By Tim Dumas

Contributing Editor

Early September, and already the leaves have begun to fall. Susan Wohlforth walks up a pathway on a bluff overlooking Cos Cob Harbor and stops, a little dazed, when she beholds the newly installed glass towers glittering in the sunlight. “I haven’t seen these yet,” she says.

Workers from Fred N. Durante Jr. Landscape Services kneel upon the circular terrace surrounding the 12-foot towers, fitting together the last of the black granite paving stones. A kindly foreman, Sal Longo, observes the well-dressed woman in dark sunglasses who has appeared at the perimeter, and comes over to greet her. “There’s my husband’s name,” Susan tells him. She points to the tower on her left—a translucent representation of the World Trade Center’s South Tower. On Sept. 11, 2001, Martin Phillips “Buff” Wohlforth, 47, managing director of the investment banking firm Sandler O’Neill, was at work on the 104th floor when United Airlines Flight 175 out of Boston slammed into the building some 20 floors below.

Sal looks at Susan and says, “Would you like to come closer?” Not wanting to trouble the workers, she demurs, but Sal leads her through the work zone anyway, to a granite bench at the edge of the terrace. “Here, come sit down,” he says. The bench has been warmed by the sun so that it feels almost soft. Sitting here, on the high ground of Cos Cob Park, there’s a grand vista of water and marsh grass and seagulls wheeling above and below the bluff.

The 9/11 Memorial Greenwich opened to the public this morning—14 years to the hour after the terrorist attacks commenced. The glass towers stand atop a knoll as the memorial’s quietly dramatic centerpiece; they look delicate as they glimmer and shimmer, but they’re built to withstand hurricane-force winds and hostile winters. An American flag motif is frosted into the glass, and within the stripes of the flag appear the names of the 32 Greenwich residents, former residents, or family members of residents who died in the towers. A 33rd name, Donald Freeman Greene, is set in among the paving stones, representing the Greenwich man’s death aboard United Airlines Flight 93 in the Pennsylvania countryside.

“It’s absolutely beautiful,” Susan said of the memorial and its rich landscaping. “I love the breeze. I love the comfort. I love the peace.”

She and Buff met some 50 years ago at their tiny Catholic elementary school in Bergen County, N.J. “I had a crush on him in the fourth grade,” she confesses. Then they went to different schools and did not see each other for a long time. Eventually she went off to Italy for grad school and a job at Gucci. “I came back and he called me and we went out. I said, ‘So what happened, you went through your little black book and I was the best thing in it?’ He goes, ‘Yep.’” They married and had a daughter, Chloe. She was 16 and a student at Greenwich Academy when her father died in the South Tower.

“I say that I’m one of the lucky unlucky ones,” Susan says. “I’m unlucky that my husband perished on 9/11, but lucky that he was found. So I buried my husband. I had a coffin with a flag on it and my husband in it.” Others, she notes, have nothing, no remains on which to focus their grief, no sense of completing the death ritual. Memorial sites are what they do have. Still, this new memorial is vitally important to Susan, too. “I will come here when I need something bigger than my own private space at Putnam Cemetery,” she says. “That happens to me, believe it or not, more now than it did before. I actually feel much more connected here. I share something with all these people and their families that I can’t get anywhere, to be honest with you, except right here.”

Another name on the memorial is Jason Sabbag. At age 26, he was witty and cultured, a champion tennis player, and a gifted financial analyst at Fiduciary Trust International. Jason had been signing a contract with a German counterpart in a conference room on the 94th floor of the South Tower at 8:46, when American Airlines Flight 11 struck the North Tower. The Port Authority told those in the South Tower to stay put until further notice. But Jason’s colleagues on the opposite side of the building, having a clear view of the catastrophic damage, disregarded those instructions and made their way down. At 9:02 the Port Authority ordered the evacuation of both towers, and at 9:03 the second plane struck.

