By Clay Kaufman

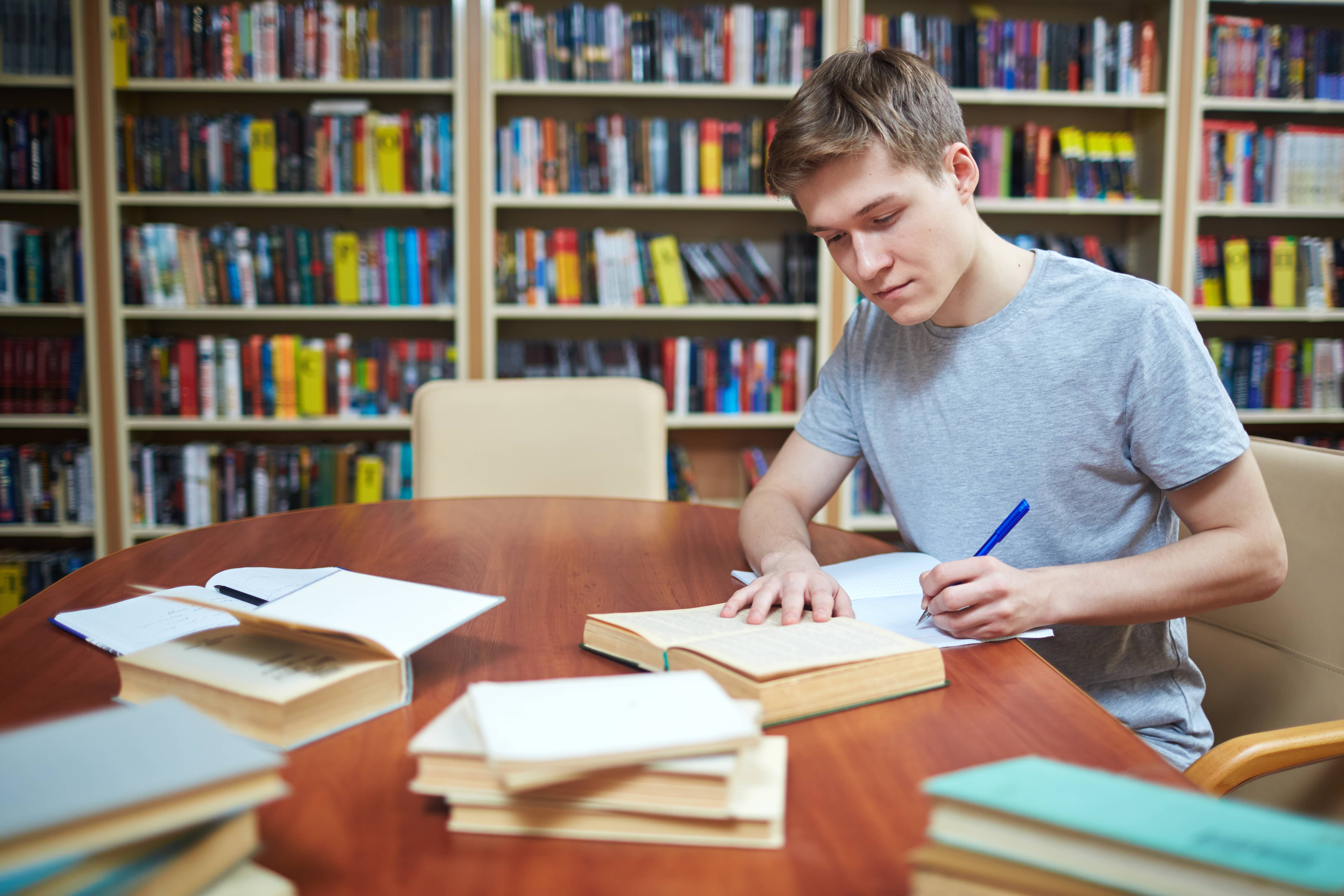

Imagine being offered a job in a field you disliked, that required skills you didn’t have. How much money would it take to persuade you to take the job? For most of us, the salary wouldn’t be worth it.

But now imagine a job that most of us probably have: one that requires skills you possess—your strengths—along with some less attractive responsibilities. The part of the job that draws on your strengths probably makes up for the rest. And the more time you are able to devote to your strengths, the happier you probably are. After work you can come home and, hopefully, put the less attractive parts of your job aside until the next day.

Now consider teenagers in the same situation. We constantly remind them of the importance of doing well in school—their current “job” —even in subjects they don’t like, which might be quite a few. They have to work all day in school and then come home and complete work in all those subjects each night. What gets them through their day? So many students I have worked with over the years have told me that their favorite subject or favorite teacher helps get them through the hard parts of the day, and then they look forward to basketball or lacrosse practice or chess club or some other activity they love, such as playing video games with friends online.

Their strengths are—and typically will be—related to their area of focus in college and in life. So it’s tremendously important to help our children discover their strengths at an early age, to help them find the joy that gets them through the day. Sometimes that means we have to let them try many different sports or activities until they find what they love, even if it means dropping out of unsuccessful activities and losing an occasional enrollment fee. The story is that Ansel Adams, the famous photographer who struggled in school due to dyslexia, had an awful 7th grade year. That summer his uncle handed him a camera and said “try this.” Well, that worked. Our children’s strengths may not be what we wanted or expected, but by encouraging them, we can help them feel confident, happy and fulfilled. Choosing one strength to the exclusion of all else (365-days-a-year baseball or 24-hour-a-day video games) isn’t the answer, but devoting significant time to their strengths, research shows, makes a difference.

I was fortunate that in my first teaching job was at a private school in Washington DC, I met an extraordinary educator, Elizabeth Ely, who founded The Field School based on the belief that teaching and learning should be student-centered and should help children find their strengths. She required students to take an arts elective every year, trying out different activities to see if any clicked. She also required students to try a sport. And she made accommodations in the curriculum if students had an area of interest they wanted to pursue. I remember one conversation particularly, one that involved a student’s strength. We had a student who loved basketball and loved being on the team. He was a great teammate and practiced whenever he could. Basketball clearly brought him great joy. But he struggled in history and his parents simply couldn’t get him to get his history homework done. They proposed banning him from the basketball team unless he did his history homework, and I remember that a group of his teachers agreed, reluctantly. But Elizabeth didn’t agree. She said we would not be removing him from the basketball team: she explained, “Basketball is what he loves, what helps get him through the day. Do you think that if we take that away, he will immediately spend all of his new free time working on history? No, he’ll be resentful and probably dig in his heels. Let’s find out what makes him dislike history and fix the problem. Not doing the homework is just a symptom.”

As a young teacher, I was amazed. Almost everyone I knew grewing up had been “punished” at one time or another by having a favorite activity taken away. And they all were resentful. Elizabeth recognized the power of acknowledging and encouraging strengths.

Now, if a child is motivated but simply too busy to get work done, then freeing up time certainly makes sense. But I have seen for many years that you cannot force someone to be motivated.

So what can we do? We can hand our children a camera—or a baseball, a chess board a favorite novel, a set of Legos or a science kit . We can see what works, and encourage their strengths, which may well prove to be the foundation of their success and happiness in life.