-1977) that brings us our wartime “found” story. Spann’s father, John A. Clarke M.D. was a distinguished doctor in town, serving the Greenwich Police Department. (Each year the Lions Club honors an outstanding Greenwich Police Officer with the John A. Clarke Award).

Spann’s discourse is a fascinating walk down memory lane in Greenwich. It includes her telling about meeting Ernest Thompson Seton (ETS) when she was in elementary school. She would sit at the famed storyteller’s feet when in wintertime, at the “Armory” on Mason Street, “he’d tell us stories” like “Raggylug”, her favorite, about “a rabbit with a ragged ear”.

But her “most dramatic” memory as an elementary student was when she attended a World War I memorial service at the old Havemeyer School for the brother of “one of our favorite mail carriers, Johnny Lockhart.” Lockhart was informed his brother had been killed “in a division in Europe that was almost completely annihilated.” Spann, *just big enough to carry a small flag “over her shoulder, was singing “America” and prating with the others when who should appear but the “dead” brother!

“Dead silence. You could feel it. It pressed on you. Then all pandemonium let loose. People shouted, stamped, whistled, threw their hats in the air. Even the flags went up.”

“Did he know this was his funeral service?” the interviewer asked Spann.

“No, he didn’t. Somebody told him there was a meeting in the Havemeyer Building. He just walked in cold.”

Postscript: “A Doctor’s Daughter, published as an OHP hardcover “red book” in 1985, recounts four separate interviews, what it was like, growing up in Greenwich in the early days of the twentieth century.