That morning, Jason’s father, Ralph Sabbag, had commuted from Greenwich to his fuel brokerage office in New Jersey. When he arrived, he learned that the World Trade Center had been hit. “We couldn’t get in touch with Jason because he was in the conference room, and the doors were closed,” Ralph recalls. “So I panicked and said, ‘Okay, let’s go back to Greenwich.’ On the way, I was passing Manhattan, and here was the plane going to hit the South Tower. I was looking at the plane going low, then straight toward it. Then boom. So I saw it live, the plane that killed my son.”

This summer, as the 9/11 Memorial progressed, Ralph could be seen there every day.

“They did a fantastic job, just superb,” he says, sitting at the dining room table of his condominium in Cos Cob. There are photos of Jason everywhere, to give as much of a sense of his presence as possible. “Now we don’t have to drive to New York. For us, the ceremony is not going to be there any more, it’s going to be right here, close to home. That’s the point. You’re sitting there, you see the two glass towers, you see the harbor, and the boats, it’s just gorgeous. You can sit down and read or think. It will bring you all kinds of memories.”

Like what? “Here’s a little story,” he says. “I’d been playing tennis with Jason from the start, but he had gotten too good for me. He became so good he was No. 61 on the East Coast. It was impossible for me to win even a game. It was just 6-0, 6-0, 6-0. One time I had my whole family at the Stamford Yacht Club, which we belonged to at the time, and they came to watch us play. I won the first game, and I was so excited. Then I won the second game! Then Jason came to the net and he said, ‘Dad, I just want to tell you. Happy Father’s Day.’”

Ralph smiles at the memory, but there is sadness in the smile. When he speaks again he is not talking about tennis anymore. “He was too good, my son. He was too good.”

Earlier Memorials

Ralph Sabbag is a member of the Greenwich Community Projects Fund, which, beginning in 2010, began an effort to build a new memorial. It would not be the first 9/11 memorial in town. There are several plaques and benches, and two substantial memorials that draw varied reactions. Last year the Glenville Fire House acquired a 1,700-pound beam from the World Trade Center and planted it upright in the grass. It is an arresting object, to be sure—rusted, brutish, and vividly reminiscent of the destruction. Susan Wohlforth, for one, sometimes averts her gaze when passing it.

Until now, our most complete 9/11 memorial had been out at Great Captain’s Island—a bronze plaque on a granite stone in the shadow of the old stone lighthouse. The view sweeps down to New York. The site is beautiful and conducive to reflection. But this memorial, erected in 2009, did not escape controversy. Whose names should be inscribed on the plaque and whose should not? The original thinking had been that only the 16 who resided in Greenwich on 9/11 should be listed. That meant leaving off victims who had grown up or spent time here, like Teddy Maloney, Robert Walter Noonan, and Jason Sabbag. But Ralph Sabbag and others family members spoke up, initiating a public quarrel they believe should not have been necessary. In the end, 26 names adorned the memorial at Great Captain’s Island.

“Now this is forgotten,” Ralph says with visible relief.

What can’t be forgotten, though, is Great Captain Island’s remoteness. One can get there only by ferry (with a beach card), and the ferry lands on the “wrong” end of the island, so that visitors have to trek across a low-lying land bridge that gets partially submerged at high tide. “When we came back from a ceremony there, it started to be high tide, and we had to roll our pants up,” Ralph says with a laugh.

It’s not the sort of place one can up and visit when the mood strikes.

“It’s gorgeous, but nobody can get to it,” Susan Wohlforth says. “When people realized it was so inaccessible, I think that’s what really drove this memorial. So there are other memorials here—but for me, this is the one.”

‘A huge responsibility’

Memorial-making might seem a simple matter. It isn’t—not conceptually, not structurally, not politically, not financially. The great case study is Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. When Lin’s concept—the now-familiar black granite V in which the names of the dead and missing are engraved—was judged the winner of an open competition in 1981, a fury erupted. The writer Tom Wolfe called the design “a tribute to Jane Fonda.” Others described it as “a monument to defeat,” “a black gash of shame” and “an open urinal.” Today the memorial is almost universally beloved. One thing that makes it so is the careful thinking that went into it. As we read the rolls of the dead, we also see our own dark reflections, and this double image seems to say, “They are us, we are them.” Thus fused, we cannot help but remember our collective loss.

