Anne W. Semmes

Sentinel Columnist

If ever a human was lifted to heaven on wings it must have been the esteemed ornithologist Chandler “Chan” Robbins, who died on Monday, age 98. Surely what he did in his lifetime for the protection of birds would warrant such delivery to the heavens.

Count his early concerns about the effects of DDT on birds and how it affected bird populations that fed Rachel Carson’s research and led to Chan’s conceiving the Breeding Bird Survey. Picture him that first year, over half a century ago, on an early May morning in his native Maryland, on the edge of a forest, leaning in to the dawn chorus, cupping his ear to amplify bird calls, then marking his charts. That survey, that taking a section of forest and counting the birds by sight and song, is now the worldwide model for monitoring bird population trends.

For many survey volunteers—in our town, Cynthia Ehlinger, Ted Gilman and more, and once yours truly—the survey became a springtime ritual. Count former President Jimmy Carter and wife Roslyn as volunteers.

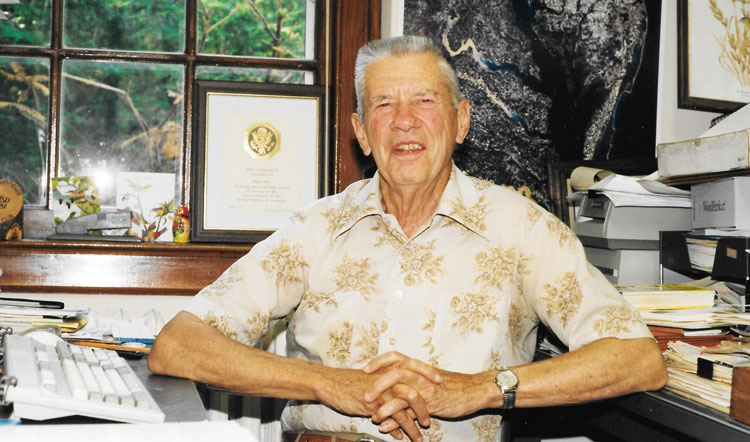

For all his long life, Chan worked for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife’s (USF&W) Migratory Bird Population Station in Laurel, Md.—now called the U.S. Geological Survey’s Patuxent Environmental Science Center. It was there I visited him some 20 years ago and saw what a gentle and wise scientist he was. I wrote afterwards for Living Bird magazine about his 50th anniversary celebration by the USF&W at Patuxent, where he was presented with a watercolor of his favorite bird—a winter wren.

For many, it was Chan’s co-authoring of the Golden Guide to the Birds of North America, known as the “Robbins Guide,” published in 1966 and selling many millions of copies, that first primed beginning bird watchers to birdsong with its first-time sonograms. Roger Tory Peterson once said of Chan that he had the best bird-listening ears of any birder he knew.

In 2013 Chan came in his wheelchair to Greenwich’s Audubon Center—as cheerful as ever—to speak. He addressed how the rising deer population was bad for birds and spoke of the great decline of the wood thrush, how commercialization of its wintering grounds in the tropics was taking its toll.

But Chan retained his optimism. To questions I’d earlier posed to him about when would our eastern birds learn to identify and reject the alien cowbird eggs in their nests, he’d answer, “Give them time. Eastern birds have only been exposed to cowbirds for a few decades. Expect some changes by way of natural selection over the next 1,000 years.”

Patience and perseverance were key to Chan’s modus operandi.

Last year I had the great joy of celebrating the long-living Chan alongside another long-living legend, Wisdom, the Laysan albatross, the oldest recorded banded bird in the wild. Chan had first banded Wisdom in 1956 in the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge, located in the farthest reaches of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Wisdom, a female, was figured to be five years old then—Chan was 37. Chan would revisit Wisdom twice more, the last time in 2002, when he was age 81.

With Wisdom now thought to be 66 and still bearing chicks, her survival is incredible! She’s in the air for 90 percent of her life with enough frequent flying miles said to equal six round trips to the moon! In my story for Living Bird I asked Chan just how is it that Wisdom had survived tsunamis and not ingested the deadly and prevalent plastic afloat on the sea.

His answer was simple. “I like to think in all her years Wisdom has learned to avoid most of the hazards that threaten sea birds… She is demonstrating that the Laysan albatross has an exceptionally long reproductive life. Indeed, Wisdom is exhibiting a life pattern considered more similar to humans than virtually any other animal.”

And here is where I steal a line just found on Facebook written by naturalist and author Kenn Kaufmann: “If birds were applying names to people, instead of the other way around, the albatrosses probably would have called [Chan] “Wisdom, the human.”