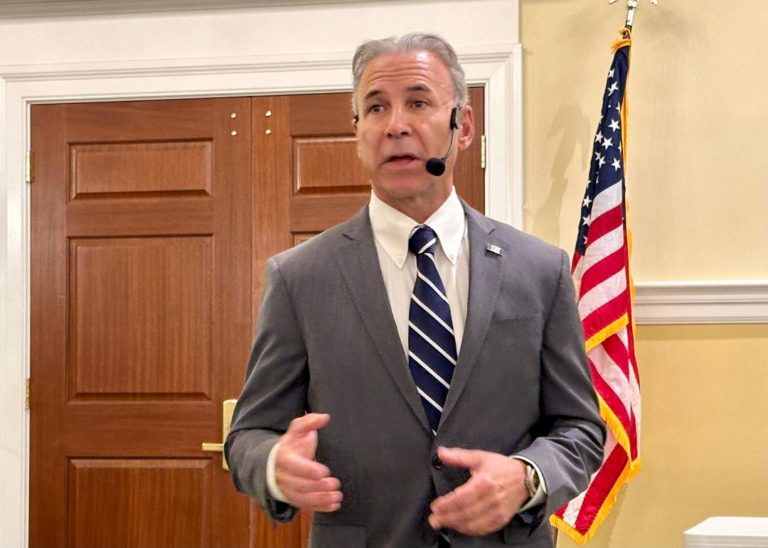

In 2010 Charles Hilton Architects of Greenwich was selected to design the 9/11 Memorial Greenwich. Chuck Hilton, the firm’s principal, took on the assignment with some anxiety. It wasn’t simply that Maya Lin and others had profoundly changed serious memorial design. (A heroic figure in bronze no longer cut it.) It was that reactions to 9/11 were so varied, so personal. What would the families say? “There you are, standing up in front of them with your idea, and they have teary eyes and they’re holding their breath about what you’re going to say,” he remembers. “And you’re hoping that they’re getting the meaning that you’re trying to give it. It was a huge responsibility.”

For his design, Hilton drew inspiration from the Towers of Light Memorial more than the Twin Towers themselves. “I remember, after Ground Zero was cleared, seeing those Towers of Light, and how ethereal they were,” Hilton says. “The towers were back, but they had this kind of ghost-y effect. They were kind of there and not there at the same time. For me, that was very powerful. And I thought, ‘I wonder if we could capture this in some kind of material form.’ The element of the glass towers was born out of that.”

For his design, Hilton drew inspiration from the Towers of Light Memorial more than the Twin Towers themselves. “I remember, after Ground Zero was cleared, seeing those Towers of Light, and how ethereal they were,” Hilton says. “The towers were back, but they had this kind of ghost-y effect. They were kind of there and not there at the same time. For me, that was very powerful. And I thought, ‘I wonder if we could capture this in some kind of material form.’ The element of the glass towers was born out of that.”

Hilton had hoped his towers—made of low-iron glass that will not discolor over time—would be softly illuminated, but that part of the plan did not survive the approvals gauntlet. At least for now. “Some day, if that changes, we could have lights at night. It’s not going to be bright—it’s just going to be this really cool glow.”

In contemplating the design, Hilton also remembered the impromptu memorials that went up near Ground Zero after the attacks. “There were these memorial walls with flowers and people’s names and little notes stuck in, and little flags. All these little symbols were incorporated. So the towers we’ve designed, we draped them with a motif of an American flag, and the victims’ names from Greenwich in the flag. We’re creating our own memorial wall of flags and names, kind of recalling those makeshift memorials that happened on the site.” (To carry out the idea, Hilton enlisted R.G. Hull, an architectural glass specialist in New Canaan, which silkscreened the flag motif onto the glass using a ceramic paint or “frit”; and Ferra Designs in Brooklyn, which assembled the towers from the glass panels that Hull prepared.)

As a setting for the towers, Hilton designed an abstraction of the World Trade Center Plaza—the black granite terrace—with two spiraling walkways leading up to it. If you were to see the walkways from above, their design would resemble the mathematically perfect curve of certain seashells.

James Ritman, co-president of the Greenwich Community Projects Fund along with Demi Ferraris, remembers when the design was unveiled to the families a little over two years ago. “They were brought to tears,” he says. “They were 100 percent unanimous—they loved it. There was not one negative comment, not even a little suggestion about what to do differently.”

A Vision Made Real

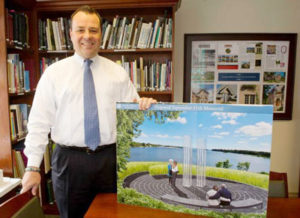

Even as the concept came together, though, there were problems. How would the Greenwich Community Projects Fund raise the enormous sum—$750,000—needed to bring the memorial to fruition? Where was the memorial going to be situated? (A couple of years ago, during its transformation from power plant to public space, Cos Cob Park had all the charm of a city dump.) “The project was languishing,” recalls Peter Barhydt, who would soon be called in to reinvigorate the team and rally the community. “They were even talking about giving the money back to people who had donated.”

Jimmy Ritman remembers those days all too well. “You’re looking at the situation, and there’s no location, no money, no real support, and you’re wondering, ‘How is this ever going to get done?’”

A major turning point, Ritman says, was when they brought in Peter Barhydt, who in turn recruited Ed Dadakis and Gervais Hearn, and then led the re-launching of the memorial effort. Barhydt, according to Peter Tesei, “has an uncanny ability to develop wide-ranging community support and exemplifies a positive can-do attitude. He is able to bring together varied perspectives and produce consensus.”

Dadakis initially had his doubts. “I’d been aware of the project for a year or so, and I thought it was a wonderful idea,” says the longtime RTM member. “But it didn’t seem to be moving anywhere.” Barhydt convinced him. Determined to see the memorial realized, Dadakis then joined its committee in a largely behind-the-scenes role. “So many people in Greenwich died or knew people who died,” he says, noting that no other town in Connecticut suffered greater losses on 9/11. “This would be a centrally located place where we all could reflect on that horrible day, or rededicate ourselves to never forgetting.”

After being initially brought on by Barhydt, Hearn recalls the early hesitance of larger donors, who were apt to say, “Yeah, but is it going to get built?” The team would convince them that it would be. Other people simply didn’t know anything about the project—or the even new Cos Cob Park—and still others seemed to have succumbed to memorial fatigue. But event by event, Hearn says, story by story, meeting by meeting our team began to convince them, and the project received donations from $1 to $50,000. “And these ripples of water kept going.”

According to Barhydt, the final push came last December with a benefit concert featuring the immensely popular roots band Dispatch, of which Greenwich’s Pete Francis Heimbold is a member, raised $75,000 at Garcia’s at the Capitol Theatre in Port Chester. Also on the bill were two Greenwich natives: singer-songwriter Caroline Jones and Ian Murray, who heads an eponymous indie rock band. Ian and his brother Shep, founders of Vineyard Vines, also designed a special commemorative tie and scarf to raise money for the cause.

According to Barhydt, the final push came last December with a benefit concert featuring the immensely popular roots band Dispatch, of which Greenwich’s Pete Francis Heimbold is a member, raised $75,000 at Garcia’s at the Capitol Theatre in Port Chester. Also on the bill were two Greenwich natives: singer-songwriter Caroline Jones and Ian Murray, who heads an eponymous indie rock band. Ian and his brother Shep, founders of Vineyard Vines, also designed a special commemorative tie and scarf to raise money for the cause.

Finding the right site for the memorial proved to be tricky. Proposed locations included the end of Steamboat Road, Roger Sherman Baldwin Park, Grass Island, Byram Park, and Tod’s Point. Grass Island was the early favorite, since it was on the water, allowed a measure of privacy, and required no beach pass—but there was opposition. Roger Sherman Baldwin Park was the next best choice, but Hilton was less than thrilled. “Although it’s a nice place, it’s right on I-95, the traffic noise is whizzing by, and there’s lots of other sculptures and memorials there. It felt crowded.”

Nobody else thought it was ideal, either, and the project drifted to a halt. Then in late 2012 at a Rotary Club luncheon, Joe Benoit, a former fire marshal in town, made a suggestion to Hilton. “You know, there’s that new Cos Cob Park they’re doing,” he said. “Why don’t you put it over there?”

“So I drove over right after lunch,” Hilton says. “It was a construction site—they were cleaning up the fly ash and other stuff. I think they were at the end of the first phase of the remediation, burying all this fly ash. There were humongous trucks going in and out. I mean, it looked like a strip-mining site. But when I got out to the waterside, I was like, ‘Wow. This would be fabulous.’”

A host of approval hearings lay in wait, but Barhydt worked well with First Selectman Peter Tesei and Parks and Recreation Director Joe Siciliano—among many other advocates—who nimbly helped shepherd the project past the briars.

Hilton, meanwhile, had approached landscape designers Kathryn Herman and Cheryl Brown of Doyle Herman Design Associates in Greenwich. Once the approvals for Cos Cob Park were secured, Herman and Brown devised a multi-layered scheme for the knoll surrounding the glass towers. There would be pin oaks, kousa dogwoods, and bayberry bushes arranged to shelter the memorial site from the parking lot and the homely power station nearby, and to orient visitors toward the water. In time, the knoll would be covered with blonde meadow grass, too, with the walkways winding through it.

Brown says, “In the meadow, there will be flowering perennials that predominantly come up in the fall—so it will be at its best in September.” “That’s one of the great things—landscaping only gets better with time” when plantings settle into their maturity, says Herman. (She credits Roberto Fernandez Landscaping of Greenwich with implementing their vision.) Chuck Hilton adds, “In two or three years it will be so beautiful. You can almost imagine this Wizard of Oz scene you’re walking through, and as you come up the path you’ll see glimpses of the towers.”

That vision is about two-thirds realized—waiting only for the trees to grow taller and the meadow grass to come in. As it is, this memorial is not an object, like so many memorials of old, but a living place. It changes with the light and the weather and the wind. “The other morning I was there when it was still foggy out on the water, and it almost kind of slipped into the fog,” Hilton says. “When it’s bright sunlight there’s a different feel. Jimmy Ritman was there recently when the sun was setting, and he was catching the reflection of the orange light kind of bouncing through the glass. So the glass picks up the color of the environment.”

Who will come?

The memorial was conceived as a serene place where loved ones could reflect and take comfort. But that is only part of the purpose. As one father told Ritman, “I don’t need this memorial to remember my son. I remember him every day. What I want is for other people to remember.” The many people behind the new memorial (including family members like Sally Maloney Duval, who lost her brother Teddy, and Jonathan Egan, who lost his father and aunt, Michael and Christine Egan, respectively) are especially keen to have students visit in order to better grasp the events of 9/11.

“The younger people, all they know is that a building collapsed,” Ralph Sabbag observes. “That’s about it. But there is much more to it. This is a part of American history now.” Susan Wohlforth says, “I love that school children will be brought here. I really hope that that does happen. I think seeing this would give them a whole context of understanding.”

Looking out at the water, she says, “You might remember 9/11 anywhere. But when you really want to reflect, to remember the tragedy, but in a peaceful way, it’s here.” She breaks off. “I’m going to start to cry. I didn’t expect to get emotional. I’m just so happy that it’s here. I really am. Yes, it’s about time. But I am very grateful to everyone who made it happen.”

Susan rises from the bench. She chats briefly with Fred Durante, who has come to inspect the stonework on the terrace, and then she heads down the path. Four people are headed up at the same time—as it happens, Chuck Hilton, his wife, son, and daughter. Hilton smiles a little shyly, as if in anticipation. “I knew it would be beautiful,” Susan tells him. “But it’s even more beautiful than I expected.”